SSR Offers Stability for Governments and PROTECTION for Civilians

ADF STAFF Photos by THE ASSOCIATED PRESS

Leaders considering the necessity of security sector reform (SSR) need look no farther than the small West African nation of Guinea-Bissau. Today the country of nearly 1.7 million is known primarily as a “narcostate” for the impunity with which South American drug traffickers push cocaine through the nation on the way to Europe.

Instability has plagued Guinea-Bissau since its independence from Portugal in 1974. No president has finished a full term in office. The European Union began SSR in 2008 but suspended the effort two years later after a coup. From 2009 to 2012 alone, there were six significant political assassinations and three attempted coups, according to the Security Sector Reform Resource Centre.

Four months after President Malam Bacai Sanhá died of natural causes in January 2012, Bissau-Guinean Soldiers arrested the leading presidential candidate and seized government and media operations. A few months later, the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) worked with the transitional government on a plan that included SSR, rekindling the embers of hope that past intransigence would give way to real reform. Understandably, skepticism remains.

Conversely, in Africa’s Great Lakes region, Burundi has achieved some success with its SSR efforts. A 2012 panel on SSR in East Africa found that Burundi’s process was “at a crossroads.” Security forces, once out of balance with regard to ethnicity, region and politics, have improved through integration and demobilization. Burundians serve in the African Union Mission in Somalia and other United Nations peacekeeping missions. But according to a 2012 Human Rights Watch report, work still is needed to prevent human rights violations and to strengthen civilian oversight.

SSR is underway across the continent: Burundi, the Central African Republic, Côte d’Ivoire, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Guinea-Bissau, Guinea (Conakry), Liberia, Libya, Somalia and South Sudan all have SSR efforts representing a range of progress and success. Nations serious about SSR will have to embrace some important principles and commit to a lengthy process requiring patience and discipline.

DEFINING SECURITY SECTOR REFORM

SSR is not easily defined, but is characterized by a series of overriding principles. Agencies and nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) have applied their own interpretations to the term.

The United Nations says SSR is “a process of assessment, review and implementation as well as monitoring and evaluation led by national authorities that has as its goal the enhancement of effective and accountable security for the State and its peoples without discrimination and with full respect for human rights and the rule of law.”

The International Security Sector Advisory Team (ISSAT), a division of the Geneva Centre for the Democratic Control of Armed Forces, outlines one set of core principles.

ISSAT explains that effective SSR has these areas of focus: First, its approach is through local ownership. Its two core objectives are increased effectiveness, balanced with increased accountability. Finally, it has three essential dimensions: political sensitivity, a holistic vision and technical complexity. Here’s a closer look at these areas.

Local ownership: Reform should be “designed, managed and implemented” by those in the nation undertaking SSR, not external actors. This is not synonymous with government ownership. Instead, it should involve people at all levels, especially those outside security and justice sectors. This ensures that SSR responds to local needs and bolsters the legitimacy of those in security and justice. ISSAT stresses this point: “Without local ownership, SSR is likely to fail.”

Increased effectiveness and accountability: Effectiveness simply means improving security to enhance the well-being of the nation and its citizens. This can be accomplished in many ways, such as building skills through training, providing equipment, and improving organization and management. Accountability requires checks and balances to make sure those in the security sector follow laws and avoid abuses. Codes of conduct, parliamentary oversight, judicial review and civilian review can provide formal accountability. Civil society groups, religious groups, the media and NGOs can provide more informal accountability. However, ISSAT says accountability typically receives little attention. This can prevent SSR from functioning as it should and hamper long-term success.

Political sensitivity, holistic vision and technical complexity: SSR efforts are essentially political undertakings. SSR will require “political understanding and sensitivity, analytical, research and negotiation skills, tact and diplomacy,” according to ISSAT. SSR must be inclusive and flexible. Time and patience are essential.

SSR is a holistic enterprise in that it involves multiple participants and stakeholders: defense, police, intelligence agencies, the court system, and public and government oversight, among other things. For example, if SSR tries to change the police force, it must engage the justice and corrections sectors to ensure success.

SSR also is technically complex in that it requires knowledge and experience in multiple areas, including the various arms of the security sector, and budgeting, logistics, training and more. Nations attempting SSR will have to strike a balance between political and technical expertise.

