Disease Outbreaks Can Quickly Overwhelm Resources, So Strengthening Military and Civilian Ties is Key

ADF STAFF

The disease, which began on a farm in Jaji, Nigeria, was a virulent strain of bird flu known as H5N1. Its casualties were chickens. Birds not killed by the infection were slaughtered to prevent the flu’s spread.

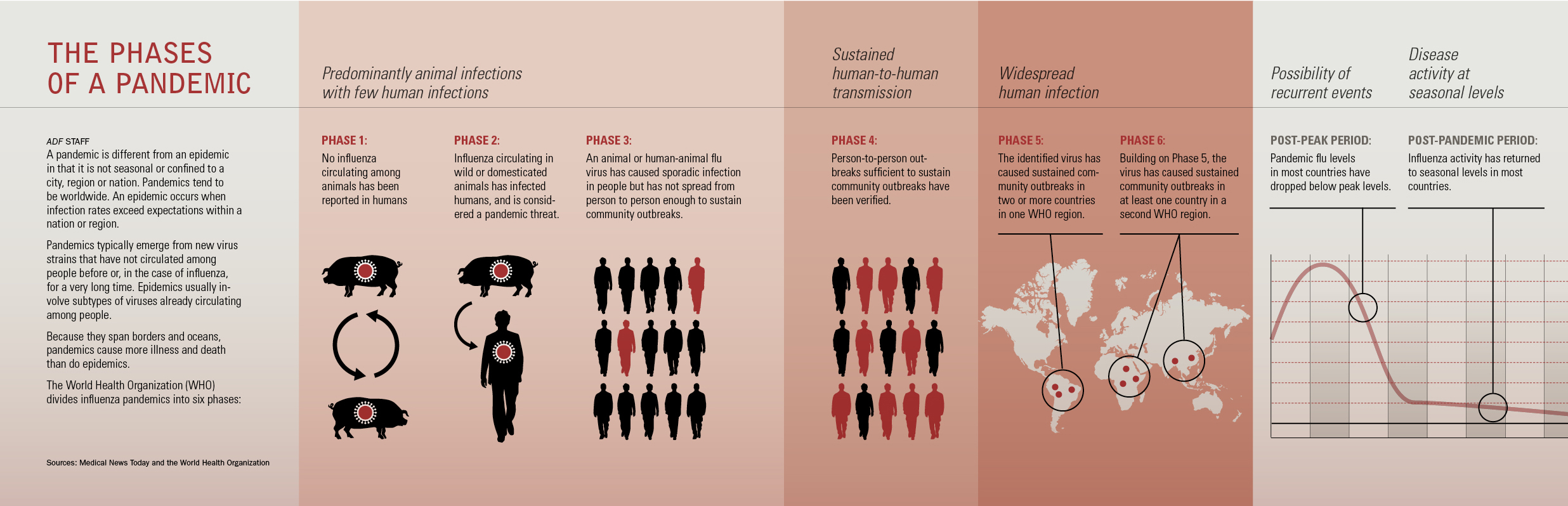

Now, imagine the same scenario, but this time the victims are people. The result is a pandemic flu with the power to spread from country to country, across the continent and all over the world. Hundreds of millions could become sick, and millions could die. The threat is not hypothetical. Every few years, another influenza strain emerges, and with it the possibility of a global pandemic.

In 2013, the H7N9 strain killed nearly 40 people in China by July, according to the journal Nature. “H7N9 viruses have several features typically associated with human influenza viruses and therefore possess pandemic potential and need to be monitored closely,” said Yoshihiro Kawaoka, an avian flu expert at the University of Wisconsin-Madison in the United States. “If H7N9 viruses acquire the ability to transmit efficiently from person to person, a worldwide outbreak is almost certain since humans lack protective immune responses to these types of viruses.”

Complicating matters is the fact that H7N9 is not fatal to poultry. This erases an important signal that a virus is present, making it more difficult to detect and fight. As of July 2013, the virus was killing more than 20 percent of those it infected, a proportion that makes a global outbreak all the more terrifying.

A devastating pandemic has happened before. In 1918, the so-called Spanish flu killed 50 million people worldwide, more than any other illness in recorded history. A fifth of the world’s population contracted the virus, and most of its victims were between 20 and 40 years old. In the United States alone, an estimated 675,000 died of the flu. Some victims died the same day they showed symptoms.

Planning a Response

Planning a Response

Preparedness is essential when a disease has the potential to spread like the 1918 flu pandemic. Many flu strains originate in East and Southeast Asia, then spread around the globe. It is thought that flu viruses incubate in the region because cities there are densely populated and well-connected. Once a virus reaches Africa, the potential for rapid spreading intensifies because of cross-border travel, trade and the limited capacities of many African health care systems.

To address these concerns, in 2008, the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) worked with the Office of the Secretary of Defense to start the Pandemic Response Program (PRP) in Africa and the Asia-Pacific region. The goal was to focus on the military’s role to support civil authorities if a severe pandemic occurred, said Erik Threet, PRP manager for U.S. Africa Command.

