Supplying Complex Peacekeeping Missions Is Complicated by Remoteness and Infrastructure Deficits

Any international peacekeeping mission will present a long list of logistical challenges. Mission settings are inevitably established in areas reeling from recent conflict, often rooted in age-old ethnic or political struggles.

Responding United Nations and African Union forces always are composed of international contingents. Sometimes dozens of countries from all over the world converge in a region, each bringing hundreds of Soldiers, police officers, supplies, weapons and vehicles.

Once in theater, forces must travel long distances, set up enormous camps and build field hospitals. Reliable supply chains require speed, efficiency and security. So many things can go wrong along the way: Deployments often are delayed, weather intervenes, violence erupts, and challenging terrain stands stubbornly immovable, forcing adjustments and workarounds.

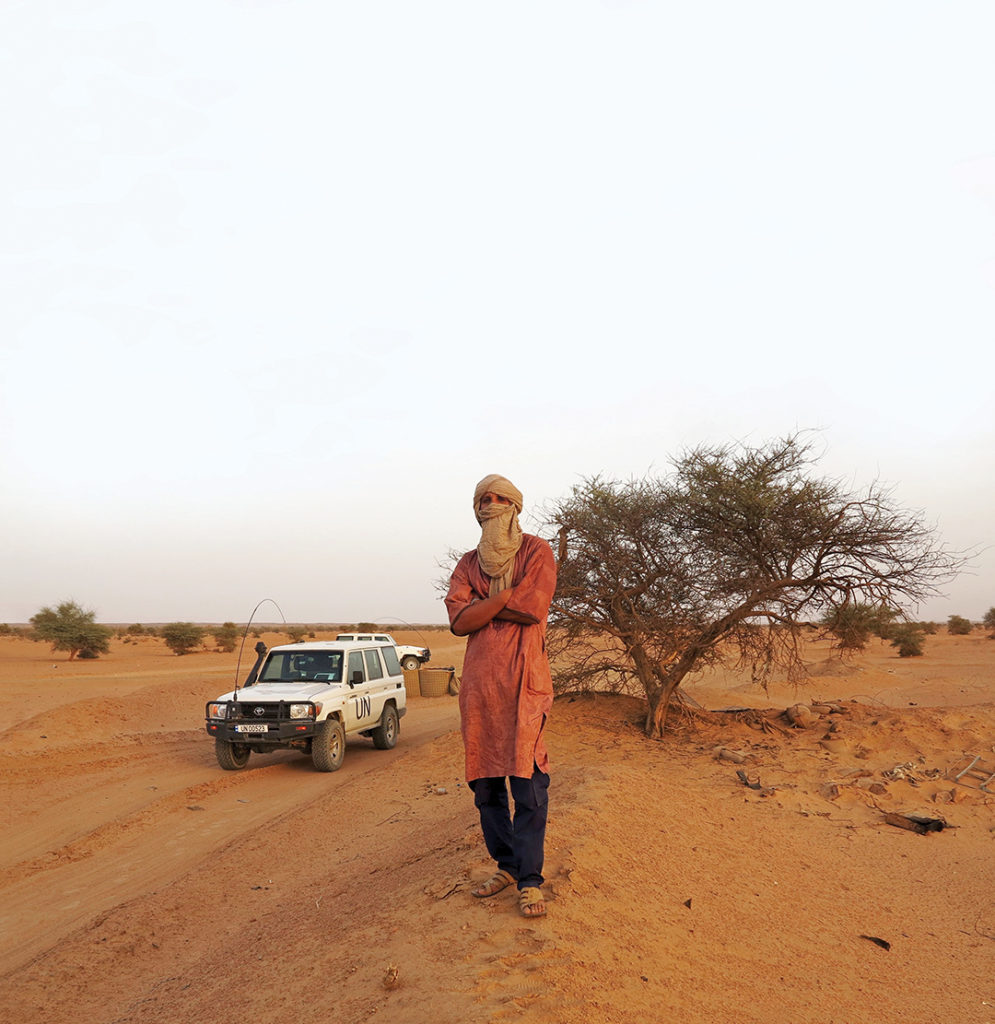

Each kilometer in the chain is one more little burden — a problem to solve, a condition to overcome. Nowhere is that more evident than in Mali.

