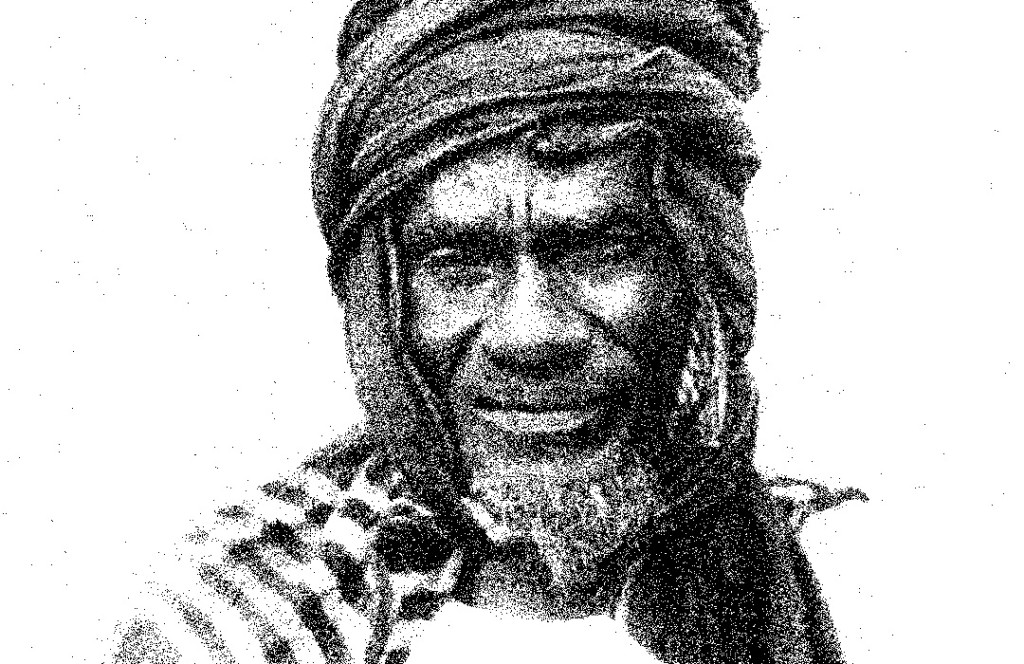

Samori Touré was a great warrior, a natural leader and an empire builder. But he is perhaps best remembered, and honored, for his role in his later years — defiant to the end to his would-be conquerors. Almost 60 years after his death, his grandson was equally defiant.

Touré was born in about 1830 in what is now Guinea. Like his father, he became a merchant. That ended when he was 20 and his mother was kidnapped in a slave raid. The young but already-skilled merchant-negotiator bargained with her captor, offering to serve in his army in exchange for his mother’s release. The offer was accepted, and Touré’s life was forever changed, as he proved to have extraordinary military and leadership skills. After a time, King Sori Birami relieved him from further service and released his mother.

Touré was keenly aware that his people, the Malinke, lacked discipline and leadership. There was no single chief with the authority to take charge. He declared himself independent of King Birami and began building an army of his own. His Soldiers were well-disciplined, and he began expanding his territory, using his considerable negotiating skills — along with threats of war.

He established a new empire called Mandinka, declaring himself its king and commander in chief. He won the nickname “Napoleon of the Sudan” from his opponents as he established his capital in what is now The Gambia and continued to expand his empire. If it still existed today, it would include parts of Guinea, Liberia, Mali and Sierra Leone.

After the partitioning of Africa in 1884, European powers began colonizing West Africa. They had no tolerance for strong rulers such as Touré and did not recognize his authority. When he refused to submit, they began military action.

Touré’s estimated 35,000 skilled warriors, armed with modern European weapons, initially stopped French invaders. France responded with more forces, which included Senegalese fighters. After more battles, Touré signed treaties with the French in 1889.

Within two years, the French had broken the treaties and were sowing rebellion within Touré’s territory. He took up arms again and signed a treaty with the British, obtaining additional modern weapons in the process. As the French continued to advance into his territory, he moved his entire empire east, conquering large parts of what is now Côte d’Ivoire. He established his new capital there.

On May 1, 1898, French forces invaded a town just north of the new capital. Touré positioned his fighters in the Liberian forests to stop the French troops. It became a war of attrition, with Touré’s troops starving and deserting. The French captured Touré and exiled him to Gabon, where he died of pneumonia two years later, on June 2, 1900.

In 1959, Charles de Gaulle became president of France and proposed the creation of the French Community, similar to the British Commonwealth. In exchange for accepting the new authority, the French territories would receive financial aid. All the territories but one voted to accept the new arrangement. The lone exception was Guinea — led by Touré’s grandson, Sekou Touré.