Programs to Deradicalize Extremists Are Necessary and Imperfect

The idealized version of deradicalization is that it happens in an instant. A dedicated jihadist sees the light and chooses to walk away. In this version, he becomes horrified by the violence all around him and decides to abandon the cause. Unfortunately, the reality is much more complex.

Just as people join extremist groups for many reasons, they leave for equally complex reasons. Economic incentives, theological persuasion, disillusionment or the death of a charismatic leader all can cause someone to turn his back on terror. And once he chooses to leave, the real work begins.

Although there is no blueprint for deradicalization, governments are examining what has worked historically in order to implement strategies to deal with radicals at home and battle-hardened fighters returning from abroad. North African countries in particular are grappling with the phenomenon of “radical returnees,” young people who left to fight in Iraq and Syria and return, in many cases, to continue extremism at home. In Tunisia alone, an estimated 1,500 to 3,000 people have left the country to join ISIS. Most will return home at some point.

A starting point for understanding deradicalization is realizing that it doesn’t necessarily mean that a total transformation occurs. Dr. Omar Ashour, an Egyptian-born expert in deradicalization who teaches at the University of Exeter in the United Kingdom, said the core element of deradicalization is that someone renounces violence as a means to accomplish his goals.

“It’s a transition from armed to unarmed activism,” he told ADF. “It means that using violence as a tool for social and political change is a foregone behavior. They shun it, and also they take the extra step of delegitimizing it.”

This does not mean the reformed radical completely changes his worldview. “It’s not a change towards moderation or accepting everybody into the fold,” Ashour said.

Some scholars draw a sharp distinction between the deradicalized individual who renounces hard-line beliefs and accepts democratic, pluralistic values and the merely “disengaged” individual who leaves a terror group and forswears violence.

Rashad Ali, a fellow at the Institute for Strategic Dialogue who works to reform radicalized youth in the United Kingdom, said it is dangerous to stop the process at disengagement. A program has to address the ideology as well. Otherwise, he said, “you’re just containing it and incubating it. You need to have some level of engagement, even if it’s minimal, on understanding the issues that drove them, the issues that pulled them [to extremism].”

SCOPE OF THE PROGRAMS

There are three general types of deradicalization programs, according to Ashour’s research:

Comprehensive programs are the total package. They include changing the ideology of individual extremists, changing their behavior, and dismantling the structure of a terror group. These are the most difficult and costly, but they have the highest long-term success rate.

Substantive programs work with individuals to change their ideology and behavior while not necessarily working with the group as a whole. This can sap the momentum and energy of a group, but it does not get to the root of the problem.

Pragmatic programs do not seek to change the ideology of an extremist but work to change only behavior. This involves pushing the extremist to make a calculated choice to improve his life by abandoning radical behavior to receive certain benefits.

Strategies

In an ideal world, all deradicalization programs would be comprehensive. In reality, a pragmatic approach often is the only available option. Below are some strategies that have worked in various parts of the world. Experts say it is important to use as many strategies as possible because each one confronts the deradicalized person with a barrier to returning to old ways.

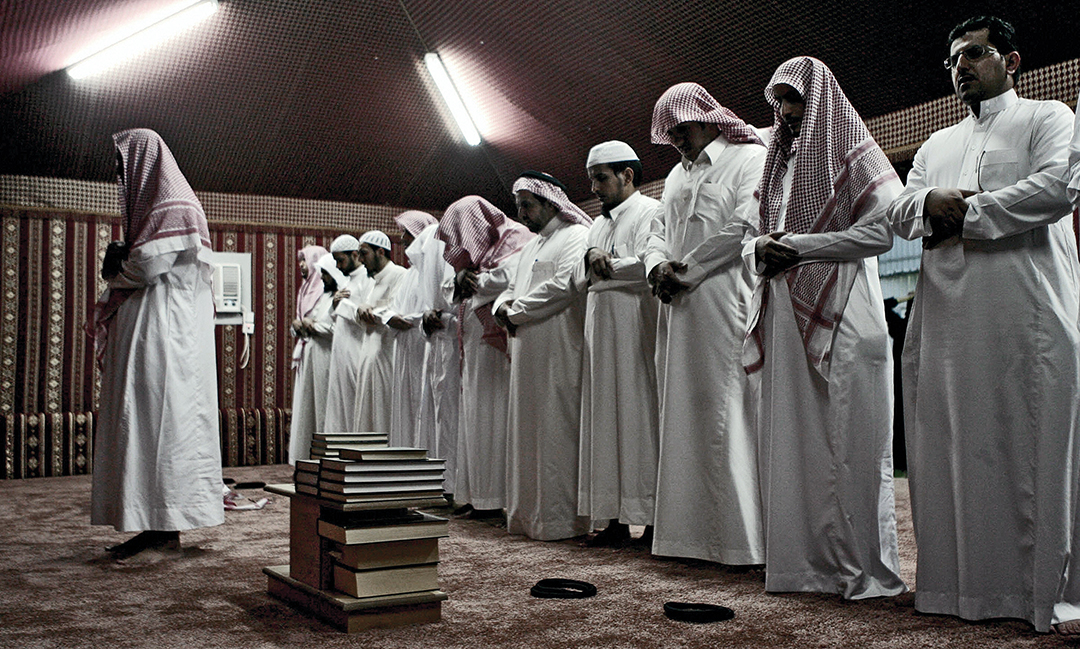

Theological intervention: Radicals often are indoctrinated with religious views that are simply not correct. In fact, many young people recruited into extremist groups have had little or no exposure to religion before joining. This makes them vulnerable to accepting warped teachings.

