ADF STAFF

When Sierra Leonean fishermen board their small wooden boats and head out into the open sea to make a living, sometimes they can see their enemy.

Along the ocean horizon float larger fishing vessels and trawlers — virtually all of them foreign and most Chinese — waiting to scoop up their catch using an array of illegal and destructive methods. Up to 70 trawlers work in Sierra Leonean waters around the clock, according to a BBC report.

Sometimes the rust-stained trawlers drop heavy, metal doors that sink and help drag nets across the ocean floor, scraping away priceless life and habitat. The huge, gaping nets trap sea life indiscriminately, laying waste to the fragile ecosystem as they go.

Sometimes the boats will string nets between them and steam away as “pair trawlers,” again scooping up fish on an industrial scale. The practice is illegal in Sierra Leonean waters. Some crews will lie about the size of their catch (or not report it at all), fly false flags or fish in prohibited areas. Sometimes they will bring their catch ashore to sell, undercutting the thousands of artisanal fishermen who depend on selling fish for their livelihoods.

Other times they will transship their catches to larger reefers, which steam off to foreign ports in China, Russia and elsewhere, leaving Africa’s waters depleted and its local fishermen deprived.

But what if after all their deception and trickery, these illegal fishing vessels couldn’t pull into a port and offload their catch? What if after all their work and scheming there was nowhere to take the fish — and no way to sell it?

PORT STATE MEASURES AGREEMENT

In June 2016 a new global tool in the fight against illegal, unreported and unregulated (IUU) fishing took effect. The United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) Agreement on Port State Measures to Prevent, Deter, and Eliminate Illegal, Unreported, and Unregulated Fishing introduced a simple way to fight IUU fishing — by limiting access to ports.

The Port State Measures Agreement (PSMA), as it is commonly called, is the first binding international pact that targets IUU fishing. Its potential to end the global scourge is promising. It seeks to prevent those who fish illegally from landing their catches at ports, thus keeping ill-gotten seafood from reaching national and international markets.

“The Port State Measures Agreement is probably the most effective way to try to counter illegal, unreported and unregulated fishing, by putting the onus on vessels to essentially verify that any fishing that they are looking to land in a country has been caught legally,” said Dr. Ian Ralby, chief executive officer of I.R. Consilium and an expert on maritime affairs.

The agreement is a major advancement in countering IUU fishing. It deemphasizes the need to pursue, intercept and prosecute those who flout regional, national and international fishing regulations. That model is a tall order even for the richest of nations because of the vastness of the maritime domain. Without a global maritime force, Ralby told ADF, it’s impossible to effectively patrol the world’s seas.

With a port-centered approach, even a country “that doesn’t have a single naval asset” or lacks effective maritime domain awareness can have a potent law enforcement tool for addressing unlawful fishing, Ralby said.

The PSMA offers mechanisms for vetting fishing vessels before they can dock at ports and unload their catches. It also gives boats with a history of compliance and adherence to rules a way to be “fast-tracked” into foreign ports.

In short, those who follow the rules are rewarded. Those who don’t are not.

