Understanding the Cycles of Emergency Management Can Lessen the Impact of Disasters

ADF STAFF

With help from the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID), Malawians are learning conservation techniques to get the most from their land. They plant trees to hold water in the soil. They dig trenches to direct water to crops. Foot pumps also help move water. This work accentuates more traditional efforts to weather dry spells.

“We observe the behavior of birds, direction of the wind, or flowering of mango trees,” Jailos Mbawa, a Malawian community disaster risk reduction volunteer, said in a video for ProVention Consortium. “And we can tell if the rains will come or not.”

The efforts point to the importance of resilience, a crucial element of dealing with disaster. Resilient communities will diversify their means of livelihood to withstand shocks and stressors. A village that faces persistent droughts might not be able to rely on farming for sustenance. Its residents may raise goats and fowl to sustain them when crops are thin.

Government and military institutions also can foster resilience. National authorities must have frameworks and institutions that allow them to respond to disasters promptly and effectively. Understanding the cyclical nature of disasters, and the responses to them, can help build that capacity.

The Emergency Management Cycle Phases

The Emergency Management Cycle Phases

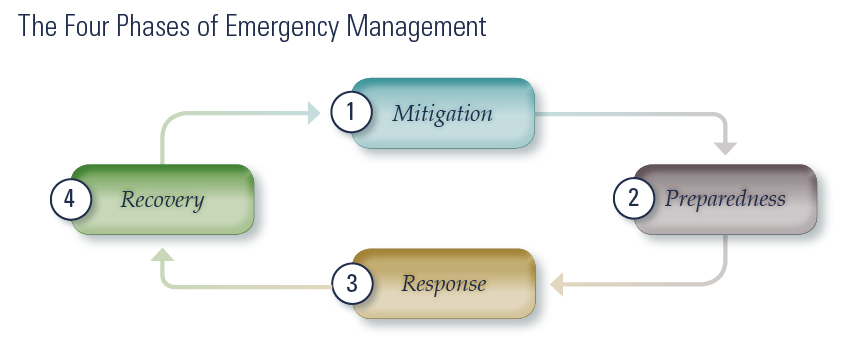

Just as many residents of southern Malawi have learned to adapt to the cyclical nature of droughts, national governments, militaries and emergency responders also have to know and plan around the emergency management cycle phases. These four phases are generally listed as: prevention and mitigation, preparedness, response and relief, and recovery and rehabilitation. The phases are typical of most major disasters such as floods and droughts, both of which are common in Africa. Here is a look at each phase:

Prevention and mitigation involve efforts to prevent future disasters, or at least to minimize their effects. It can include any act to reduce damage when disaster can’t be avoided. For example, in a farming village in Burkina Faso, residents try to head off the devastation from droughts with a dam that allows precious water to accumulate. Water is then directed to crops through small canals. Some farmers there and in Niger also are planting trees and digging demi-lunes (French for half-moons), semicircular indentations to capture and store water. These measures ensure irrigation when rain is scarce.

Preparedness entails planning that ensures safety and helps response and rescue operations. In late summer 2013 in Ghana, the National Disaster Management Organisation (NADMO) dealt with flooding, a common problem during the rainy season. Neighboring Burkina Faso was contemplating spilling water from its Bagre Dam to disperse its own heavy rainfall. Water from that spill was expected to flow into northern Ghana. To prepare for that possibility, NADMO National Coordinator Kofi Portuphy said that officials had mapped smaller waterways connected to the Volta River to identify vulnerable communities for evacuation if necessary.

Response and relief involve action to save lives and prevent further property damage. It’s at this time that preparedness and contingency plans are put into action. For example, in the event of a pandemic flu outbreak, a national health ministry could mobilize a vaccination program to slow the spread of infection. Militaries can help build quarantine areas and provide security so medical responders can treat and care for the sick. During famines, such as the one in Somalia from 2010 to 2012, security forces can ensure order as relief organizations distribute food.

Building Capacity Across the Continent

African nations’ ability to effectively prevent, respond to and recover from natural disasters varies widely, according to Lorraine Rapp, Disaster Preparedness Program manager with U.S. Africa Command. Her program engages willing African nations’ civil and military sectors, analyzing their emergency management systems to identify gaps and strengths. After that, the program offers workshops and training exercises to help build a plan of action so nations can set up their own disaster management systems. Once planning is done, stakeholders meet with U.S. Africa Command to see how it can help the nation build its capacity.

“I think that there’s a lot of capability, in that the folks that we work with, they’re professionals; they know what needs to be done,” Rapp said. “They have the right ideas. They just don’t have the resources to build that capacity.”

The command has worked most extensively with Ghana, Kenya, Nigeria and Uganda. It has had varying levels of interaction with Benin, Burkina Faso, Liberia, Mozambique, Rwanda, Senegal, Tanzania and Togo. Sideline support has been offered to Botswana, Mauritius and Morocco.

A Success Story in Ghana

Ghana stands out in Africa because of NADMO’s legal authority to coordinate disaster response among various national agencies. Other countries may have disaster management agencies, but without legal authority, they must work through their nation’s president or prime minister. This lack of authority can complicate and delay effective, coordinated responses when disaster strikes. In Ghana, NADMO is empowered through the Ministry of the Interior to coordinate responses.

Ghana also partners with the North Dakota National Guard (NDNG) through the U.S. Department of Defense’s State Partnership Program (SPP), which pairs U.S. states with countries around the world. Through that relationship, NADMO’s Portuphy has visited North Dakota to see the National Guard respond to flooding, a condition that both areas share. Maj. Brock Larson, North Dakota’s SPP director, said Portuphy returned home and soon began work constructing Ghana’s National Emergency Operations Centre. NDNG personnel helped the Ghanaians organize the center, set up information management, and trained instructors so that Ghana could train its own emergency management officials throughout the country.

Military Plays a Crucial Role in Disaster Response

When it comes to the four phases of emergency management, the military often can have the most impact in response and relief. Militaries have the equipment and ability to deliver food and other supplies, and set up communications, said Marcus Oxley, director of the Global Network of Civil Society Organisations for Disaster Reduction. Militaries can get people and equipment into areas hit by disaster, even if an event damages or destroys infrastructure.

That capability was evident early in 2013 when the South African National Defence Force (SANDF) helped Mozambique during floods that displaced thousands of people. The South African Air Force airlifted more than 150 tons of food, and SANDF rescued hundreds of people from the rising water of the Limpopo River.

Oxley’s group focuses on mitigation and prevention. Part of that is making sure people build resilience into their livelihoods, like the villagers in southern Malawi. Without progress in those areas, vulnerabilities will persist and communities will have trouble when disaster strikes. “So of course, we’ve got to have better preparedness, of course have better response, but unless we get to grips with the causes, then we’ll always be lagging behind,” Oxley said. “And unfortunately, that’s where the least progress is being made.”

It’s not uncommon for disasters to occur in conflict areas, such as the famine in Somalia. “It’s never just a natural disaster,” Oxley said. “It’s always an extreme vulnerability, extreme exposure, which as much is caused by the insecurity and fragility of those countries as it is to the natural phenomena itself — the cyclone, the flood, the drought. So you’ve got this kind of hybrid, if you like, in an African context — not always, but there’s a high likelihood that it’s going to be a hybrid of natural and man-made issues.”

Those man-made issues often involve a lack of security. So militaries can play a role before disaster strikes by fostering stability and ensuring security. “You’re never going to be able to build a level of resiliency unless you actually have a stable environment,” Oxley said.