BY CYRIL ZENDA

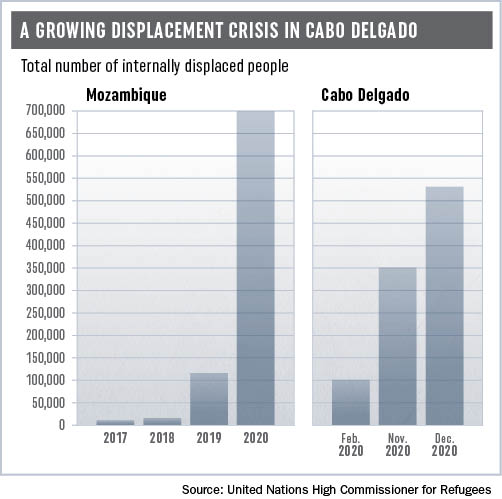

A ruthless and shadowy insurgent group has taken root in northern Mozambique’s Cabo Delgado province. The Islamic State-aligned militants, known as Ansar al-Sunna — “supporters of the tradition” — emerged in October 2017 and have fomented violence that had killed more than 2,500 and displaced more than 700,000 as of mid-March 2021.

Cabo Delgado, located on Mozambique’s northern border with Tanzania, is home to about 2.3 million people, 60% of whom are Muslims. Locals know it as “Cabo Esquecido,” or “Forgotten Cape.”

Since 2019, the Mozambican government has employed private military companies (PMCs) to help battle the insurgents, with mixed success. The groups are controversial and highlight the financial and human rights ramifications of outsourcing national security to private interests.

Furthermore, analysts say Mozambique’s reliance on high-cost PMCs in the province’s natural gas-rich northeast might be unsustainable in the long term.

“The stakes are extremely high,” said Lionel Dyck, head of the Dyck Advisory Group, a South African PMC that has helped the government put down the insurgency in Cabo Delgado. “But the Mozambique Defence Forces are unprepared and under-resourced, and we have to move fast,” he told the Africa Unauthorised website in July 2020.

Since the end of 2017, the national military has been trying to crush the armed group that has destabilized the region where ExxonMobil, Total and other international energy companies came in to capitalize on $60 billion in natural gas deposits.

ROOTS OF THE INSURGENCY

Just as the gas companies were laying groundwork, Ansar al-Sunna started its destructive insurgency. Locals call the group “al-Shabaab,” but it has no ties to the Somalia-based al-Qaida affiliate.

Although there is no consensus on the motives for the insurgency, analysts agree that religion might have provided a rallying point for those already dissatisfied with the widespread socioeconomic and political inequalities that have existed since Mozambique gained independence from Portugal in 1975. These conditions have attracted mostly young people to radical movements such as Ansar al-Sunna, which promises that its form of Islam will act as a remedy to corruption and rule by elites.

“We occupy [the towns] to show that the government of the day is unfair,” a militant said in a 2020 video, according to the BBC. “It humiliates the poor and gives the profit to the bosses.”

Dr. Eric Morier-Genoud, a Mozambican-born political scientist at Queen’s University in Belfast, Northern Ireland, links the insurgency to specific historical and social dynamics.

“The movement emerged within a particular religious, social and ethnic group known as the Mwani,” Morier-Genoud said. “They feel they have been marginalized for decades by migration into their area, a lack of economic development and their neighbors’ political clout.”

Lorenzo Macagno, who has researched Islam in Mozambique’s Nampula province, argued that insurgent violence in the adjacent Cabo Delgado province could be an expression of jihadist tensions that have marked Islam in Mozambique for decades.

“I found Islam in the province of Nampula to be hospitable and peaceful, but I know that it has also been marked by internal tensions and that now they are experiencing a jihadist extrapolation in Cabo Delgado,” said Macagno, associate professor of anthropology at the University of Paraná, Brazil.

For Macagno, poverty, state repression and the presence of foreign capital in natural gas projects are not enough to explain the armed uprising in Cabo Delgado. Those factors are present in other parts of Africa and the world, where there are no jihadist ventures.

