A Booming West African Economy Faces Seaborne Threats

The Gulf of Guinea finds itself at a critical moment in its history. The promise of economic growth and the danger of maritime crime are pushing the region in opposite directions. And like a ship beset by a storm, only the hands of skilled sailors can help the region navigate the rough waters.

First, the good news: West Africa’s economies are booming, and the Gulf is an important part of that growth. It’s a major route for shipping oil all over the world. Container shipping traffic is up. The Gulf’s mild, predictable climate is ideal for commerce, fishing and docking. It offers a relatively short shipping lane between Africa and South America. And one of the Gulf countries, Nigeria, has the largest economy on the continent.

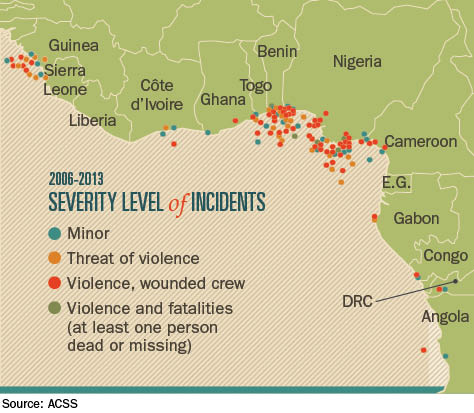

But there is trouble as well. The Gulf has the dubious distinction of having more reported pirate attacks than any other region in the world, eclipsing the attacks by Somali pirates in the Gulf of Aden. According to various estimates, piracy in the Gulf costs the region between $565 million and $2 billion each year.

The reported attacks may be only the tip of the iceberg. The International Maritime Bureau and Oceans Beyond Piracy say that about two-thirds of pirate attacks off the coast of West Africa go unreported. Kidnappings and paid ransoms are sometimes kept secret as well. Overall, OBP estimates that governments and the shipping industry are spending as much as $983 million to combat maritime piracy in the region each year.

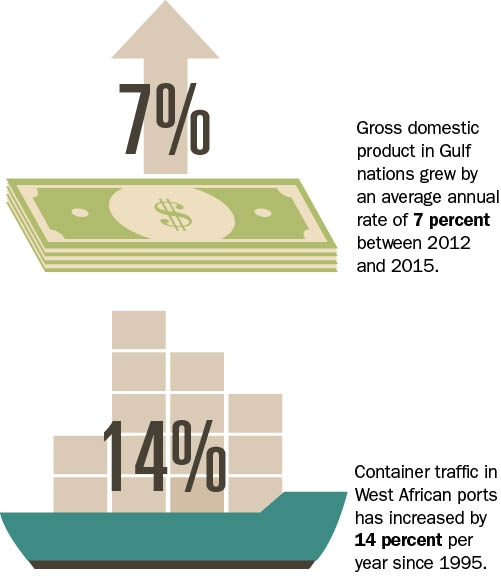

PORT TRAFFIC

African economies are growing, and the Gulf of Guinea is positioned to be the continent’s entry point. Gross domestic product in Gulf nations grew by an average annual rate of 7 percent between 2012 and 2015. Business at ports is booming at an even higher rate. Container traffic in West African ports has increased by 14 percent per year since 1995. That is the largest growth of any region in Sub-Saharan Africa, according to a paper published by the Africa Center for Strategic Studies.

