Ghana is known for its history of strong civilian government, adherence to democratic principles, and international engagement regionally and around the world. It serves as an island of stability in West Africa, a region beset by military coups and violent extremism.

It is not, however, immune from some of the stressors faced by its neighbors, especially regarding disinformation. Malign influencers have used no fewer than 72 campaigns to obfuscate, twist and distort reality in West Africa, according to a March 2024 Africa Center for Strategic Studies (ACSS) report. Ghana is the victim of at least five of these efforts perpetrated by China, Russia, domestic political actors and others.

“With the advancement of media, now there’s a multiplicity of channels all over the country, and we’re very proud of that,” Ghana’s then-Minister for Information Kojo Oppong Nkrumah told Nigeria-based FactCheckHub in late 2023. “The risk, therefore, is that information that lacks integrity finds itself in the public domain, and that’s what gives rise to mis/disinformation.”

Harriet Ofori, who tracks disinformation as research and project manager at Penplusbytes, a Ghanaian not-for-profit, said her organization works with the media, academic institutions, UNESCO, the National Commission for Civic Education and others on a wide range of projects and initiatives. She recalls one particularly dangerous disinformation campaign.

“In July 2023, an audio message calling for attacks on the Ghanaian government over the forced repatriation of Fulani asylum-seekers spread via WhatsApp in northern Ghana,” she told ADF via email. “The message falsely claimed the government was trying to exterminate the Fulani population and urged retaliation. This message was distributed by a media wing of Jama’at Nusrat al-Islam wal-Muslimin (JNIM).”

As disinformation increases at an almost exponential rate from violent extremist organizations, Russian lackies and Chinese interests, some African nations are intensifying their efforts to push the continent toward the truth. It’s a herculean task that requires extraordinary detection mechanisms, early warning systems and strong collaboration between civil society groups, governments, the media and security forces.

Ghana and its neighbor, Côte d’Ivoire, stand out in this regard. Ghana in December 2023 conceived a draft National Action Plan to tackle disinformation. It came after a National Conference on Disinformation and Misinformation and is the work of political parties, civil society groups, the media and development partners, FactCheckHub reported. When approved, the action plan seeks to protect information integrity, push media literacy and cultivate responsible digital citizenship.

Penplusbytes also has collaborated with the Ghanaian government. It conducted disinformation research with support from the National Endowment for Democracy and then engaged officials, including the Ministry of Information, to share research findings and discuss recommendations for combating disinformation as the nation works on its action plan, Ofori said.

To Ghana’s west, Côte d’Ivoire is making the public aware of disinformation’s dangers. Amadou Coulibaly, minister of communication and digital economy, told residents of Abidjan’s Adjamé community in July 2024 that when they share false information on social media, it makes them “digital wizards,” according to the Ivoirian news website Koaci.com. His speech was part of the nation’s #EnLigneTousResponsables (Online All Responsible) campaign.