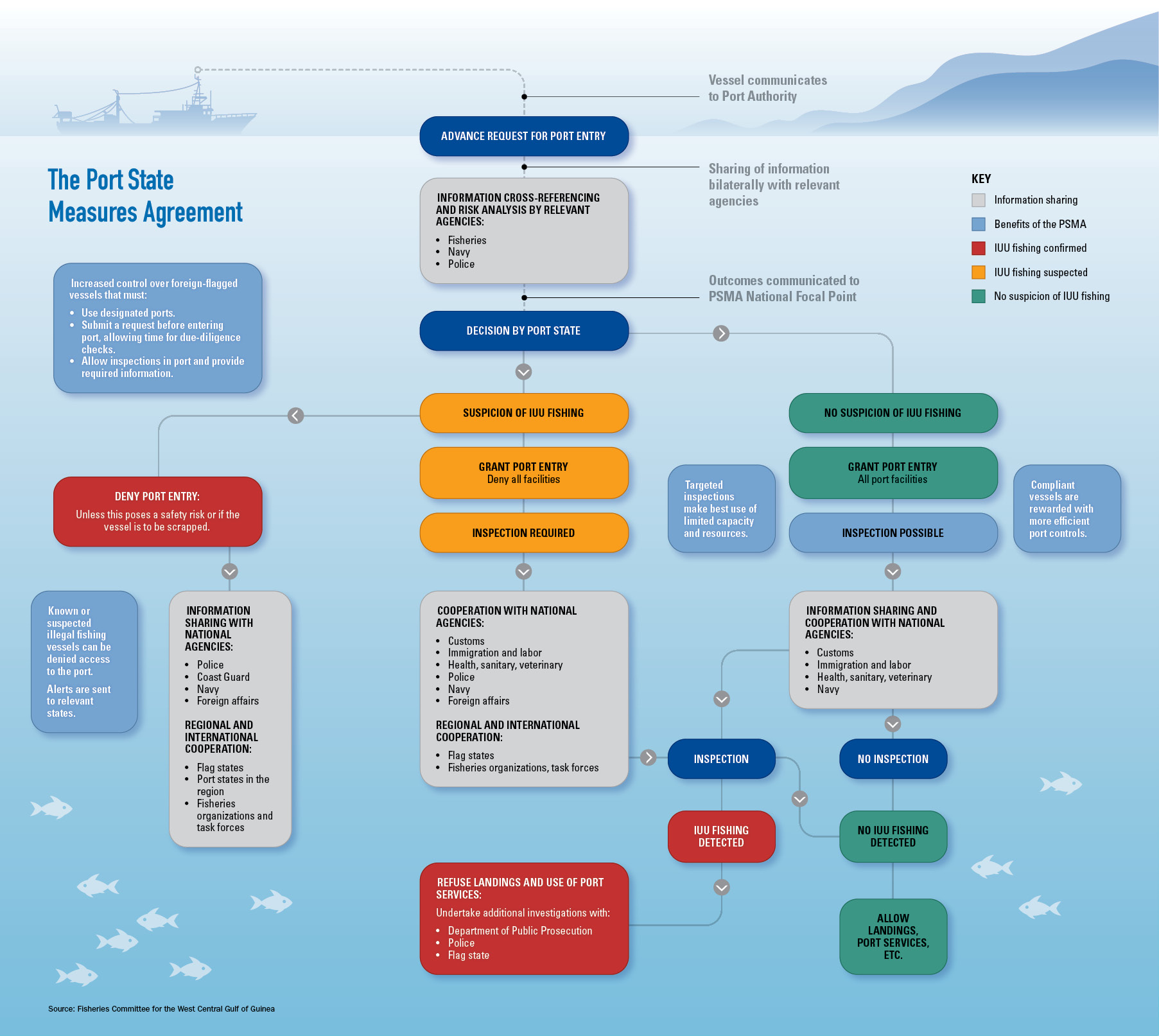

The Fisheries Committee for the West Central Gulf of Guinea (FCWC) explains that authorities lead implementation and operation of the agreement in cooperation with other national agencies to analyze risk, identify high-risk vessels and decide whether to grant port entry to foreign-flagged fishing vessels.

Generally, according to the FCWC, a vessel seeking access to a nation’s port would make an advance request. Information then could be checked, cross-referenced and analyzed by fisheries, port, navy and police authorities. If the port state suspects the vessel has engaged in IUU fishing, it could deny entry or condition entry on an inspection.

If no IUU fishing is suspected, port authorities can grant the vessel access to all facilities, but still may require an inspection. Vessels with a history of compliance can be rewarded with more efficient port controls each time they seek entry. This is the fast-tracking provision of the agreement.

Ralby said he has helped parties think about the interagency cooperation necessary to identify suspect vessels and make the agreement work. The goal is to benchmark indications of illicit behavior through the agreement, which is different from looking for a vessel engaged in IUU fishing on the open water.

“The reality of the matter is fish have to land in order to enter the supply chain, which means in order for the illicit activity of IUU fishing to be profitable, they have to get the fish on land and to market,” Ralby said. “And so if you put a massive roadblock to bar that process from occurring, you take out the reward portion of the equation, and you increase the risk that they’re actually going to get caught.”