The armed groups “present themselves as messianic and with an agenda for the salvation of an Islam which combats Muslims deemed apostates, who collaborate with the secular state,” he said.

President Filipe Nyusi’s government in Maputo labeled the armed rebellion as acts of banditry and deployed military forces in the hopes of quickly quashing the militants. But that response proved woefully inadequate.

Researchers from Observatório do Meio Rural (Rural Observatory) (OMR), a Mozambican nongovernmental organization, are not surprised that the military deployment failed. They say some members of the Armed Forces, who also suffer from government neglect, share grievances with the militants.

They say that at the start of the rebellion, ordinary citizens feared government forces more than they feared the insurgents.

“In fact the military on the ground complain of being underpaid and of problems of logistical supply,” OMR researchers said.

The military deployments also have angered communities. Some locals “complain of theft and extortion of money by the military,” the researchers said. “News reports and WhatsApp videos indicate the general feeling that the military is not adequately protecting populations by avoiding confrontation with insurgents.”

Mozambican Soldiers and police officers are among the lowest-paid government workers. This, combined with a critical lack of resources, has severely affected morale and created conditions ideal for corruption.

In mid-2019, when it became evident that Mozambique’s Defence Forces, known as Forças de Defesa e Segurança, had no capacity to deal with the insurgency, Nyusi turned to PMCs for help.

About 200 mercenaries from the Wagner Group, a PMC reportedly controlled by Yevgeny Prigozhin, a Russian businessman with close Kremlin links, landed secretly in Cabo Delgado in September 2019. The fact that Wagner secured the lucrative contract over a number of African-based PMCs with solid experience operating in the region highlights the opacity of such contracts.

Wagner’s lack of regional experience was costly. By November 2019, Wagner had hastily retreated from Cabo Delgado after suffering heavy losses, including some beheadings.

Emboldened by their victories against the better-equipped Russian forces, the insurgents launched more daring attacks in 2020.

This pushed the government in April 2020 to hire Dyck Advisory Group. Immediately there were reports of success, including the killing of 129 insurgents.

“Some of the atrocities committed are unlike anything I have seen before, and I’ve seen a lot of wars, in a lot of different places,” Dyck, a former colonel in the Zimbabwean military, told Africa Unauthorised in July 2020 when he detailed reports of mutilation of bodies and cannibalism. “Despite this barbarism, this enemy is organised, motivated and well equipped. If we don’t get on top of this, it’s going to spread south fast and that will be a catastrophe for the entire region.”

A Dyck company official said in a March 31, 2021, report that Mozambique was not extending the company’s contract. The announcement came after an Amnesty International report accused all parties in the conflict of committing human rights violations.

Mozambique also is said to have hired Paramount Group, a South Africa-based global aerospace and technology company. Although Paramount Group doesn’t supply personnel, it does provide armored vehicles, aircraft, unmanned aerial vehicles and naval vessels, and training for pilots, K9 officers and vehicle operators.

THE COST OF PMCS

The cost of the hired guns might never be known, but analysts say PMCs always are expensive.

“There is no doubt that the use of PMCs is highly controversial in a country such as Mozambique; a lack of transparency means that it is hard to assess quite how lucrative these contracts may be, but it is clear that private contractors are expensive, with some PMCs earning up to four times the U.S. military salary,” security expert Ben Simonson wrote for Global Risk Insights.

Revelations by other PMCs that missed out on the Mozambican contract when it was given to Wagner Group showed that at that time, they were charging monthly bills of up to $25,000 for each contractor on the ground, in addition to equipment and other logistical considerations.

If these sums are accurate, monthly payments to a PMC easily can surpass the salary bill of Mozambique’s entire 11,200-person Army, whose Soldiers are paid an average of $70 per month.

The huge private costs have raised questions of how Mozambique can sustain the expense in the long term, considering the drawn-out nature of jihadist insurgencies such as those waged by Boko Haram in West Africa and al-Shabaab in Somalia.

