Roadblocks to Respectability

Structures and Behaviors Can Keep Security Forces From Effectively Serving Their Nations

ADF STAFF

For a nation’s military to be ethical and effective, it must adhere to certain objective standards. Chief among those is its willingness to be subjected to civilian rule.

That has not always been the case with African nations since the era of independence began, and some countries still struggle to meet that basic, but vital, standard.

Émile Ouédraogo, a retired colonel in Burkina Faso’s Army and an adjunct professor of practice at the Africa Center for Strategic Studies, lists four major obstacles in his paper, “Advancing Military Professionalism in Africa.”

The obstacles are colonial legacies, ethnic and tribal biases, a politicized military and militarized politics, and a lack of operational capacity or mission. Here is a brief look at each.

THE LEGACY OF COLONIALISM

Colonial powers inevitably structured their colonies to benefit their administration of government to secure that regime and to manage populations in a way that preserved central authority.

Everything from the location of national capitals to the demarcation of borders served colonial interests. Likewise, militaries in colonies had to ensure security while avoiding the prospects of rebellion. West African militaries “mostly emerged from the colonial armies that were created for the purposes of political expediencies to quell indigenous resistance and serve the geo-strategic interests of colonial powers,” Naila Salihu, program and research officer with the Kofi Annan International Peacekeeping Training Centre, wrote in a report for ACCORD.

In West Africa, ethnic minorities from the north of countries such as Ghana, Nigeria and Togo were used to compose colonial militaries, Ouédraogo wrote. Doing so helped colonial powers “counterbalance historically more powerful ethnicities” concentrated in southern regions.

Simply put, colonial powers had no interest in building long-lasting security institutions that would promote fairness, healthy civil-military relations and good governance outside of colonial aims. Indeed, Salihu writes, British and French colonial authorities did the exact opposite, even as their own governments were strengthening their democratic institutions back home. Despite this, some nations emerged from colonial rule with the ability to establish healthy security institutions.

“It is noteworthy that countries like Senegal, which were able to reorganise their military and institutionalise their civil-military relations, were able to sustain civil rule,” Salihu wrote. “Other countries, such as Ghana, were unable to do so and became enmeshed in a cycle of coups and countercoups in the first three decades of independence.”

ETHNIC AND TRIBAL BIASES

This obstacle is apparent in regimes in which the president forms a military primarily composed of members of his own ethnicity or tribe.

The practice is known as “ethnic stacking,” and it can have dire consequences for a nation, even as it bolsters autocratic leaders.

“Since decolonization, worried by the possibilities of coup attempts and ethnic insurgencies, many leaders have continued to rely on the recruitment and promotion of coethnics to control the military and ensure its loyalty,” Kristen Harkness wrote in the paper, “The Ethnic Stacking in Africa Dataset: When leaders use ascriptive identity to build military loyalty.”

Stacking can prevent coups and strengthen regimes in the short term, but excluding certain groups also can lead to widespread unrest that results in riots, insurgencies and ethnic rebellions, according to Harkness. Military members serving in such a system “behave differently toward protestors and rebels hailing from out-groups, shaping human rights practices, surveillance, repression, and other repertoires of state violence,” Harkness wrote.

Unfair promotion practices in an ethnically stacked military can undermine combat effectiveness. When the military is diverse and reflects the country it serves, it tends to be more effective.

“A military composed of troops from communities across the country, on the other hand, can create a strong foundation upon which a democratic state can be built,” Ouédraogo wrote. “A diversified force also creates conditions favorable to the professionalization of the armed forces as advancements are more likely to be merit- rather than ethnic-based, and allegiance would be to the nation as a whole rather than to a particular ethnicity.”

POLITICIZED MILITARIES

This phenomenon arises when leaders rely on

security forces instead of the civilian population for support. Sometimes, certain elements of the national security apparatus can become so favored by rulers or ruling parties that they receive more funding, equipment and training than other subgroups within the armed forces.

The precariousness of this practice was demonstrated in Côte d’Ivoire starting in 1960 when Félix Houphouët-Boigny, the nation’s first president, began his 33 years in power. He reduced the military’s size and formed a militia loyal to his party composed mostly of personnel from his own ethnic group. His manipulation, Ouédraogo wrote, resulted in some officers receiving higher pay than other civil servants, positions in the party and other perks, paving the way for future instability that would result in catastrophe.

When Houphouët-Boigny died in 1993, Henri Konan Bédié took power “with the help of a few officers of the gendarmerie belonging to his tribe,” an unprecedented act that positioned the same group to help place Laurent Gbagbo in power in 2000.

However, years later in Tunisia under the rule of President Zine El Abidine Ben Ali, the same dynamic appears to have produced a contrary result. During the 2011 Arab Spring rebellion, the nation’s 40,000-strong uniformed Armed Forces was disconnected from the Ben Ali regime, which instead favored the national police force and the presidential and national guards. When civilian protesters took to the streets, Soldiers and their commanders refused to stand between protesters and Ben Ali. He fled the country, and a long, complicated and fragile move toward democracy commenced.

