Militaries Mobilize Against a New Enemy

Soldiers, police and civilians join forces to halt the spread of one of earth’s deadliest diseases.

Two-year-old Emile Ouamouno lived in a home like many others in his native Guinea. His small, rain forest village of Meliandou was close to the borders with Liberia and Sierra Leone. Like most in the region, his family gathered its food from the plants and animals found in the area.

Wild fruit bats are among the plentiful and popular food sources. Several varieties are indigenous. The boy’s family had hunted two types — the hammer-headed bat and Franquet’s epauletted fruit bat — in late November or early December 2013. His mother might have grilled the flying mammals or cooked them in a soup. Emile might have played at her feet as she prepared a meal.

Maybe, in childlike curiosity, he touched one of the bats, running his chubby little finger across its furry back or leathery wings. Then perhaps he touched his mouth, as children do. Maybe that is all it took.

On December 2, 2013, Emile became ill with fever, black stools and vomiting. Four days later he was dead.

The boy’s mother died December 13, 2013. His 4-year-old sister, Philomène, became sick on December 25, 2013. She, too, died after four days. The children’s grandmother died January 1, 2014, and a nurse and a village midwife died on February 2, 2014, after being ill only a few days.

The grandmother’s sister and another person from Dawa village attended the grandmother’s funeral. Both died. A relative of the midwife, who cared for her kin, died in Dandou Pombo village. In the four months after Emile died, 14 Meliandou residents died, according to CNN.

What likely started with a small fruit bat and a young boy was on its way to becoming a ferocious cross-border killer as it marched into nearby Liberia and Sierra Leone. The virus, which resembles a twisted bootlace when viewed with a high-powered microscope, was tightening its grip on an unsuspecting region. Ebola had been unleashed.

WHAT IS EBOLA?

Ebola virus disease, also known as Ebola hemorrhagic fever, is a highly lethal viral infection that stems from four viral strains known to cause harm in people. As a threat to humans, it appears to be relatively new. The first known case was in the former Zaire, now the Democratic Republic of the Congo, in 1976. The disease was named for its proximity to the Ebola River.

Since then, Ebola has emerged in several African countries through the years, never killing more than 280 people in a single outbreak. Until now.

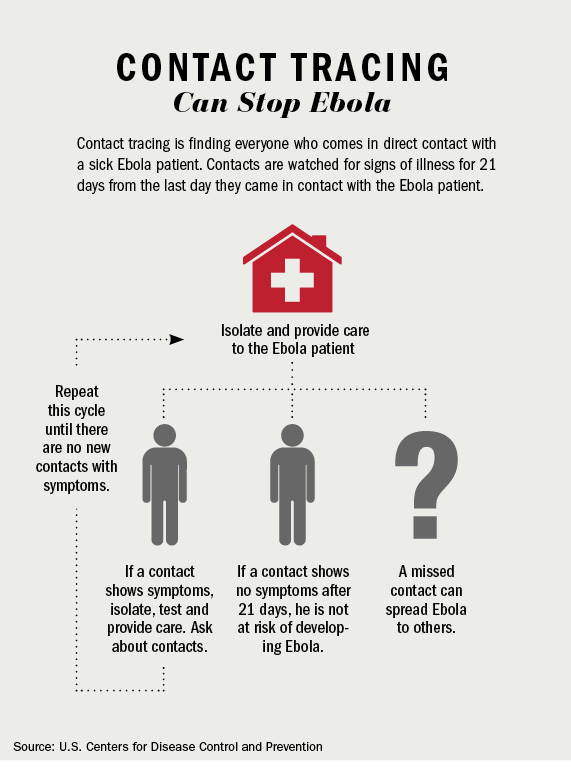

The disease can take up to 21 days to manifest itself in a person after exposure. Symptoms usually include fever, vomiting, diarrhea, severe headaches, muscle and abdominal pains, and hemorrhaging. Some people eventually recover, but Ebola at its most lethal has killed nearly nine of every 10 people it infects.

It is spread via close contact that involves bodily fluids. Burial customs, in which mourners clean and touch bodies, are believed to have contributed to the spread of Ebola in West Africa.