ADOPTION IS NOT ENOUGH

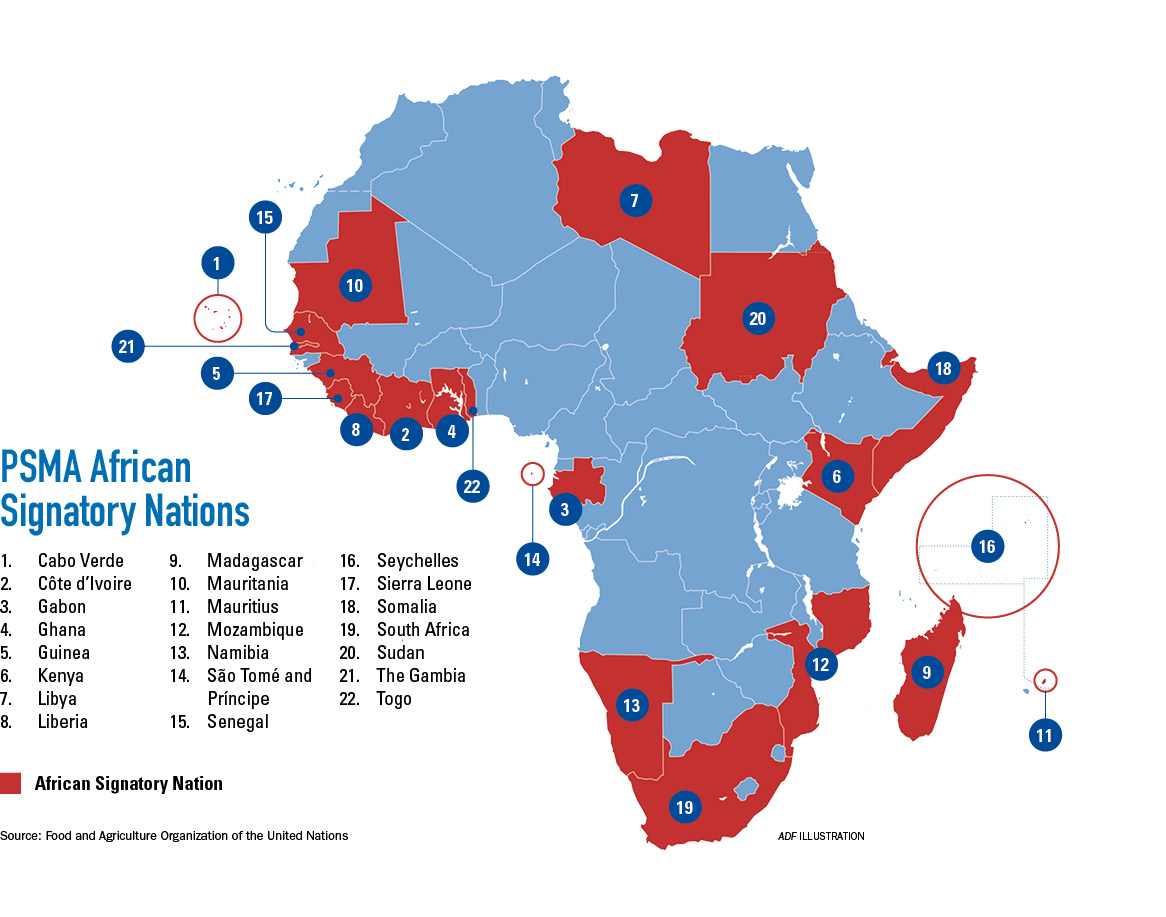

All but 16 of Africa’s 54 nations have coastlines, as do more than 200 other nations and territories. But so far, only 66 nations are parties to the agreement worldwide, and 23 of those nations are in Africa. The various nations are at different stages of acceptance, approval, ratification and accession, according to the FAO.

That is a significant and laudable response, but it’s not enough to make the agreement as effective as it can be. Gaps in the coastlines covered by the agreement give criminals safe havens for landing catches. For example, most of West Africa is a party to the agreement. But Guinea-Bissau is not. So a vessel could avoid one nation, steam up the coast and dock at another to avoid scrutiny and controls.

Gaps in the coastline left by nations that have not yet joined the agreement will produce significant vulnerabilities. But Ralby explained that nations that are parties to the agreement still have tremendous advantages and opportunities through inspections and port controls. Some African nations have some of the highest reliance on fish protein in the world, so having every tool at their disposal to counter IUU fishing will be vital. There is tremendous benefit, he says, whether it’s one, 23 or all 38 African coastal nations operating under the agreement.

Gaps in the coastline left by nations that have not yet joined the agreement will produce significant vulnerabilities. But Ralby explained that nations that are parties to the agreement still have tremendous advantages and opportunities through inspections and port controls. Some African nations have some of the highest reliance on fish protein in the world, so having every tool at their disposal to counter IUU fishing will be vital. There is tremendous benefit, he says, whether it’s one, 23 or all 38 African coastal nations operating under the agreement.