In June 2013, Exercise Western Accord in Accra, Ghana, prepared commanders for the mission through a series of command-post scenarios at the Kofi Annan International Peacekeeping Training Centre. It was evident even then to one exercise participant that Mali would present profound challenges.

Nigerian Brig. Gen. Koko Essien, a veteran of peacekeeping missions in Burundi, Sierra Leone and the former Yugoslavia, considered the geography of Mali. His assessment to ADF at the time was brief and to the point: “It’s going to be a logistics nightmare in Mali.”

ALL THE WAY TO TIMBUKTU

Timbuktu at one time was an important trade hub and a repository of Islamic thought and scholarship. The ancient city of gold has long been synonymous with remoteness. Colloquially speaking, its name signifies the farthest reaches of the earth. But for forces serving in MINUSMA, the city’s remoteness takes on literal meaning.

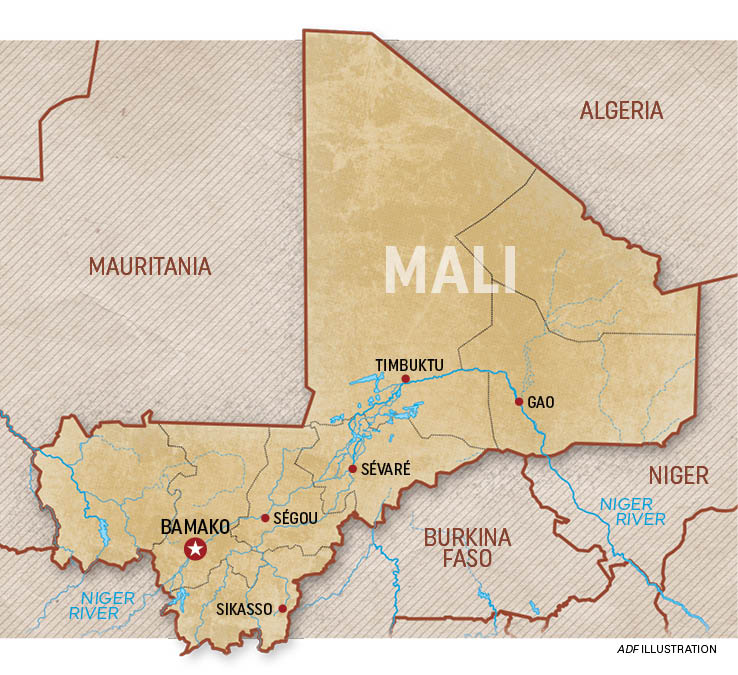

Like some of its neighbors — namely Algeria, Mauritania and Niger — Mali has a capital, Bamako, situated at one end of a vast expanse of territory where infrastructure, resources and governmental presence are concentrated. Travel from Bamako to Timbuktu and Gao, MINUSMA’s headquarters for Sector West and Sector East, respectively, is time-consuming and arduous, despite distances of just more than 1,000 kilometers. Both cities are roughly halfway between the capital and the northernmost border of the 1.2 million-square-kilometer nation. Saharan sand proliferates in the north, hills and granite rock formations cover the northeast, and savannas are prevalent in the south. The Niger River and other waterways cut through the middle of the country at its narrowest point, providing another layer of logistical challenges.

Essien was commander of Sector West in Timbuktu from August 2013 to August 2014. Just before he left, he commanded a quick-reaction force of 450 troops and three battalions of 850 each. A fourth battalion of 850 had been planned but had not yet arrived. He told ADF that while at Western Accord, he could not have imagined just how many logistical problems Mali would present.

“As a matter of fact, the statement — my thinking at the time was even better than what I met on the ground,” Essien said. “Because it was an absolute, absolute logistics nightmare. It was worse than I anticipated.”

“Overcoming Logistics Difficulties in Complex Peace Operations in Remote Areas,” a 2014 paper by Dr. Katharina P. Coleman of the University of British Columbia, lists some of the challenges of a mission such as MINUSMA.