The outbreak that started in Guinea and crossed into Liberia and Sierra Leone is the biggest in known history. Although it’s possible that Ebola killed people before 1976, there is no record of earlier outbreaks.

The virus is known to exist in a variety of animals, including apes, monkeys and antelope, but its natural host is probably the fruit bat. Five types of fruit bats are common to West Africa. Often people eat the bats and other infected animals. The practice has been cited multiple times as the likely cause of human illness.

RESPONDING TO A PANDEMIC KILLER

Disease is no stranger to Africa. The continent is home to the “meningitis belt,” which stretches from Eritrea west to Senegal. Malaria is a problem across much of the continent, and cholera outbreaks are common, particularly during rainy seasons. Pandemic flu outbreaks are perennial threats in Africa and beyond. But Ebola is different. Outbreaks are not particularly common. The disease lives in the shadows of dense jungles and remote villages. If a man in an isolated village handles or eats a dead chimpanzee, for example, he may contract the disease and even spread it to friends and family members. But the high mortality rate sometimes causes Ebola to burn out before it becomes widespread.

In the West African outbreak, proximity to dense population centers such as Monrovia, Liberia, allowed the disease to spread faster than medical personnel were able to react. Hospitals and medical facilities became overwhelmed quickly.

Fear associated with the disease also has had a deadly cascading effect. People with treatable maladies such as pneumonia, diarrhea and malaria have avoided hospitals for fear of contracting Ebola. Sometimes, nervous health workers turn away the sick out of fear of the disease. Both can increase the spread of Ebola and lead to preventable deaths.

“If you stub your toe now in Monrovia, you’ll have a hard time getting care, let alone having a heart attack or malaria,” Sheldon Yett, Liberia’s representative for the United Nations Children’s Fund, told The Washington Post in September 2014. “It’s a tremendous threat to children and a tremendous threat to families.”

The Ebola crisis also has taken the focus off curable diseases, such as polio. Guinea, Liberia and Sierra Leone sat out a recent 18-nation polio immunization campaign, according to U.S.-based NPR. Other childhood vaccinations, such as measles, also are falling by the wayside.

Liberian President Ellen Johnson Sirleaf told The Associated Press in August 2014 that the outbreak had to be met with “extraordinary measures for the very survival of our state and for the protection of the lives of our people.”

“Ignorance, poverty, as well as entrenched religious and cultural practices continue to exacerbate the spread of the disease, especially in the counties,” Sirleaf said.

EFFECTIVE COMMUNICATION IS KEY

Among the early ways Ebola spread in West Africa was through funeral and burial customs in which mourners touched and sometimes washed bodies of those who had succumbed to the disease. This close physical contact with infected bodies was a prime mode of transmission.

Recalcitrance in some communities to relinquish bodies to health authorities led to clashes and distrust in a crucial stage of the outbreak, when control of the spread was essential. Furthermore, some of these same groups may well have been exposing themselves to the virus through the consumption of wild forest animals, known as bush meat.

Dr. Mark J. Walters, a veterinarian and journalism professor at the University of South Florida-St. Petersburg in the United States, said it can be difficult for Soldiers and public health officials to communicate important medical information to civilian populations that adhere to age-old traditions. And yet, this communication is crucial.

“I think one universal way that works is the notion of embedding scientific information in story or parable,” Walters said. “It’s really about stories. It’s not about information per se. We, I think, as humans are hard-wired for stories. That’s what we understand, that’s what we tell each other, and this whole idea of scientific communication is really rather new, and it’s an acquired thing — it’s not built into the way we think.”

He said booklets containing simple “picture stories” could be effective in illustrating symptoms and precautions for civilians.

An artist in Monrovia, Liberia, painted wall murals with vivid images of people and faces that illustrated all the symptoms of Ebola. Thousands of people walked and drove by the mural each day. “That artist has got exactly the right idea,” Walters said.

WEST AFRICAN MILITARIES RESPOND

Ebola is a frightening disease. Its lethality and the ignorance about it among many civilian populations can quickly spawn unrest and civil disorder. This happened during the West African outbreak. Some people believed government officials fabricated the outbreak as a ruse to get millions of dollars in Western aid money. Others became convinced that if they went to Ebola treatment facilities, they would become sick and even die. Some people, infected with Ebola, left hospitals and tried to return to their homes, taking the highly infectious disease back into population centers.