Also, even if every coastal African nation adopts the PSMA, it will not be effective without being implemented “efficiently, effectively, consistently and transparently,” Ralby said. African nations will have to harmonize efforts so that all countries are working from the same set of standards and sharing information. “Any difference in that approach will be exploited,” he said.

The potential for corruption also will have to be addressed. The PSMA only will be as good as the people charged with enforcing it. The international fisheries market has significant value; it exceeded $240 billion in 2017 and is expected to surpass $438 billion by 2026, according to Research and Markets. Ralby said that value can entice some people into corruption such as through bribes to ignore regulations or to sign off on catches when they shouldn’t.

Port states also will have to ensure that compliant vessels that receive fast-track access to ports don’t exploit that privilege by trying to sneak in IUU catches. Ralby suggested constant and random reviews to ensure that fast-tracked vessels stay compliant.

Ralby said as COVID-19 spreads in Africa and elsewhere, combating IUU fishing is likely to present a bigger challenge. The disease has complicated the global supply chain, so opportunities to skirt rules are likely to be explored. Likewise, law enforcement will be more difficult because there’s likely to be less interest in boarding vessels. This could change the face of the problem in the near term.

Even so, African nations are taking steps to familiarize themselves with the elements of the agreement. Just before COVID-19 started spreading in Africa, Sierra Leone held an exercise on the PSMA in Freetown in February 2020.

Representatives from the nation’s fisheries police, health, naval, maritime, port and justice authorities took part during the weeklong capacity-building workshop. The FAO led the event. Sierra Leone ratified the agreement in September 2018.

Participants used the scheduled arrival of a foreign-flagged vessel to discharge its catches in Freetown as an opportunity to participate in a case study and learn about interagency cooperation and the exchange of information, a key element of the agreement.

Sierra Leone’s neighbor Liberia held a similar event about the same time in Monrovia for representatives from the fisheries, maritime, port, health, customs, immigration, coast guard, commerce, justice and agriculture authorities.

The workshop used a foreign-flagged refrigerated cargo vessel unloading fish transshipped from vessels in Guinea-Bissau as a case study for PSMA procedures such as exchanging information and interagency cooperation.

The agreement only will get stronger as more nations sign on, slowly constricting the number of ports that criminals can use to offload and sell ill-gotten fish. According to the Pew Charitable Trusts, “Consistent international momentum over the past few years has boosted the number of parties to the agreement, making it increasingly difficult for illegitimate catch to make its way to national and international markets and reducing the incentive for dishonest fishing operators to continue their IUU activities.”

Inspections a Major Part of PSMA

ADF STAFF

Under the Port State Measures Agreement, foreign-flagged fishing vessels might be subject to inspections before they can access ports to offload their catch. Trained inspectors will have to examine vessels and their records to ensure compliance with regulations and laws.

According to the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, vessels seeking port entry will have to provide 23 pieces of information, including vessel name, flag state, owner, certificate of registry, fishing and transshipment authorizations, total catch onboard, and the total catch to be offloaded.

After inspections, inspectors will fill out a 42-point form. Among the things that they must do are:

Verify that onboard vessel identification documentation and ownership information are true, complete and correct.

Verify that the vessel’s flag and markings match the documentation.

Verify that fishing and fishing-related authorizations are true, complete and correct.

Review other documentation and records such as logbooks, catch, transshipment and trade documents, crew lists, stowage plans and drawings, and descriptions of fish holds.

Examine fishing gear to verify that its size, attachments, dimensions and configuration conform to regulations.

Determine whether fish was caught according to applicable rules.

Examine the quantity and composition of fish, including by opening packed containers and moving the catch or containers to examine fish holds.

Evaluate whether there is clear evidence that a vessel has engaged in illegal, unreported and unregulated fishing.

Provide the vessel master a copy of the inspection report. The master will sign and can add comments, objections and contact flag state authorities if he has trouble understanding the report.

Arrange for translation of relevant documentation if possible and necessary.

Inspectors must be properly trained to do this work. Training, as set out by the agreement, will address at least 12 areas. They include ethics; health, safety and security; pertinent national and international laws and other regulations; how to collect, evaluate and preserve evidence; how to conduct inspections, write reports and conduct interviews; analyzing vessel documentation; identifying and measuring fish; identifying and measuring vessels and their gear; vessel equipment operations; and post-inspection actions.