LACK OF MISSION, OPERATIONAL CAPACITY

Professional militaries are educated, well trained, sufficiently equipped, and have clear guidance about their mission and purpose. Mission readiness depends largely on healthy command-and-control structures and civil-military relations.

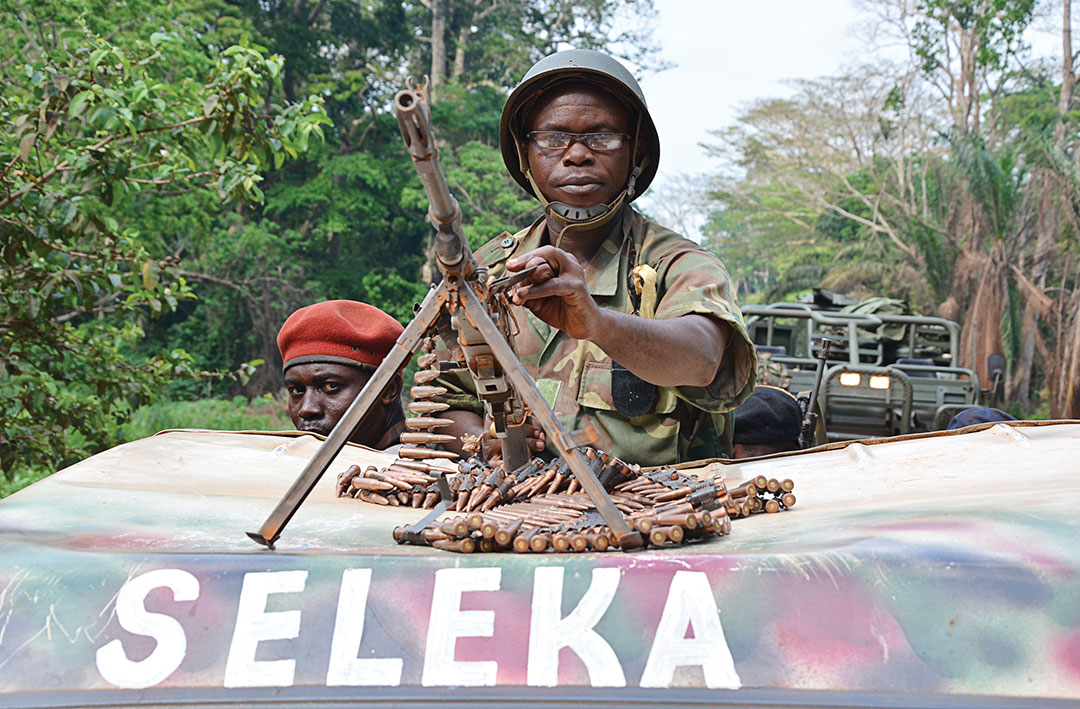

As examples, Ouédraogo points to the swift collapse of Mali’s security forces when attacked by Islamist extremists in 2012 and the ease with which Seleka rebel forces took the capital, Bangui, in the Central African Republic a year later. Potential explanations for such failures are command chain gaps that lead to lack of discipline, lack of procurement oversight, low morale and “a misaligned or obsolete mission.”

Command chain gaps can lead to rank-and-file recruits indulging in crimes that go unpunished, leaving the impression that Soldiers are above the law, Ouédraogo wrote. For example, in Gbagbo’s Côte d’Ivoire in 2000, servicemen loyal to Gbagbo killed civilians who contested his election. They were not held accountable.

African militaries also have been known for being top-heavy in their leadership. Ouédraogo points out that before 2012, Mali’s army had one general for every 400 Soldiers, whereas a typical NATO infantry brigade consists of approximately 3,200 to 5,500 troops and is commonly commanded by just one brigadier general or senior colonel. This “officer inflation” can strain budgets and frustrate those who perceive a lack of merit in promotion, leading to a lack of discipline and low morale.

Militaries typically are formed to protect against foreign threats, yet that is not the profile of most African conflicts. African militaries are more likely to face internal threats, such as the extremist insurgencies in Mali, northern Mozambique, northern Nigeria and Somalia, for example.

“The West has this model of a disciplined, neutral army that stands on the sidelines, independent of domestic politics,” Jakkie Cilliers, founder and board member of the Institute for Security Studies, told Foreign Policy. “But the African model is of a military that is used internally and is part and parcel of domestic politics and resource allocation.”

These domestic insurgencies draw attention to the disconnect between a military’s mandate and the most prevalent threats, Ouédraogo wrote.

“African security forces, therefore, must become demonstrably more competent and professional in order to prevail,” he wrote. “Until African leaders identify a clear mission for their security institutions and incorporate this into their strategic planning processes, they will be unable to resource and train their troops for the real security challenges they face.”

Comments are closed.