A NEW TOOL EMERGES

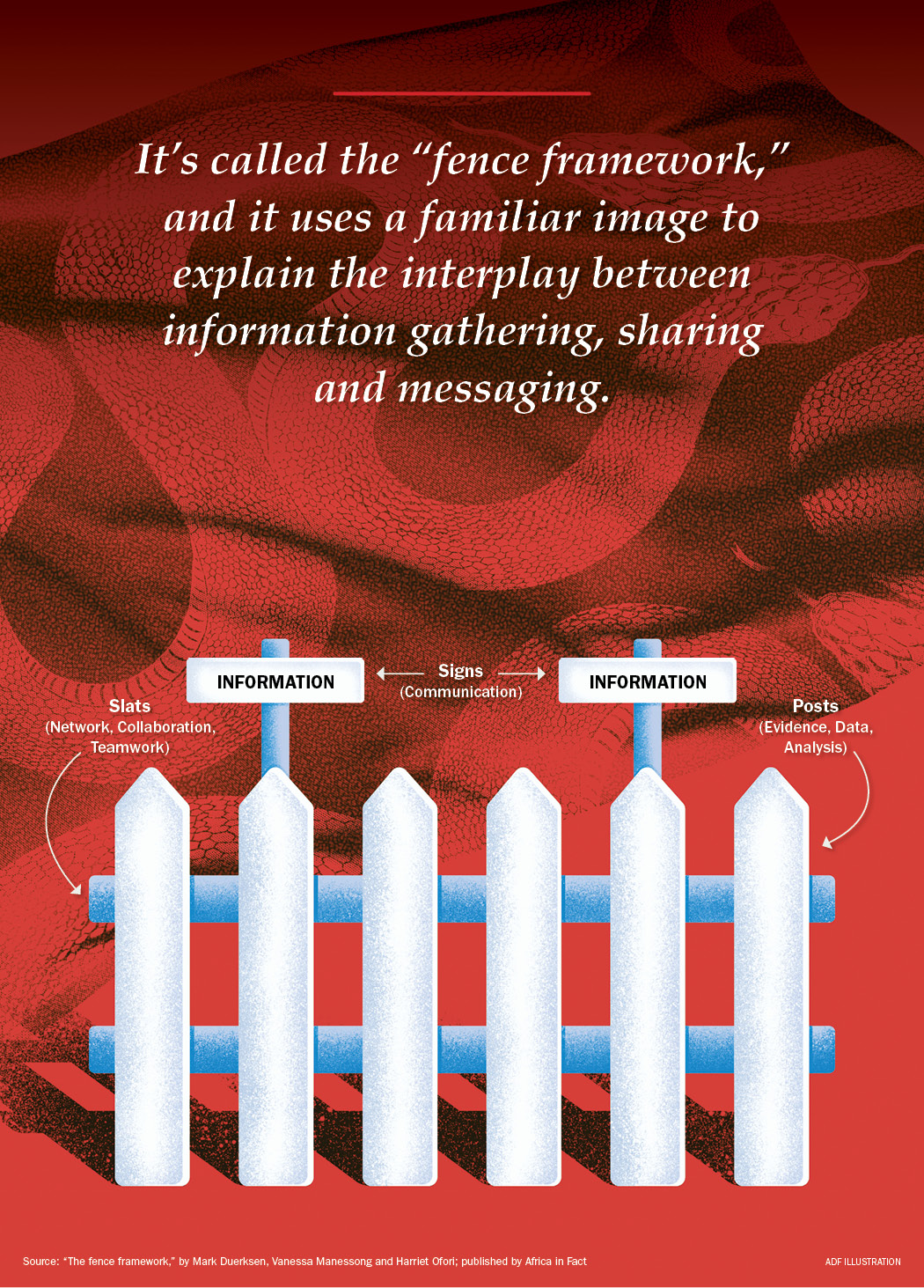

As disinformation continues to grow, a new process aims to detect the threat and turn the tide against it in Africa’s communications landscape. It’s called the “fence framework,” and it uses a familiar image to explain the interplay between information gathering, sharing and messaging.

The “challenge is to create surge protectors — what we can simply call ‘fences’ — to keep disinformation out and empower online users to protect themselves from manipulative interference,” wrote Dr. Mark Duerksen, research associate with the ACSS; Vanessa Manessong, an investigative data analyst at Code for Africa in Cameroon; and Ofori. The three published their paper, “The fence framework,” on the website Africa in Fact in July 2024.

The fence motif, which depicts posts, slats and signs, illustrates how to address disinformation in a coordinated way. When the three elements work together, responders can identify, classify and respond to disinformation efficiently.

POSTS: THE DATA

In the fence illustration, the posts form the foundation of the response. They represent the data responders have about disinformation. The ABCDE framework asks a series of crucial questions at this stage: What actors are involved? What behavior is exhibited? What kind of content is being distributed? What is the degree of the distribution, and what audiences are targeted? What is the overall effect of the disinformation?

Academics, journalists, fact checkers, nongovernmental organizations, various civil society groups and security forces can collect this type of data. The collection offers insights about which campaigns are going viral or doing the most immediate damage in the information environment. What particular narratives are being spread? Are perpetrators using simple cut-and-paste techniques on social media, or more sophisticated techniques? All of this information comes together to form a picture that is useful in the second element of the framework.

SLATS: COOPERATION

Slats connect the posts and hold them together. The slats represent the cooperation that helps people share and make sense of the data they gathered about the disinformation being spread.

“Research on disinformation campaigns must be exchangeable and interpretable by practitioners to have an impact,” the article states. Doing so relies on established standards, shared terminology, networks and collaboration so information can be reliably shared among the people and agencies who need to see it.

Shared terminology, understanding and approaches will let an NGO in one country communicate with a media fact-checking organization in another about threats it is seeing. The hope is that through this process, a bigger picture will emerge about the nature of the disinformation campaign and who is spreading it. Because disinformation transcends national borders, this type of collaboration is essential.

One useful collaboration tool is an information sharing and analysis center (ISAC). The vision is to have a network of ISACs set up across the continent to serve as hubs for analyzing and countering disinformation. As of mid-2024, there were no ISACs in Africa, but

Debunk.org, an independent Lithuanian anti-disinformation think tank, has funding to set up an ISAC in Kinshasa, Democratic Republic of the Congo.

SIGNS: RESPONSE

Once data is collected, organized, analyzed and shared, an appropriate response can begin. This is the signs component of the fence framework. The data and relationships have to work “toward an end, whether that’s doing an awareness-building campaign where you’re just trying to get the word out about what’s happening, whether it’s lobbying some of the social media platforms, telling them what’s happening, trying to work with them to take down certain content or to block or take down some of these bot networks,” Duerksen told ADF.

