Tourism, nightlife and new businesses have returned around Mogadishu’s Lido Beach and throughout the city. But one Friday night in August 2024, as music blared and hundreds relaxed along the beach, a suicide bomber detonated his vest. Several gun-wielding extremists opened fire on the crowd.

“On the streets nearby, people were fleeing an all-too-familiar threat,” said a report from Channel 4 News. “Al-Qaida-affiliated al-Shabaab said they carried out this attack, as they have so many others over nearly two decades. Somali police said three of the attackers were killed along with the suicide bomber and one taken into custody. A Soldier also was killed in the gun battle.”

When it was over, 37 people had been killed and 212 injured. It was the deadliest al-Shabaab attack since two vehicle bombs killed 121 people and injured 333 in October 2022.

The attacks are a reminder that despite years of foreign military intervention and capacity building, al-Shabaab can emerge from the shadows and inflict significant damage.

AL-SHABAAB FLEXES POWER

Samira Gaid, senior Horn of Africa analyst at the consultancy Balqiis Insights in Nairobi, told Deutsche Welle that the August 2024 attack was al-Shabaab’s way of “reannouncing their return to the city, reannouncing their existence.”

The group, which formed in 2006 as a nationalist movement in response to an Ethiopian invasion, eventually evolved into a terrorist insurgency and al-Qaida’s East Africa affiliate. AU forces pushed the group out of Mogadishu in 2011, so it focused on high-profile terror attacks and on ambushing security forces.

Al-Shabaab extorts taxes throughout the countryside, making the group al-Qaida’s most profitable affiliate. “Their governance model is not just the taxes, but they do have schools where they indoctrinate students from a very young age,” Gaid said. “But the most important thing is how they are able to take into account the grievances that exist within Somali society that led to the state collapse 30 years ago.”

Al-Shabaab also is the largest and strongest al-Qaida affiliate with between 7,000 and 12,000 fighters.

In 2007, the AU Mission in Somalia (AMISOM) deployed to protect and defend the country’s nascent institutions from al-Shabaab while also helping the Somali National Army and police forces handle security. AMISOM gave way to the AU Transition Mission in Somalia (ATMIS) in April 2022. It ended in December 2024.

After Somali authorities requested a delay in the ATMIS drawdown, the AU Peace and Security Council approved the AU Support and Stabilisation Mission in Somalia (AUSSOM). It focuses on post-conflict reconstruction, development and peacebuilding, the council stated. The four-year mission started January 1, 2025, and runs through the end of 2028.

Multinational and national security forces can help keep al-Shabaab at bay. But authorities will have to address the roots of the terrorist group’s resilience, namely its propaganda and communications expertise, its financial prowess, and its use of foreign fighters.

SKILLED MESSENGERS

Al-Shabaab’s extensive communications campaign is a cornerstone of its effectiveness. The group uses social media, radio and a website called Shahada News Agency, its official Arabic-language media outlet.

Shahada in July 2024 indicated that it would publish reports that include all Islamic countries, not just Somalia and East Africa, to show “the acceleration and intertwining of events and the universality of the conflict,” according to the Middle East Media Research Institute. The same day, the propaganda arm launched X and Facebook accounts.

The Somali government works to blunt the proliferation and effectiveness of al-Shabaab’s propaganda. In October 2022, the government officially prohibited “dissemination of extremism ideology messages both from official media broadcasts and social media,” according to a news release. It further noted that it had suspended more than 40 social media pages. Somalia’s National Intelligence and Security Agency has monitored platforms and informed tech companies so they could remove the content.

“It was a difficult task when we started, it needed knowledge, skills and a lot of work,” Deputy Information Minister Abdirahman Yusuf al-Adala told Voice of America (VOA) in March 2024. “We trained people with the necessary skills, special offices have been set up, equipment has been made available, and legislation has been passed by the parliament. More than a year later, we are in a good position, we believe we have achieved many of our targets.”

The government said it had shut down 20 WhatsApp groups and 16 websites believed to be affiliated with al-Shabaab. Even so, the extremists constantly create new social media accounts and adjust domain names. The group also breaks through by virtue of the volume of material it produces and disseminates.

“In any given week, around 20 to 25% of the content we find on the internet has likely been created by al-Shabab,” Adam Hadley, executive director of the London-based Tech Against Terrorism, told VOA. “It’s essentially the largest single producer of terrorist material on the internet.”

FINANCIAL PROWESS

Al-Shabaab is notorious for the wealth it generates through illicit trade, extortion and taxation. Some estimate its yearly intake at up to $150 million. Most money comes from taxing civilians, farmers and businesses. Other funding comes from road tolls and trading charcoal, sugar and fishing, according to The Africa Report. The extremists back the revenue flows with threats of violence.

Government authorities have closed down hundreds of accounts, and western allies have targeted money laundering networks in East Africa, Europe and the Middle East. But al-Shabaab front companies have bought interests in some banks and demand that officials release frozen money.

“Banks have frozen the money in the banking accounts, but banks are allowing them to take out money more easily as they don’t want them to leave the bank,” Matt Bryden, a Canadian political analyst and former worker for United Nations organizations in the region, told The Africa Report. “They have talked to the leader of the bank, and he doesn’t want to lose his business. They are putting pressure on bank managers to release the funds.”

FOREIGN FIGHTERS

Ironically, an extremist group that formed in reaction to an incursion of foreign forces now reportedly relies on East African fighters to boost its own ranks. Al-Shabaab has been producing messages in Swahili since at least 2010 to attract recruits, according to the Combating Terrorism Center at West Point in New York.

A confidential AU assessment claimed that as ATMIS continued its drawdown, al-Shabaab “created a pan-East African force” with fighters from Burundi, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Ethiopia, Kenya, Rwanda, Tanzania and Uganda, according to a June 2024 report in The EastAfrican newspaper.

