With Africa’s Internet Growth Comes More Risks and More Opportunity

ADF STAFF

The prospects for crippling cyber attacks are no longer the stuff of science fiction and blockbuster movies. The tools of cyber warfare have been tested on large and small scales all over the globe.

In short, cyber attacks are here to stay. Perhaps Ukraine offers the most effective and well-known example. It was there, in December 2016, that the lights went out. Hundreds of thousands of residents were plunged into darkness for hours until workers could manually re-engage the electricity grid. A similar attack had occurred a year earlier. The blackouts were not isolated incidents, but instead part of a stream of attacks, according to a June 2017 article in Wired magazine.

“They were part of a digital blitzkrieg that has pummeled Ukraine for the past three years — a sustained cyberassault unlike any the world has ever seen,” Wired reported. “A hacker army has systematically undermined practically every sector of Ukraine: media, finance, transportation, military, politics, energy. Wave after wave of intrusions have deleted data, destroyed computers, and in some cases paralyzed organizations’ most basic functions.”

Russia, increasingly famous worldwide for cyber mischief, is presumed to be responsible for the Ukrainian attacks.

In December 2016, Ukraine’s president, Petro Poroshenko, said there were 6,500 cyber attacks on 36 targets in the Ukraine in two months’ time. He blamed the attacks on the “direct or indirect involvement of secret services of Russia, which have unleashed a cyberwar against our country,” Wired reported.

Many observers see Russia’s apparent attacks on the Ukraine as a series of test runs. The nation could have gone further, caused more damage for longer, but it pulled back before it did irreparable harm.

“The gloves are off. This is a place where you can do your worst without retaliation or prosecution,” Kenneth Geers, a NATO ambassador who focuses on cyber security, told Wired. “Ukraine is not France or Germany. A lot of Americans can’t find it on a map, so you can practice there.”

THE THREAT IN AFRICA

At first glance, African nations might not seem to be likely cyber targets. But that is certain to change as connectivity across the continent increases.

Internet connectivity continues to hit milestones worldwide. More than half the world’s nearly 8 billion people — 51.2 percent — were expected to be using the internet by the end of 2018, the United Nations telecommunications agency announced that December. The figures also show that Africa experienced the strongest growth in internet access, going from about 2 percent in 2005 to more than 24 percent in 2018, the website Modern Diplomacy reported.

By 2022, 60 percent of the global economy is expected to be digitized, according to CNBCAfrica. And although those improvements can be a boon to development, increased connectivity will intensify opportunities for cyber crime. Cyber attacks lead to $400 billion in annual global economic losses. Malicious actors compromised more than 4.5 billion records in the first half of 2018, which was nearly double the 2.7 billion records compromised in all of 2017.

Dr. Greg Conti, security strategist at IronNet Cybersecurity in the United States, said there are two major types of cyber attacks: targeted and untargeted. In a targeted attack, cyber warriors might decide to compromise a particular nation’s energy sector or power grid, such as what happened in the Ukrainian attacks.

In an untargeted assault, cyber attackers might decide to indiscriminately go after dams all over the world. “If it’s easy, why not sweep us as much as you can? Find the vulnerable systems,” Conti said. Detecting vulnerabilities is not as difficult as it may sound. For example, a tool called Shodan, which a CNN report called “the scariest search engine on the internet,” looks for internet-connected devices 24/7, collecting information on 500 million services and devices each month.

Shodan turns up information on everything from the mundane — security cameras, traffic lights and home appliances — to the more sensitive, such as command-and-control systems for nuclear power plants. Many of these detected devices have no security measures, CNN reported.

“A quick search for ‘default password’ reveals countless printers, servers and system control devices that use ‘admin’ as their user name and ‘1234’ as their password,” CNN reported. “Many more connected systems require no credentials at all — all you need is a Web browser to connect to them.”

A security specialist used Shodan to find a car wash that could be turned on and off, CNN reported. A city’s entire internet-connected traffic control system could be put into test mode with a single command. So if it’s so easy to scan the entire internet for connected and vulnerable devices, it’s possible that African nations could get caught up in a wide-ranging, opportunistic attack.

“I have to think state actors, they plan ahead,” Conti told ADF. “If something’s easy, if it’s not that hard to do, I could see them sweeping Africa and countries that aren’t obvious power players in the world.”

Bad actors will prioritize regions, and Africa will not be ignored in that calculus. An October 2018 New York Times report indicated that Chinese and Russian spies have listened in on the personal conversations of world leaders. The communications systems of the heads of various military institutions in Africa also are valuable. So although such targets might not warrant the same level of effort by state-backed hackers, they would not be immune from attacks, Conti said.