This is the stage at which officials warn the public about active disinformation campaigns. This can include countering bad information with good messaging or telling information platforms that hostile forces are using them to spread disinformation. This kind of communication and capacity building also can come before disinformation is released.

“Your response is trying to build digital literacy in society, kind of helping people understand that these attacks are coming,” Duerksen said. Doing so in advance of an attack sometimes can preempt disinformation.

THE ROLE OF SECURITY FORCES

When fighting disinformation, cooperation among a range of agencies and interests is essential. Militaries have a part to play. Disinformation is a legitimate concern in the security arena because it constitutes a form of hybrid warfare and can pose a real, tangible threat to Soldiers, including peacekeepers, who operate in areas teeming with toxic messaging. Such was the case with the United Nations peacekeeping mission in the DRC.

In that mission, disinformation and misinformation were a constant threat, and one that prompted leaders to build what they called a “digital army” to fight the problem. Through the strategy, the mission empowered civilians, particularly young ones, to detect malign news and social media posts and respond with accurate information.

Bintou Keita, United Nations special representative for the DRC and head of the U.N. peacekeeping mission there, said in a 2023 interview with UN News that armed groups deliberately spread lies to incite people to oppose the mission.

“Just to give you one example, while the high level segment of the General Assembly was going on, I was in Kinshasa when somebody decided to create fake news which was a photo of me from I think three years ago, when I was the assistant secretary-general for Africa [at the U.N. headquarters], in New York and had the text which was saying basically that I, as the head of [the mission], was resisting the departure of the mission,” Kieta told UN News. “This is untrue because, first of all, I was not here at the General Assembly. I was in Kinshasa.

“We had a discussion on what do we do, do we say that this is fake? What do we do at the end? I think the colleagues decided, OK, it is fake, and it went.”

Military and security forces often have more assets and technical expertise than their civilian partners, but they must take care when operating in the public information environment. In fact, there are good reasons why the military should not lead these efforts at all.

Sometimes, citizens don’t trust their nations’ military forces. If those forces then start telling people what information is good and what isn’t, it can breed skepticism. That will undermine genuine attempts to combat disinformation.

That’s why journalists, fact checkers and researchers might make better front-line messengers for civilian populations, especially if they are trusted sources such as local radio broadcasters or reporters.

Still, Duerksen said, military forces need to be aware and keep their “finger on the pulse” of the information environment where they are serving by monitoring local radio and social media. This way they can track false narratives and report back to local journalists and influencers. What they should not do is be perceived to be lobbying public platforms or putting out information themselves.

“So, when you see this stuff, who do you go to?” Duerksen said. “Who do you take it to? Who is the best mouthpiece for it? Who is in the best place to respond? And that’s most likely not the military.”

Defining Terms

DISINFORMATION is false and manufactured to deliberately harm people, social groups, organizations or a country. An example is spreading a false rumor that security forces are supplying weapons to terrorists.

MISINFORMATION also is false, but it lacks a deliberate intent to cause harm. For example, community leaders might unwittingly spread a false claim they believe to be true.

MALINFORMATION, though based in reality, is used to cause harm. It could include leaked information that should have remained private. It also can include hate speech.

Source: “Information Disorder: Toward an interdisciplinary framework for research and policy making,” 2017, by Claire Wardle, Ph.D., and Hossein Derakhshan

The Dangers of Deepfakes

As artificial intelligence (AI) technology continues to grow, African officials will have to be on the lookout for a particularly insidious disinformation tool: deepfakes.

Deepfakes are a form of digital media created by AI tools that can be used to manipulate photos, audio and video. This can be dangerous because they can be used to create media that purports to show a political or well-known figure saying or doing something they wouldn’t normally say or do.

Disinformation attacks that incorporate deepfakes pose another problem in that certain free, downloadable software applications can make them easy enough for almost anyone to create.

The implications for use by terrorists and violent extremist organizations are dire.

“A future scenario might involve automated bots spreading deepfake videos that incite protests or violence, rapidly disseminating across multiple platforms, each tailored to resonate with specific subgroups,” according to Lidia Bernd’s 2024 article, “AI-Enabled Deception: The New Arena of Counterterrorism,” for Georgetown Security Studies Review.

Governments, tech companies and academic institutions will have to work together to develop and continuously update AI-driven tools to detect deepfakes, Bernd wrote.

South African researcher Layckan Van Gensen, junior lecturer in mercantile law at Stellenbosch University, promotes laws to protect image rights as a way to combat deepfakes. Image rights legislation, she wrote for the Daily Nation newspaper, would clearly define a person’s image, specify when that image has been infringed and provide the image holder legal remedies for unauthorized use.