It quickly became clear that military involvement was essential. “What is critical in order to make this care successful is to have a strict monitoring, a strict supervision, a good chain of command,” Sophie Delaunay, executive director of Doctors Without Borders, told NPR in mid-September 2014. “This is key. And this is why we do value the role of the military in this intervention, and we would actually wish that there would be much greater mobilization of military assets and personnel, because they are much better equipped than any nongovernmental organizations to put in place those kind of very strict and solid supervision from A to Z.”

By that time, West African militaries already were mobilizing efforts to combat and contain Ebola’s spread. Liberian Soldiers were called upon to keep people from traveling to Monrovia from outlying areas in August 2014. The nation emerged as the epicenter of the outbreak with the most cases. With hospitals and medical personnel at a premium, Ebola patients sometimes died in the streets or lay slumped at the gates of treatment hospitals because no beds were available. In the capital, taxis emerged as a prime mode of disease transmission because infected patients used them to get to care centers.

A simple lack of medical resources also conspired with other factors to sustain Ebola’s spread.

“As soon as a new Ebola treatment facility is opened, it immediately fills to overflowing with patients, pointing to a large but previously invisible caseload,” the World Health Organization told the BBC in September 2014. “When patients are turned away … they have no choice but to return to their communities and homes, where they inevitably infect others.”

In Sierra Leone, one of three West African nations battling the disease, the Republic of Sierra Leone Armed Forces (RSLAF) organized Operation Octopus. In early August 2014, 54 RSLAF medical workers were among 750 military personnel deployed to Kailahun and Kenema districts in support of the Ministry of Health and Sanitation and the Sierra Leone Police in the fight against Ebola, according to RSLAF Capt. Yayah Sidi Brima.

Brima reported that RSLAF Brig. Gen. Brima Sesay said the unarmed military operation would include securing disease epicenters, quarantine areas and government hospitals, and establish checkpoints and mobile patrols.

In October 2014, 65 RSLAF personnel in the Sierra Leonean cities of Freetown, Makeni and Bo were trained by Ireland-based nongovernmental organization GOAL so that they could train an additional 1,630 RSLAF Soldiers deployed nationwide to help the Ministry of Health and Sanitation fight Ebola.

In October 2014, 65 RSLAF personnel in the Sierra Leonean cities of Freetown, Makeni and Bo were trained by Ireland-based nongovernmental organization GOAL so that they could train an additional 1,630 RSLAF Soldiers deployed nationwide to help the Ministry of Health and Sanitation fight Ebola.

Brima reported that the training would teach RSLAF personnel how to protect themselves and their communities from Ebola.

Sierra Leone also imposed a three-day lockdown September 19-21, 2014, in hopes of halting the spread of the disease. The lockdown was met with skepticism by medical professionals, who claim such tactics “end up driving people underground and jeopardizing the trust between people and health providers,” Doctors Without Borders told The Washington Post. “This leads to the concealment of potential cases and ends up spreading the disease further.”

The United States deployed more than 3,000 military personnel to Monrovia to construct Ebola treatment units, known as ETUs. Each ETU will provide 50 to 100 beds throughout the city and to the north and south. Officials expected the ETUs to be complete by the end of December 2014.

THE AFRICAN UNION RESPONDS

The African Union’s Peace and Security Council in August 2014 authorized deployment of a joint military and civilian humanitarian mission in response to the Ebola outbreak.

The African Union Support to Ebola Outbreak in West Africa (ASEOWA) deployed civilian and military volunteers from across the continent. Mission personnel include doctors, nurses, and other medical and paramedical workers. The $25 million operation was expected to run for six months with a monthly volunteer rotation. The effort was meant to complement the work of the World Health Organization (WHO), the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and other agencies.

The mission was the first of its kind by the AU. Initially, 30 volunteers joined Ugandan Maj. Gen. Julius Oketta, head of mission for ASEOWA, in Liberia. (See interview with Maj. Gen. Oketta on page 30). Oketta has extensive experience in emergency management in his home country, where he is director of the country’s National Emergency Coordination and Operations Centre.

