REUTERS

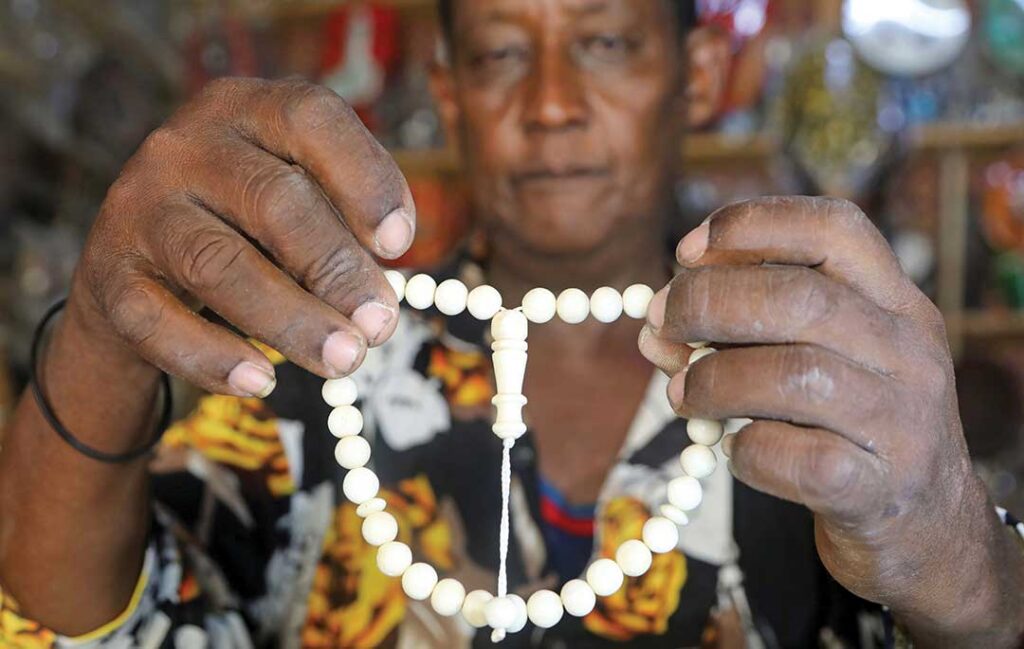

Somali artisan Muse Mohamud Olosow carefully sorts through a huge pile of camel bones discarded by a slaughterhouse in Mogadishu, selecting pieces that he will carve into jewelry and ornate beads used by fellow Muslims while reciting prayers.

To Olosow’s knowledge, he is one of just four artisans in his country of 16 million people who work with camel bones. In 1978, in one of Somalia’s many periods of war and turmoil, gunmen killed dozens of craftsmen in Mogadishu and another town, he said.

For years, he carved his bones secretly at home and then took them to markets to sell discreetly.

Olosow, whose strong hands and arms bear callouses and muscles from his work, learned his craft from his father in 1976.

He plans to ensure that this decades-old tradition does not fade away after he is gone.

“My kids will inherit these skills from me, that I inherited from my father,” he said from his workshop in the Somali capital. “I do not want these skills to stop.”

His clients mostly are government officials or wealthy Somalis living abroad. Just one set of his painstakingly carved prayer beads can cost about $50 in a country where seven in 10 people live on less than $2 per day.

A customer visiting his shop says the work justifies the price. “What matters is quality not price. I prefer this one to beads imported from other countries like China.”

For Olosow and his family, carving bones has been their main source of income for decades. They invested nearly $5,000 to import machines from Italy to chisel and puncture the tough bones, he said, making it faster and safer to work “without bruises.”

“Our plan is to export these items to other countries,” he said. “We shall continue this art craft until we become rich! God willing.”