Many of these fighters come from Kenya, which has a significant Somali population and a number of disaffected Muslim citizens eager to improve their economic standing. Three from Nairobi’s Pumwani slum spoke to PBS in 2016. One man, using the pseudonym Abdul, said Kenyans who had fought with al-Shabaab radicalized him in prison.

“They started talking, how their business was good,” Abdul told PBS. “Their business was al-Shabaab.” He got $500 to join and $100 a week after that.

Robert Ochola worked at the grassroots level to counter radical teaching. “It’s a battle,” he told PBS. “It’s a battle of hearts and minds, and it depends on who will offer these people you are fighting for more.

“When you have nothing, you don’t have anything to lose. When you’ve dropped out of school, probably in primary school, you know, your mind is somehow, it’s closed in a box. And then in comes somebody who feeds and fills up your mind with some radical things.”

SOMALIA’S WAY FORWARD

Despite the ebbs and flows of the battle against al-Shabaab, Somalia and its international partners continue to score meaningful victories. In October 2024, the Somali National Army and local forces conducted an operation in the Mudug region’s Qeycad area in which 30 militants were killed, according to news website HornLife.com. Two commanders, Mohamed Bashir Muse and Madey Fodey, were captured, according to reports. Forty al-Shabaab fighters also were wounded in the two-day battle.

Somali Soldiers conducted the operation with help from Galmudug State forces and local clan militias. Many gains against al-Shabaab have come through leveraging clans’ discontent with the extremists. This has worked especially well in the central part of the country, according to a 2023 International Crisis Group report. Al-Shabaab alienated many communities with its “persistent, onerous demands for money and recruits” and with the violence it dispenses for refusing to comply.

Somali Soldiers have provided clan militias ammunition, food and medical evacuations, and the volunteer fighters, known as macawisley for the sarongs they wear, help Soldiers navigate the local terrain and its people. This, combined with ATMIS support, U.S. airstrikes and other foreign assistance, has been a force multiplier against extremists.

However, not all clans have been as helpful, and al-Shabaab has demonstrated an ability to inflict damage through suicide car bombs and other tactics in areas it has lost, the Crisis Group reports. The group also has adapted its approach to local populations by “offering more carrots than sticks” and weaving a commitment to the public good into its rhetoric.

“The federal government’s collaboration with the macawisley likely prompted Al-Shabaab’s shift in tone,” according to the Crisis Group. “In the past, the group has been more willing to offer concessions to clans when it feels weak, only to roll them back later when it is in a stronger position.”

The challenge for Somalia’s government is to find a way to hold on to liberated areas. When government forces, aided by clan-based militias, drive extremists from an area, they risk losing gains without a plan to maintain a presence while also fulfilling service commitments, according to the Crisis Group. Failing to do so gives al-Shabaab an opportunity to return.

AUSSOM started its work in January 2025. Rosalind Nyawira, a Kenyan security expert and former director of Kenya’s National Counter Terrorism Centre, said it’s good that a new mission is in place to fill security gaps.

“We will have to wait and assess any success because the enemy they’ll be dealing with also has a way of adjusting — adjusting to security deployments, adjusting to strategies,” Nyawira told the Combating Terrorism Center at West Point in September 2024. “The good thing is that, at least when there’s another mission taking over, there isn’t a vacuum; any vacuum would give terrorists more space to operate. Hopefully, with a good strategy, they can hold ground and be successful. We all hope that it will work well.”

VIOLENCE IN SOMALIA

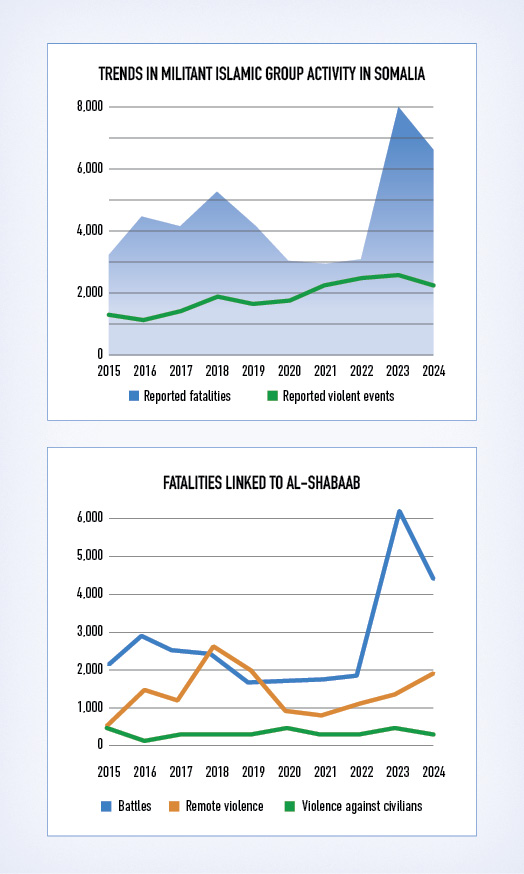

Somalia accounts for about a third of militant Islamist-related deaths in Africa, second only to the Sahel.

The 6,590 reported deaths in 2024 are more than twice the 2020 total.

This increase in fatalities is due in large part to a government offensive launched in 2022 and al-Shabaab counterattacks. These battles have diminished over the past year.

Virtually all reported events and fatalities are linked to al-Shabaab. The Islamic State in Somalia accounts for less than 1% of this activity in Somalia and Kenya.

Drones and suicide bombings, which constitute “remote violence,” have increased in recent years. There were 640 incidents in a one-year span. Fatalities linked to al-Shabaab’s use of remote violence have more than doubled since 2020 to 1,950.

Source: Africa Center for Strategic Studies using data from the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (years ending June 30