Calton Cadeado, a lecturer at Joaquim Chissano University in Maputo and a defense and security expert, blamed past policies for the current state of affairs.

“The Armed Forces, for political, economic and geopolitical reasons, were weakened,” Cadeado said. “Politically, various voices, especially from the donors’ side, employed cynical arguments grounded on liberal theory to impose poor investment in the Armed Forces.”

Now it is clear, he said, that not investing in the military was a mistake. “Today, modernizing the Armed Forces is undoubtedly a must.”

Simonson agreed that PMCs are coming in to plug a huge security gap that Mozambican forces have no capacity to fill.

“There is no doubt that the operational deficiencies within Mozambique’s security forces have meant the inevitable: heavy reliance on private contractors. Above all, something is always preferable to nothing, and in this case, the use of PMCs has prevented a very severe situation from getting any worse,” Simonson said. “The unfortunate truth is that war is big business, and where there is conflict, there are private military contractors who seek to reap the profits.”

NONMILITARY SOLUTIONS

While Nyusi and his government pursue military solutions to the insurgency, analysts say the use of nonmilitary means to end the conflict always should be considered.

“They need to constructively engage with issues of land ownership, begin to address sectarian tensions and avoid vexing Muslims in their security operations if they want to prevent the Islamist guerrillas from tapping into local grievances and gaining more ground,” Morier-Genoud said.

Cadeado said it was important for the government to address issues that fuel dissatisfaction among local populations. The government should invest in development at the local level and pay close attention to the youth bulge in areas affected by the insurgency, he added.

Mozambique’s post-independence civil war fought from 1977 to 1992 between the ruling Marxist-Leninist Front for the Liberation of Mozambique, known as FRELIMO, and insurgent forces of the Mozambican National Resistance, known as RENAMO, only ended through negotiations. This raises serious misgivings about the possibility of ending the current conflict through purely military means.

“The solution cannot be just military, because it’s almost impossible to win [against] a guerrilla movement in a scenario of poverty, inequality and with historical deep tensions,” OMR researchers warned. They added that private security forces don’t understand local dynamics or the forested terrain, which is complicated in an area where insurgents have some local support.

OUTSIDE HELP STARTS TO ARRIVE

The Mozambican government’s longtime hostility toward foreigners has not helped win outside assistance. It has been accused of cracking down on journalists, aid workers and opinion makers, some of whom have helped shed light on atrocities that have taken place in the conflict zone.

However, as the insurgency persisted, nations in the region and beyond began to consider various forms of assistance. As 2020 ended, Tanzania offered to conduct joint military operations along their common border, and Portugal offered to train members of the Mozambican Army.

In the spring of 2021, a dozen U.S. Army Green Berets began a two-month program to train Mozambican Marines in basic soldiering skills that could lead to more help, such as planning, logistics and combat casualty care, The New York Times reported. The U.S. also will consider providing intelligence help.

The South African National Defence Force in April 2021 sent in troops to provide logistical support for South African citizens wanting to return home, according to South Africa’s Eyewitness News.

In early May 2021, the European Union announced it would consider a military training mission in Mozambique, Reuters reported.

After months of deliberations, the 16-member Southern African Development Community (SADC) agreed on June 23, 2021, to deploy its regional standby force to help combat terrorism in Mozambique. Officials did not provide troop numbers, deployment schedules or personnel roles.

“This is just the first step to a wider solution,” Liesl Louw-Vaudran, senior researcher at the Institute for Security Studies, told Reuters. “This is the first time that … the SADC standby force has mobilized in a counterterrorism operation which is not peacekeeping. It’s a situation that’s very complex.”

Cyril Zenda is a journalist based in Harare, Zimbabwe. His work has appeared in Fair Planet, TRT World Magazine, The New Internationalist, Toward Freedom and SciDev.Net.

1 Comment

Great exposition about a burdensome conflict that few know existed. Thanks for the info