Deradicalization programs rely on moderate Islamic scholars and imams to sit face to face with these young people and explain that what they have been taught is false. This typically occurs in prison. Ali said theological intervention is effective when it shows a radicalized person that what he is espousing actually violates Islamic tradition. For instance, he said, an extremist book known as the Management of Savagery, which espouses the need to massacre unbelievers — including fellow Muslims — is used by ISIS to justify killings, and is easily refutable by an Islamic scholar.

“You show them that they’re not following the transmitted religious teachings that they claim to be,” Ali told ADF. “That’s our process of engagement. It’s kind of Socratic, questioning, demonstrating, dismantling the falsehood as opposed to trying to persuade them to think something else. When they go through that process, they eventually come to a decision that either the whole thing falls apart, or they’ve had enough of it or they need to move away.”

Some governments, including Saudi Arabia, which purports to have a 90 percent or higher success rate, have institutionalized theological interventions. In 2013, the Saudi government opened a lavish 76,000-square-meter facility that hosts suspected extremists from 41 countries. The rehabilitation program is comprehensive and includes psychological treatment, religious instruction, and help with social reintegration and family reconciliation. This method may be effective, but it is also costly and can be challenging for governments with limited means and a large pool of extremists.

To maximize their impact, other governments are taking a macro approach. Countries are closing down radical mosques and playing a more active role in training moderate imams. For example, in early 2015 Morocco opened a $20 million center to train religious scholars and imams from around the world.

Some have also sought to amplify positive voices and crack down on those who preach hate. After two terror attacks in 2015, Tunisia shut down 80 radical mosques. To delegitimize violence, several countries have sponsored efforts to televise pronouncements by clerics stating that violent acts are against the teachings of Islam.

Idayat Hassan, director for the Centre for Democracy and Development in Nigeria, pointed out that among the first people attacked by Boko Haram in northern Nigeria were clerics and others who disputed the group’s theological teachings. An effective role of a government program could be to help spread the message of those who expose the falsehoods in radical theology.

“There are lots of clerics that have preached against these sects, but who knows about it? There are cassettes, there is video, there are books all over Nigeria actually disputing most of the teachings of this sect [Boko Haram],” she said. “How to scale it up is the challenge.”

Psychological intervention: Although religious war is the prism through which extremists channel their rage, religion does not define it. Syrian journalist Hassan Hassan, who interviewed numerous members of ISIS, said he found that there were six reasons people became radicalized, and only two had anything to do with religion. The most common reasons people join fall into two general categories: First, they want to feel significant, and, second, they want to follow a leader with a clear ideology and who offers them a sense of purpose.

Conversely, a common reason that radicals choose

to leave a terror group is disillusionment, according to

Dr. John Horgan, who has interviewed more than 150 former terrorists. This feeling stems from a disparity between the imagined life of a jihadist and the brutal, depraved life found inside a terror group.

“Some of the former terrorists I’ve interviewed told me they were deeply disillusioned with their groups long before they took steps to leave,” Horgan wrote. “Their reluctance to walk away was, in large part, because they saw no way out. In many countries, de-radicalization is a true second chance at life — the only real alternative to a lifetime in prison or a life on the run.”

This generally means that those who leave or are captured are primed to put their previous life behind them. Psychological counseling can help this process. This one-on-one therapy includes examining the motivations that led to violence, exploring empathy for victims and teaching the person new ways to channel a desire to effect change in the world.

Inducements: Deradicalization programs cannot appeal only to a person’s philosophical and religious beliefs. They also must appeal to cool calculation and self-interest. A wide variety of inducements or incentive programs have proven to be effective at getting radicals to abandon violence. These include offers of amnesty, prisoner release, payments, family protection and job assistance.

Although some may find it distasteful to reward people for violent behavior, experts say it is vitally important. “I don’t know of any successful [deradicalization] case that omitted inducements,” Ashour said. “All the successful cases from Indonesia to Morocco employed inducements. It ranged from better prison conditions at a minimum all the way to a power-sharing formula at the maximum.” Ashour added that inducements are best used selectively and as part of a comprehensive deradicalization package.

One inducement that is often overlooked, but is highly effective, is protection for families. In Algeria in the early 2000s, some members stayed inside extremist groups out of fear that their cohorts would take vengeance on their families if they left. Similarly, Boko Haram has blackmailed young people into joining the group by threatening family members. If governments can offer protection or relocation services to families of defectors, those defectors are less likely to return to the group or “reradicalize.”

Leadership: When the power structure of an extremist group is dismantled and charismatic leaders are co-opted or removed from the battlefield, it becomes far easier to deradicalize foot soldiers. This has been proven time and again. In 1997 in Algeria, Army Gen. Isma’il Lamari risked his life and his professional credibility when he traveled to the mountain stronghold of the Islamic Salvation Army (AIS) to hold direct peace negotiations with its leader. The gambit worked, and he was able to get AIS leadership to renounce violence, which proved to be the first step in getting the entire organization to lay down arms. In the 1990s in Egypt, the imprisoned leaders of two groups, al-Gama’a al-Islamiyya and Egyptian Islamic Jihad, underwent theological interventions with respected scholars and imams, and they decided to renounce violence. This message was relayed to fighters across the country who followed suit.

In each case, the lesson is that leadership matters in deradicalization, and persuading leaders to lay down arms is a game-changer. A study by the Rand Corp. of 268 terrorist groups that were active between 1968 and 2006 found that only 7 percent of them were ever defeated militarily. A much higher number, 43 percent, chose to lay down arms and pursue their causes through the political system or through direct negotiations with the government.

“You deal with the commanders, the selected few, and the commanders themselves sell the idea to the mid ranks and the grass roots,” Ashour said. “If they are charismatic enough and the grass roots believe in them enough, it usually becomes quite successful.”