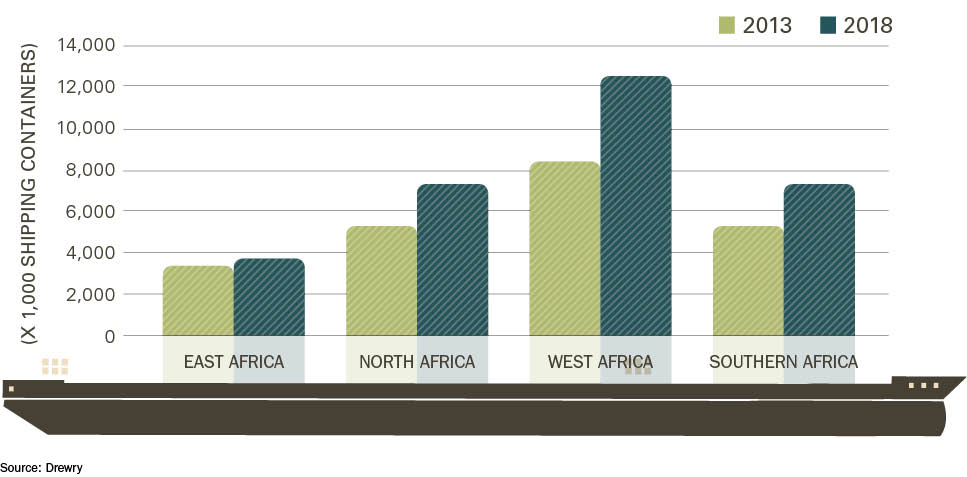

Maritime commerce promises to keep expanding in coming years. The French shipping giant Bolloré is enlarging its terminal in Lomé, Togo, and the Ghanaian port of Tema is beginning a $1.5 billion expansion. Both projects are expected to be complete by 2017. Other expansions are planned in Côte d’Ivoire, Republic of the Congo, Nigeria and Senegal. By 2020, a total of nine planned projects will give West African ports the ability to handle about 11.5 million additional shipping containers, the Drewry Shipping Consultants reported.

VOLUME PROJECTIONS 2013 – 2018

OIL

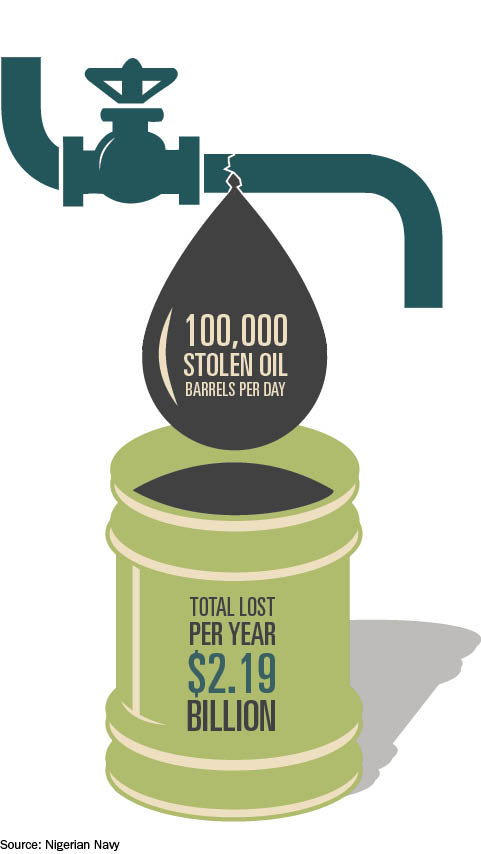

West Africa is the in midst of an oil boom. The region accounts for about one-third of the new oil discoveries worldwide, with the latest oil field discoveries off the coast of Ghana, Liberia and Sierra Leone. In all, the West African coast boasts an estimated 3.2 billion barrels of oil, according to the U.S. Geological Survey. But there is trouble in these waters. Illegal oil bunkering has reached epidemic proportions in Nigeria and elsewhere. The dangerous practice, which often involves criminals puncturing a pipeline and collecting oil in a bucket, causes the loss of about 100,000 barrels of oil per day in Nigeria, a cost of nearly $6 million, according to the Nigerian Navy. Some estimates place the total much higher. Bunkering also causes spills that spoil the environment and explosions that can kill large numbers of people.

