When South Korea faced a communist incursion from the North in 1950, it asked the world for help. One country in Africa answered the call: Ethiopia.

Emperor Haile Selassie formed a battalion from his Imperial Bodyguard and deployed it to fight under the United Nations flag.

By the time the conflict was over, Ethiopia’s Kagnew Battalion had won the respect of allies and enemies. The Soldiers’ heroism during an outnumbered battle on “Pork Chop Hill” has become the stuff of legends. In fact, Ethiopia was said to be the only contingent that never lost a prisoner or left a dead comrade on the battlefield.

“We were the best fighters. The three Ethiopian battalions fought 253 battles, and no Ethiopian Soldier was taken prisoner in the Korean War,” combat veteran Mamo Habtewold told the BBC. “That was our Ethiopian motto: ‘Never be captured on the war field.’”

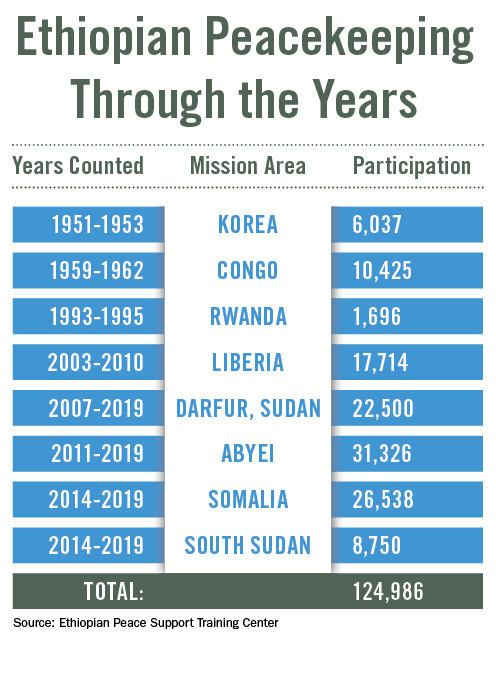

It was the beginning of a long tradition. Since that time Ethiopia has participated in 13 United Nations missions in countries ranging from Haiti to Yemen. Today, with more than 6,600 troops serving in four U.N. peacekeeping missions, Ethiopia is the largest contributor of uniformed personnel to U.N. missions in the world.

Nearly all of its U.N. peacekeepers are spread across three missions in Sudan and South Sudan, and 4,000 more troops serve in the African Union Mission in Somalia.

Ethiopia’s focus on neighboring nations is by design. Col. Elias Seyoum Abrha, commandant of Ethiopia’s Peace Support Training Center, said it comes from a long-standing national belief in “security interdependence.”

“Their security is intertwined with our security,” Elias said. “If there is something wrong with our neighbors, it affects us.”

Training Center Promises New Era

Despite this deep commitment to peacekeeping, until recently Ethiopian peacekeepers had limited access to pre-deployment and mission-specific training.

This changed in June 2015 with the opening of the Ethiopian Peace Support Training Center in Addis Ababa. The $6.2 million facility was partially financed by the United Kingdom and Japan. It is designed to offer training that elevates peacekeeping to a true military specialty and prepares personnel for the complexities and dangers of modern missions.

The center offers 28 functional and thematic courses on a range of topics including protection of civilians, conflict management, civil-military coordination and mediation. Since its inception, it has trained more than 6,300 people, including about 32% who travel from other African countries.

“We are open for all Africans, to share our experience,” Elias said.

The trainers from the center also operate the Hurso Contingent Training Center in a rural region of Ethiopia about 400 kilometers east of the capital. In this rugged camp, peacekeepers undergo predeployment classroom and field training that generally lasts about three months.

Hurso offers three modules: a generic course that fulfills the requirements of African Union or U.N. missions; special courses for skills such as logistics or combat medicine; and mission-specific courses designed to replicate the unique challenges of environments such as Somalia, South Sudan or Darfur. About 11,500 troops train in Hurso each year.

“In all missions we have a different package that they train on,” Elias said. “When we are discussing dynamic training, this is what it means: always adding and improving based on lessons learned.”

Having an Impact

Ethiopia’s domestic capacity for peacekeeping training is rare in Africa. In recent years, troop-contributing countries have had to compete for limited spaces in classrooms around the continent. Increasing training capacity in Africa has been a point of emphasis by the U.N., which wants to ramp up evaluation of troop performance during missions and offer troops continuing education.

“As we know, improved performance reduces fatalities,” U.N. Secretary-General Antonio Guterres said. “As such, training is a necessary and strategic investment in peacekeeping — and is a shared responsibility between member states and the secretariat.”

Ethiopia believes its investment in training is making a difference. In Darfur, the Ethiopian contingent was singled out by the force commander who lauded it for “going beyond mission tasks” and aiding the local population by drilling wells and mediating disputes. In Abyei, a disputed area claimed by Sudan and South Sudan, 1,900 Ethiopian peacekeepers received U.N. medals for gains made in the troubled region during an eight-month deployment.

Ethiopia also has increased the number of female peacekeepers to more than 600, a point of emphasis at the training center. The Ethiopian government has pledged to raise those numbers further. In 2016, Brig. Gen. Zewdu Kiros Gebrekidan was appointed deputy force commander of the United Nations Interim Security Force for Abyei, making her one of the few women ever to hold that command position.

Ethiopia’s military and civilian leaders say they intend to continue this dedication to peacekeeping for decades to come.

“Whatever problems we are faced with, we will realize peace and security, even if we have to sacrifice our own lives,” said Capt. Gabrhiwot Gebru, deputy commander of the Ethiopian Battalion in the U.N. Mission in South Sudan.

“Whatever problems we are faced with, we will realize peace and security, even if we have to sacrifice our own lives,” said Capt. Gabrhiwot Gebru, deputy commander of the Ethiopian Battalion in the U.N. Mission in South Sudan.