AFRICA RESPONDS

Although cyber capabilities still need much growth and development, a number of African countries are showing increasing awareness and concern in the cyber security realm.

South Africa began an offensive strategy in 2016 and established a Cyber Security Incident Response Team “to prevent or recover from a cyber warfare incident through the establishment of the cyber command centre,” according to OIDA Strategic Intelligence, a French independent consulting firm. The team has been issuing periodic information security advisories and reports since at least October 2018.

Nigeria also is proactive in addressing cyber threats. The Nigerian Army has formed its Cyber Warfare Command, which reportedly will employ 150 people drawn from the military who are to be trained in information technology, according to a Forbes report. The command’s aim is to “monitor, defend and assault in cyberspace through distributed denial of service attacks on criminals, nation states and terrorists.” Nigeria has suffered numerous cyber attacks, including one blamed on insurgent group Boko Haram during the election in 2015 that hacked the Independent National Electoral Commission website.

Ghana’s Ministry of Communications has established the National Cyber Security Centre, which is charged with coordinating cyber security activities in government and the private sector. It also is responsible for cyber security incident coordination and awareness. The nation’s 2019 budget provides for the establishment of a National Cyber Security Authority to oversee protection of critical national information infrastructure, according to Myjoyonline.com.

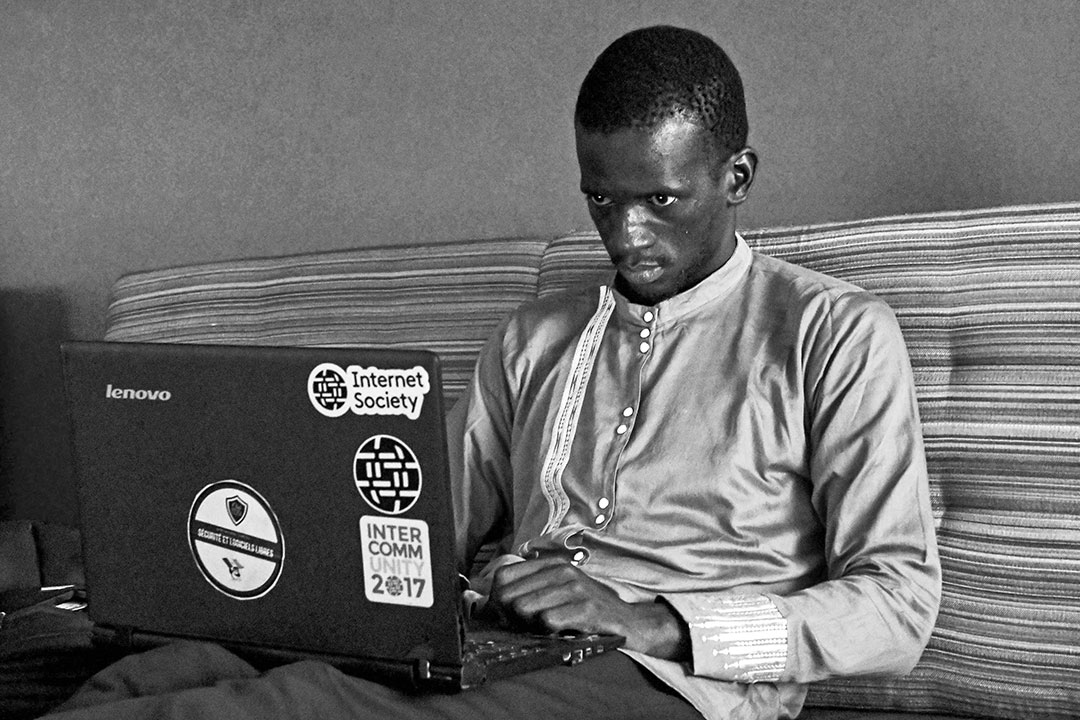

Senegal has set up the National Cyber-Security School to train security service, judiciary and business personnel in how to combat cyber crime such as terrorism funding and propaganda, Agence France-Presse reported.

More than 1,300 delegates from 28 African countries and beyond met for two days in Nairobi, Kenya, in July 2018 at the inaugural Africa Cyber Defence Summit. Attendees included representatives from government, business and academia across a wide range of industries and disciplines. According to ITWeb Africa, Mauritius’ minister of technology, communication and innovation, Yogida Sawmynaden, told assembled delegates that Africa needs a single cyber security law “to harmonize our laws and speak one digital language in order to counter attacks.”