CHARACTERISTICS OF SUCCESSFUL REFORM

Guinea-Bissau has been unsuccessful at SSR because it lacks some basic conditions necessary to flourish, according to Boubacar N’Diaye, chairman of the African Security Sector Network.

“It is a political process, and so I think the basic characteristic of a successful SSR would be the real, genuine existence of political will to carry it out, to carry it through,” said N’Diaye, a native Mauritanian. “And when that obtains, typically, SSR has a good chance of succeeding.” Absent that political will, he said, countries are destined to get stuck in an endless cycle of conflict and instability.

In addition to this national ownership, N’Diaye said nations must have the capability to mobilize their own resources to get the job done. “Unfortunately, many African countries cannot do that, and depend heavily — if not entirely — on foreign aid to be able to carry out SSR,” he said.

Many countries that need SSR the most are coming out of conflict and civil wars. As a result, the demand for national resources — for humanitarian purposes and infrastructure — can be overwhelming, pushing SSR into the background. In some nations, hostilities continue to break out. South Sudan is an example of this. Although the United Nations Mission in the Republic of South Sudan has an SSR component, conditions there are not conducive to promoting it.

Add to these challenges the need for capable expertise on the ground and the support of those in the security forces, N’Diaye said. Successful SSR requires commitment on multiple levels and can take several years to bear fruit and even longer to complete. Africa’s SSR success stories continue to be works in progress, N’Diaye said.

South Africa’s program has achieved some success because the will, and need, to reform was strong as apartheid ended, he said. To an extent, the same is true for Côte d’Ivoire and Sierra Leone. The context is different in that both nations undertook SSR after years of violent conflict. Côte d’Ivoire did so as part of the United Nations Operation in Côte d’Ivoire, and Sierra Leone did so with the help of the United Kingdom. Both have made significant achievements, but much work remains.

“Success, as you know, is quite relative, first, and of course SSR is a long-term process,” N’Diaye said. “And, of course, you can have dramatic reversals and you can have conditions that change to jeopardize even the most promising project.” SSR generally began in the 1990s, so even older programs, such as the one in South Africa, are new enough that “the jury is out,” he said.

THE BENEFITS OF REFORM

When done properly, effective SSR can lead to a professional, diverse military that respects civilian authority. Emile Ouédraogo, a parliamentarian in the National Assembly of Burkina Faso and with ECOWAS, wrote in “Advancing Military Professionalism in Africa” that military professionalism is grounded in “the subordination of the military to democratic civilian authority, allegiance to the state and a commitment to political neutrality, and an ethical institutional culture.”

Perhaps no nation exemplifies that professional military ideal better than Senegal. Through its Armée-Nation model, the military has committed to safeguarding peace, protecting the people, and assisting in social and economic development. That commitment has lasted 54 years, as Senegal has never had a coup and always transferred power peacefully.

Botswana, Cape Verde, Mozambique, Namibia, Zambia and a few others are among a small group of African countries whose governments have never been toppled by a military coup.

Coups, such as those in Guinea-Bissau and elsewhere, have a cumulative negative effect on a nation’s chance for stability. “Once the precedent of a coup has been established, the probability of subsequent coups rises dramatically,” Ouédraogo writes. “In fact, while 65 percent of Sub-Saharan countries have experienced a coup, 42 percent have experienced multiple coups. … In contrast, non-resource rich states that have realized the highest levels of sustained growth are almost uniformly those with few or no coups.”

Ultimately, SSR acknowledges that citizens have a right to have a say in their security, N’Diaye said. It involves those who have been excluded — whether due to region, ethnicity or gender — and it empowers them.

Countries that do not carry out SSR are likely to continue excluding citizens and putting the security of the regime ahead of the security of citizens. That is not sustainable, N’Diaye said, and will lead to continued conflict and instability. “So that is the price that countries that do not carry out SSR will pay one day or the other.”