ILLEGAL FISHING

For every 14 Fish caught 4 are stolen Total Cost of IUU Fishing: $350 million per year

Fishing is vital to the economies of many West African nations. In Senegal, 25 percent to 30 percent of the nation’s exports come from fisheries. In Ghana, about 7 percent of the working population is employed directly by the fishing sector, according to a European Union (EU) report. For many, it is a way of life that has gone virtually unchanged for centuries. Dugout canoes, hand-sewn nets and sails are still widely in use. But this way of life is under attack. Large foreign trawlers without proper permitting are scooping up vast amounts of fish from West African waters. According to the EU, illegal, unreported and unregulated fishing in the Gulf of Guinea costs coastal states $350 million per year. The total number of catches in this region is believed to be 40 percent higher than what is legally reported. The practice not only decimates a precious natural resource, it also costs jobs and fosters resentment among fishermen in coastal communities. In other parts of the world, unemployed fishermen have turned to piracy as a way to make ends meet.

NAVY/COAST GUARD FLEETS

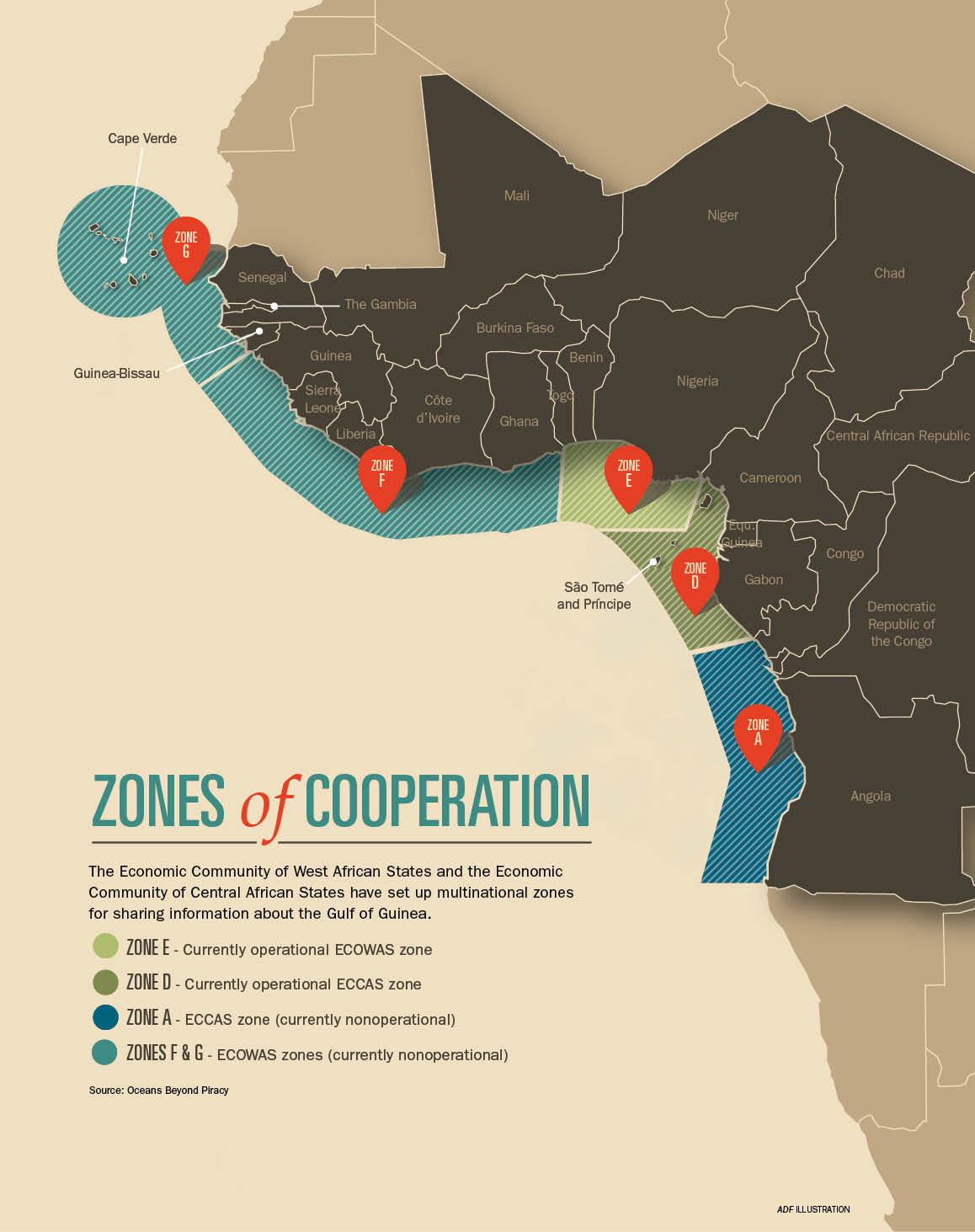

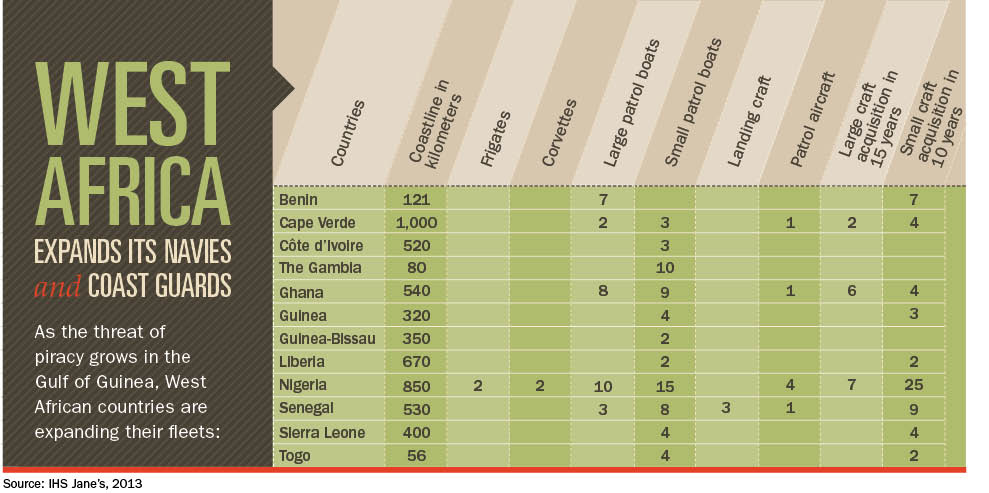

