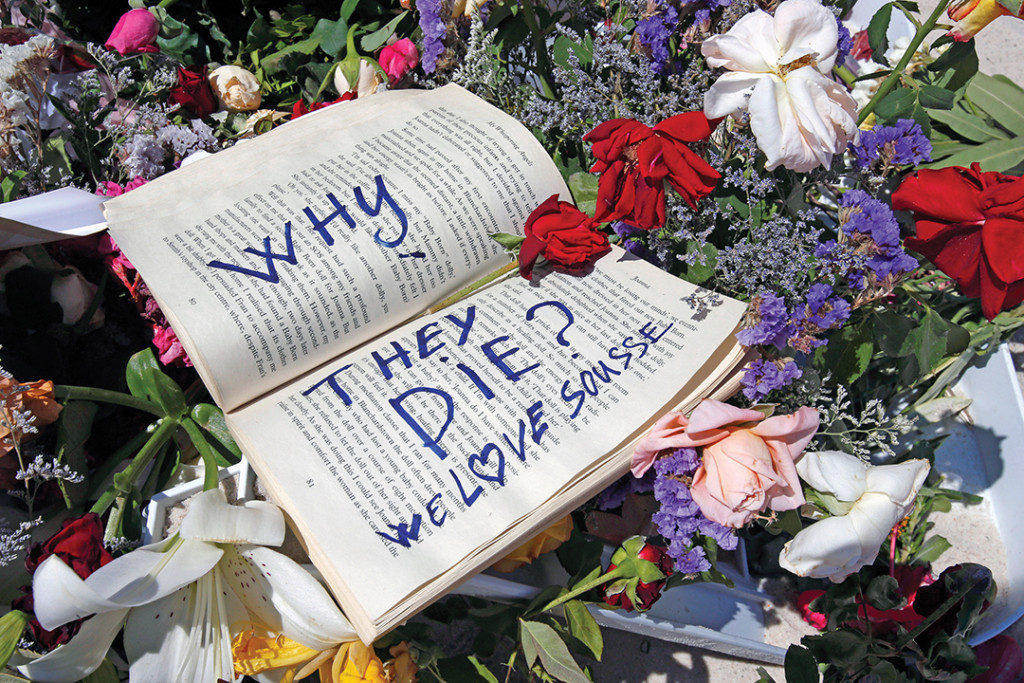

Tunisia was the birthplace of the Arab Spring and has long been held up as a model of stability and pluralism in volatile North Africa. But in 2015, a series of attacks sent shockwaves around the world. On March 18, 2015, three gunmen shot 22 people, most of them foreign tourists, at the Bardo National Museum in Tunis. Just three months later, a 23-year-old gunman opened fire at a beach resort near the city of Sousse, killing 38 vacationers. In November, a suicide attack against a military bus in the nation’s capital took the lives of 12 members of the presidential guard. In each case, ISIS quickly claimed responsibility.

The violence is symptomatic of a larger problem. An estimated 1,500 to 3,000 Tunisians have left home and traveled to Iraq or Syria to fight. That figure is the highest of any African country, and the phenomenon is causing some to worry that the promise of the Arab Spring will be snuffed out by extremists. “The Arab world is like a big forest, and in this forest Tunisia is the only flower of democracy,” resort worker Habib Daguib told The Guardian after the Sousse attack. “The terrorists want to cut this flower.”

Tunisian Minister of Defense Farhat Horchani took office in February 2015 and has made it a priority to steer young Tunisians away from terrorism. A lawyer by training who specialized in constitutional and international law, Horchani told ADF in a written statement that he firmly believes his country will return to peace. He pointed out that Tunisia has a long history of practicing moderate Islam and a tradition of multiculturalism dating back nearly 3,000 years to the time of the Carthaginians.

“Temperance is the hallmark of Tunisia’s ancient and contemporary history,” Horchani wrote. “It was known for its role in spreading the values of cooperation, solidarity, dialogue and peace in the whole Mediterranean basin.”

![Tunisian Minister of Defense Farhat Horchani [AFP/GETTY IMAGES]](https://adf-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/GettyImages-469897508.jpg)

Extremist preachers found a receptive audience in educated young Tunisians who were unable to find a job. According to the African Development Bank, the unemployment rate among the country’s young college graduates known as the “jeunes diplômés en chômage” generally hovers at 20 percent.

Horchani sees young people who are frustrated and aimless as a major threat to stability. “Joblessness, marginalization, poverty, and the absence of guidance and education are the reasons that young people are transformed into terrorists,” he wrote. “Extremists position themselves as the ‘saving cord’ from this disappointment.”

To reverse this trend, the Tunisian government has launched a number of initiatives. Mosques are being brought back under the supervision of the Ministry of Religious Affairs, imams who advocated violence have been removed, and a team of 600 officials is working to monitor religious extremism in the country’s mosques, Al-Monitor reported.

The country also is beginning to make progress militarily against ISIS affiliates. During 2014 and 2015, Soldiers located and cleared 79 terrorist encampments, the largest number of them in Mount Chaambi, near the country’s western border.

Horchani said Tunisia has been a victim of regional instability, most notably from Libya, which has lacked a central government since 2011. “It provides a fertile climate for the growth of terrorism and trafficking, which are two sides of the same coin,” he wrote.

To secure the border, Tunisia reinforced a natural land barrier between the two countries, using excavators to pile dirt and dig trenches filled with saltwater. Horchani said at the end of 2015 that the natural barrier was 87 percent complete, and the two nations’ shared border was secure and reinforced by electronic surveillance.

The military is continuing to emphasize professionalism, and Horchani noted that the institution gains credibility by being politically neutral and subordinate to civilian officials. “The power of the military stems from neutrality, patriotic belief and loyalty to the country,” he wrote.

As for the threat of terrorism, Horchani believes the nation needs a holistic approach that includes the military but also emphasizes education, democracy and responsiveness to social problems. “Fighting terrorism is a complete cultural project,” he wrote. He noted that the attacks on Tunisia have had a major impact on the nation’s tourism sector, which accounts for 14.5 percent of the nation’s gross domestic product, but the people of Tunisia remain unbowed.

“In spite of these operations and their negative impacts, life continues in our country in the economic, social and cultural domains,” he wrote. “Neighboring and partner countries are supporting us in countering terrorism and working to sensitize businessmen in investing in Tunisia and choosing it as a tourist destination. Despite these brutal attacks, terrorism cannot touch the unity of the state and its people.”