Security Sector Reform

1 Approach: Local Ownership

2 Objectives: Effectiveness, Accountability

3 Dimensions: Political, Holistic, Technical

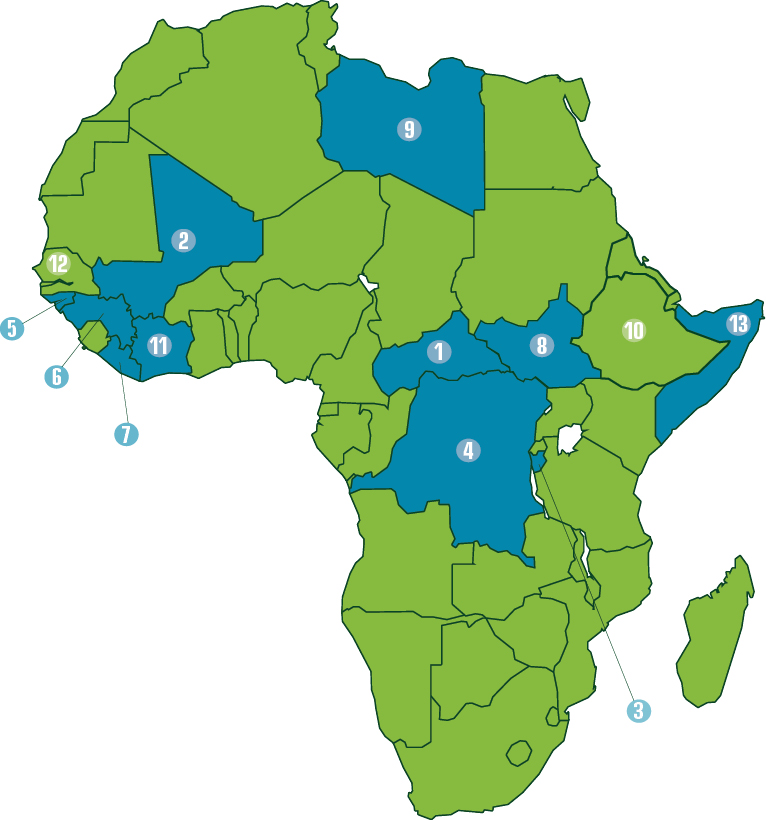

Security Sector Reform in Africa

ADF STAFF

Security sector reform (SSR) typically gets underway once a conflict has ended. The United Nations’ Department of Peacekeeping Operations’ SSR unit has in recent years started supporting the process at every level, typically through U.N. peacekeeping missions. Those missions, each of which has an SSR component, are represented on the accompanying map.

The U.N. also offers assistance through the United Nations Office to the African Union in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, and the United Nations Office for West Africa in Dakar, Senegal. The United Nations Assistance Mission in Somalia advises the government and the African Union Mission in Somalia on various issues, including SSR and disengaging combatants.

The African Union also has joined the SSR effort. In January 2013, the AU adopted its “Policy Framework on Security Sector Reform,” which seeks to establish objectives and principles for SSR in Africa, and offer Regional Economic Communities, member states and other actors guidelines for starting SSR programs. Other objectives include providing training and capacity building, and guiding partnerships between continental and international organizations.

Boubacar N’Diaye, chairman of the African Security Sector Network (ASSN) said the AU has been encouraging nations to embrace SSR. “I have just returned from the CAR, where our mission was led by the AU to assess the needs for SSR of that country,” he said. The European Union, the ASSN and the U.N. are helping the AU improve its ability to follow through with implementing its new policy framework, N’Diaye said.

The U.N.’s Department of Peacekeeping Operations’ SSR unit supports field missions that assist national and regional SSR efforts by:

- Facilitating national dialogues

- Developing national security policies, strategies and plans

- Strengthening oversight, management and coordination

- Articulating security sector legislation

- Mobilizing resources for SSR-related projects

- Harmonizing international support for SSR

- Providing education, training and institutional building

- Monitoring and evaluating programs and results

- Undertaking defense sector reform

Legend

- United Nations Multi-dimensional Integrated Stabilization Mission in the Central African Republic

- United Nations Multi-dimensional Integrated Stabilization Mission in Mali

- United Nations Office in Burundi

- United Nations Organization Stabilization Mission in the Democratic Republic of the Congo

- United Nations Integrated Peace-building Office in Guinea-Bissau

- SSR is underway in Guinea (Conakry) through the United Nations Development Programme.

- United Nations Mission in Liberia

- United Nations Mission in the Republic of South Sudan

- United Nations Support Mission in Libya

- United Nations Office to the African Union (The office is in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, but no SSR is ongoing in that country.)

- United Nations Operation in Côte d’Ivoire

- United Nations Office for West Africa (The office is in Dakar, Senegal, but no SSR is ongoing in that country.)

- United Nations Assistance Mission in Somalia