In response to emerging threats and recognizing the importance of commerce in the Gulf, many coastal countries are beefing up their navies and coast guards. Historically, maritime security has been secondary in funding and perceived importance to other security needs in Africa. That is no longer the case. The newfound status was on display in February 2015 when the Nigerian Navy put four new warships into service, the most ever commissioned at one time. Angola is undergoing a rapid expansion of its navy to protect its offshore oil wealth.

Still, many Gulf navies and coast guards are underequipped for extensive patrolling and pursuits, leaving their ports vulnerable. Although nine Gulf nations plan to acquire additional large patrol ships, those plans are often years in the future.

KIDNAPPING/HIJACKING

In 2012, the Gulf of Guinea surpassed the coast of Somalia to become the region of the world with the greatest number of pirate attacks. In 2014, 1,035 seafarers were subject to attacks, and 170 were detained or held hostage. Most pirate attacks in 2014 were farther offshore in international waters, indicating the work of more sophisticated pirate networks. More than half of the attacks involved weapons. Among those believed to be involved in piracy are Nigerian gangs, “insiders” in the oil industry, crooked security workers, and organized criminal networks from Eastern Europe and Asia. Piracy attacks in the Gulf now make up

19 percent of all recorded maritime crimes worldwide.

The world’s commercial shipping companies are taking notice. Insurance underwriters have designated the waters off Benin, Nigeria and Togo as a “war risk area,” which drives up insurance costs.