The first 30 volunteers underwent predeployment briefings at the AU headquarters in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, before their September 2014 departure for West Africa. Their ranks included epidemiologists, clinicians, public health specialists and communications workers from the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Ethiopia, Nigeria, Rwanda and Uganda.

According to the AU, ASEOWA offers “technical expertise, resources, political and financial support” to humanitarian assistance, and is able to coordinate support and “support public awareness and preventive measures across Africa and specifically in the affected region.”

A second batch of volunteers was scheduled to follow in Sierra Leone as the operation expands.

“You are unique in that you will be carrying the African banner in your mission,” Dr. Mustapha Sidiki Kaloko, AU commissioner for social affairs, told volunteers before they left for Liberia. “This is the time for Africa to show solidarity with the affected countries.”

Ebola Timeline

no. sick/died

- 1976: Sudan 284/151, Zaire 318/280

- 1977: Zaire 1/1

- 1979: Sudan 34/22

- 1994: Gabon 52/31, Côte d’Ivoire 1/0

- 1995: DRC 315/250

- 1996: South Africa 2/1, Gabon 37/21

- 1996-97: Gabon 60/45

- 2000-01: Uganda 425/224

- 2001: Congo 57/53, Gabon 65/53

- 2002-03: Congo 143/128

- 2004: Sudan 17/7

- 2007-08: DRC 264/187, Uganda 149/37

- 2008-09: DRC 32/15

- 2011: Uganda 1/1

- 2012-13: DRC 36/13, Uganda 11/4, Uganda 6/3

- 2013: Congo 35/29

- 2014: DRC 66/49

- 2013-14: West Africa* 17,942/6,388

*Countries affected in descending order of cases as of December 11, 2014: Sierra Leone, Liberia, Guinea, Nigeria, Mali, the United States, Senegal and Spain.

How to Prevent Contraction, Spread of Ebola

Ebola is a deadly viral hemorrhagic fever, part of a group of viruses that attack several organ systems in the human body and often cause bleeding. There are five strains of the virus, and four of them are known to infect people. The West Africa outbreak is from the Ebola Zaire strain, the most common and deadliest to date.

How Ebola spreads

The virus spreads through contact with bodily fluids of an infected person. Transmission is not thought to be possible until an infected person is symptomatic. But once that occurs, the blood, sweat, saliva, stool, vomit, urine, breast milk and semen of an infected person can spread the disease if the fluid enters an open wound or a part of the body covered by a mucus membrane, such as the eyes, nose and mouth.

According to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, other methods of transmission include objects such as needles and syringes contaminated by the virus, and infected animals. The handling and ingestion of wild animals hunted for food, commonly called bush meat, can spread the disease if the animal is infected. Bats, monkeys, chimpanzees and pigs have been known to carry Ebola.

Mosquitoes and other insects do not transmit Ebola, and there is no evidence the disease is spread by air.

A person who recovers from Ebola may still be contagious through semen for up to three months. For that reason, people who recover from Ebola are advised to abstain from sex for three months or use condoms during that period.

How to prevent Ebola

The World Health Organization recommends these steps to avoid contracting Ebola:

- Do not touch sick people who exhibit Ebola symptoms such as fever, diarrhea, vomiting, headaches and sometimes heavy bleeding.

- Do not touch the dead bodies of suspected or confirmed Ebola patients.

- Wash your hands with soap and water regularly.

Experts also say that people should avoid contact with bats and nonhuman primates or the blood, fluids and raw meat prepared from these animals.

If you go to an area where Ebola is prevalent, monitor your health for 21 days and seek medical care immediately if you develop Ebola symptoms.

Ugandan Lab

a Valuable Tool in the Fight Against Deadly Diseases

Ebola is no stranger to Uganda. Since 2000, two strains of the deadly disease — Sudan virus and Bundibugyo virus — have struck the country a total of five times, killing 269 people in all, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

Other diseases also frequently infect Ugandans. They include yellow fever, HIV/AIDS, Rift Valley fever and Marburg, a viral hemorrhagic fever similar to Ebola. For years, Uganda has had an essential tool in studying and responding to such illnesses: the Uganda Virus Research Institute (UVRI) in Entebbe.