The program has had regional meetings on the continent to familiarize African nations with the plan. It’s up to individual nations to invite U.S. Africa Command officials to be a part of their planning. Officials in Benin, Burkina Faso, Ghana, Kenya, Liberia, Nigeria, Senegal, Tanzania, Togo and Uganda have worked with U.S. officials to form plans to deal with pandemics, Threet said.

Awareness Is Key

When Daniel Gambo, director of Nigeria’s National Emergency Management Agency, attended a pandemic response exercise in Tanzania as an observer, his country already had drafted a pandemic response plan but had never used it, he told ADF. Instead of waiting for an outbreak, Nigerian officials decided to test the plan.

Nigeria sent U.S. Africa Command its plan, and a tabletop exercise was held in October 2011 in Lagos. “It has been wonderful because we, for the exercise we did, we had 100 participants cutting across all the agencies that have to do with pandemic disaster,” Gambo said. “This created a lot of awareness.”

A few months later, officials looked at the lessons learned during the exercise. Military officials attended that meeting so a military contingency plan on pandemic response could be developed.

Later, officials compared civilian and military plans, and another meeting and exercise was held in November 2013 to go over three final plans: the Federal Republic of Nigeria’s Pandemic Preparedness and Response Plan; the Armed Forces of Nigeria Pandemic Contingency Plan; and the Military Assistance to Civil Authorities Disaster Contingency Plan, according to News Afrique Informations. The latest exercise will help officials develop a five-year strategic work plan for effective response.

Awareness is a primary goal of the program, said Lorraine Rapp, who co-manages U.S. Africa Command’s Disaster Preparedness Program with Threet. Despite planning with various nations, none has yet had to respond to a real-life pandemic. Still, the program has provided real benefits.

“It has more been about the work, the interaction, the fact that organizations and ministries that did not talk beforehand or felt that, ‘Oh, that pandemic is a health issue; we don’t need to deal with it,’ now have a better understanding that they do need to work together,” Rapp said.

Uganda benefited from that heightened awareness and communication during 2010 mudslides that killed 100 to 300 people in the Bududa district in the east. Pandemic response training, which brought together civilian and military officials, broke down barriers and reinforced the notion that pandemics are not just a health issue.

“We actually got feedback from one of their emergency management folks that because of the work they had done working under the Pandemic Response Program, they knew who their counterparts were in the military and felt comfortable calling them for assistance, whereas before they would not have had that,” Rapp said.

Exercises bring together more than just national government officials. Observers from other nations attend, as do nongovernmental organizations and United Nations agencies. Gambo has attended meetings in Ghana, Senegal, Tanzania and Togo. Likewise, Nigeria has invited representatives from Angola, Burkina Faso, Ghana and Mozambique to participate as observers or facilitators. “It helped us to know where we should be going,” Gambo said. “It also helped them to know where they are and where they hope to be. We are now taking the lead, and that is something of pride for Nigeria.”

The Military’s Role

Disease outbreaks usually begin as concerns for national ministries of health, but when a pandemic develops, the entire government must be involved. Threet said the focus of the PRP always has been “on what the military would do in support of civil authorities in the event of a severe pandemic.” With a virulent disease outbreak, thousands of people could miss work, and that could lead to the shutdown of critical infrastructure and commerce. Civilian health systems could be overrun, so the military could be called in to offer security and preserve order. “So we took it from that approach, from a security and stability issue as a result of a health initiative,” he said.

Kenya has completed its engagement through the PRP process. Retired Col. Vincent Anami, Kenya’s former director of the National Disaster Operations Centre, said training and exercises exposed gaps in the nation’s response capabilities. The nation had plans for medical responses, but it lacked the “whole-of-government approach” that the program encouraged. The new approach involves government, military and the private sector, but it focuses on military cooperation with civil authorities.

“The Kenyan military role, basically, is to support the civil authority in the medical aspect, in the logistic aspects and in provision of security during a pandemic,” Anami said. “So when it comes to medical, the doctors in the military will work in coordination and cooperation with the civil hospitals, they will provide facilities for when the civil hospitals are overwhelmed. … They will also provide logistical support where the civilian resources are overwhelmed during a pandemic.”

Not Just for Influenza

Before it was folded into U.S. Africa Command’s Disaster Preparedness Program, the PRP was set up to address major flu pandemics. But Rapp said pandemic training and planning also can equip nations to deal with other dangerous outbreaks.

Central Africa has been home to several outbreaks of Ebola, one of the world’s deadliest and most contagious viruses. Outbreaks have hit Côte d’Ivoire, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Sudan and Uganda. The virus takes its name from a river in the DRC. The Marburg virus is related to Ebola, and it also has caused outbreaks in Central Africa.

HIV/AIDS is still common on the continent, despite recent success in curbing infection and death rates. Africa also is home to the “meningitis belt,” which stretches from Eritrea in the east to Senegal in the west. Cholera outbreaks can occur when floods compromise clean water supplies, and polio has appeared recently in Somalia and Nigeria.

Any of these diseases could present a problem if they broke out in a camp for people displaced by drought, famine or floods. When that happens, having an effective plan that integrates the military’s unique response and logistic capabilities will be essential.

“For rapidly emerging threats, I think much of the training and planning is the same,” Rapp said.