The Rockefeller Foundation established the UVRI in 1936 as the Yellow Fever Research Institute. In 1950, it became the East African Virus Research Institute. It was renamed the UVRI 27 years later. Among its many milestones since inception are:

- Isolation of chikungunya and West Nile viruses at the institute in 1937. Chikungunya causes fever, joint pain, and sometimes headache, muscle pain, joint swelling and a rash. West Nile, also spread by mosquitoes, sometimes causes fever and other symptoms.

- Discovery of Bwamba fever, transmitted to humans by mosquitoes, in the 1940s. This illness, often mistaken for malaria, causes fever, headache, backache and other symptoms.

- Isolation in 1942 of Semliki Forest virus, another mosquito-borne disease. Semliki Forest virus causes mild symptoms, including headache, fever, and muscle and joint pain.

- Isolation of O’nyong’nyong virus in 1959. The name means “weakening of the joints” and is similar to chikungunya.

- In 1997, the CDC set up a center at the UVRI.

- In 1999, the UVRI collaborated on the first HIV vaccine trial in Africa.

- The International AIDS Vaccine Initiative started collaborating with UVRI on HIV/AIDS vaccine research in 2000.

The UVRI also gives Uganda some distinct advantages when an Ebola outbreak occurs.

“Uganda has historically handled these cases very well,” Trevor Shoemaker, an epidemiologist at CDC’s Viral Special Pathogens Branch in Uganda, told IRIN. “If there is a suspected case of Ebola, local health officials follow a process for investigating and reporting a suspect sample through DHIS 2 [the District Health Information System].”

In Uganda, a Village Health Team member or district health worker notifies district officials of suspected Ebola cases. If the patient is found to meet the criteria of such a case, he is taken to a medical facility, blood is drawn and he is isolated until lab tests are complete.

The sample is registered and sent to the UVRI and CDC for testing. The time needed to take a sample, test it and report the results is 24 to 48 hours. In the past, and in other places without such facilities, such tasks could take weeks.

“With CDC’s support, Uganda now has the ability to test samples within 24-48 hours of receiving them and this allows a response team to be deployed to the [affected] district to begin a rapid response quickly,” Shoemaker said. “This time factor alone can greatly reduce the total number of cases because you can rapidly identify new cases and monitor contacts.”

Asuman Lukwago, permanent secretary at Uganda’s Ministry of Health, told IRIN the capacity brings peace of mind and saves lives. “Previously, we could take those specimens to Atlanta [in the United States] and this could take us about two to three weeks when we are fidgeting, and this could allow time for transmission of epidemic to take place. But now, we can quickly confirm and therefore alarm the public and everybody becomes cautious.”

If Ebola strikes, Ugandan officials work with the World Health Organization, the CDC, Doctors Without Borders, the Uganda Red Cross and other nongovernmental organizations to provide lab support and a communications campaign, said Issa Makumbi of the Ministry of Health. A national task force coordinates health teams from the national to the village level, and politicians work to inform the public.

CDC’s lab in Entebbe has helped Uganda identify eight hemorrhagic fever outbreaks in the past four years. Uganda is able to do the same types of diagnostic work being done in West Africa faster and at a much earlier stage. Also, because Ebola and similar diseases are not new to Uganda, civilians are more likely to seek medical care, allowing for quicker overall response, Shoemaker said.

“We, too, panicked during the first outbreak in 2000, which killed one of our doctors,” Lukwago told IRIN. “Everybody looked at Ebola as a mysterious disease. But from then, we noted that we are always prone to getting Ebola. So every time we have a suspected case, we are well ready to handle the worst scenario. So it has become less of a crisis.”

The DHIS 2 reports suspected cases, sends emails and SMS alerts, and uses radio and TV to get the word out about outbreaks.

“If we got an outbreak of Ebola in any part of Uganda, a majority of people who have telephones will be able to know in one hour or two hours through SMS alerts,” Lukwago said. “We, too, communicate through radio and television, which [the] majority of people have. By the end of the day, almost every Ugandan is aware of Ebola outbreak.”