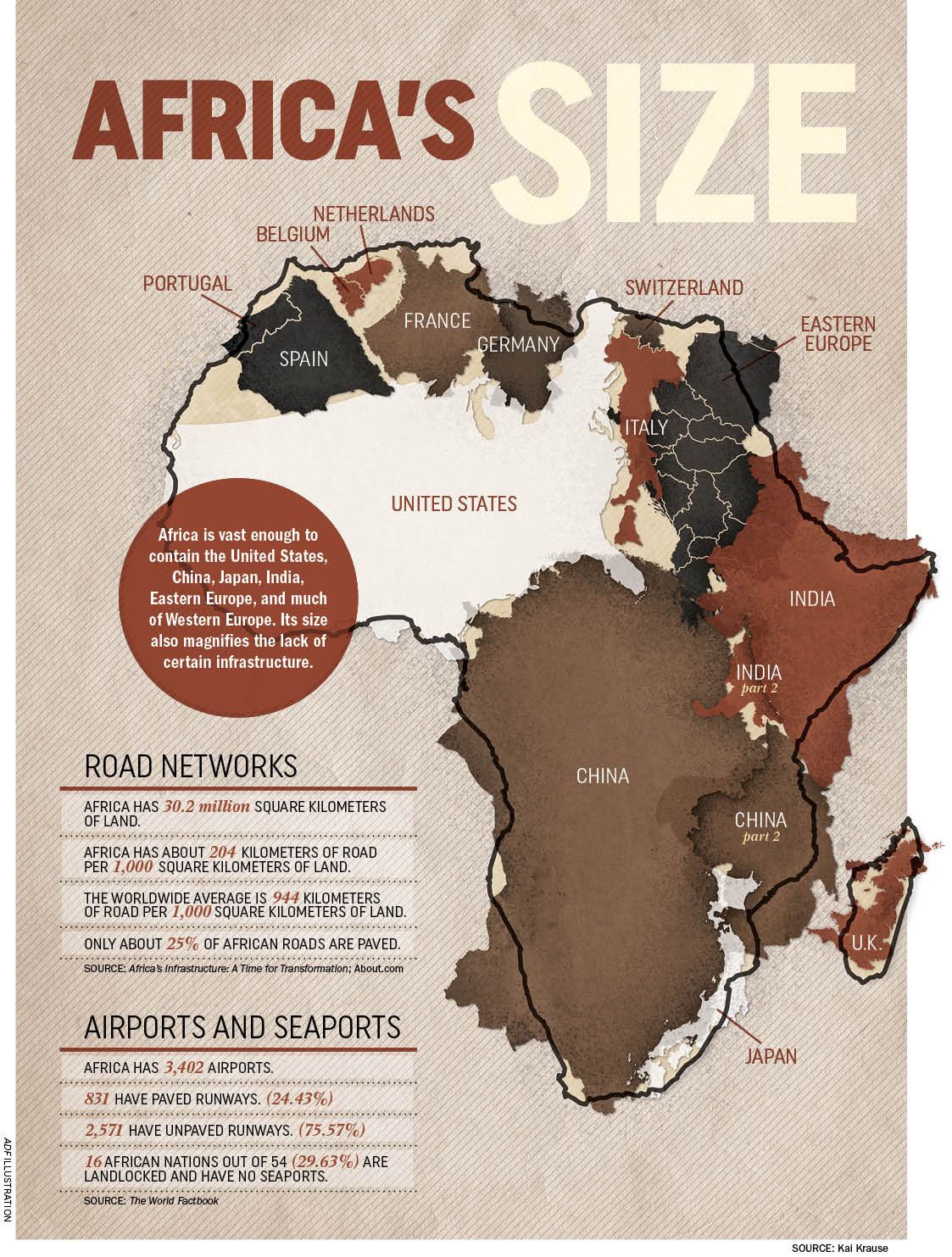

Mali, a landlocked country, embodies the problems of “external remoteness” and “internal remoteness.” Even before the first boots hit the ground in country, operation organizers must deal with the issue of how to deliver people, supplies and equipment without benefit of a seaport or a high number of large, well-equipped airports.

This external remoteness is time-consuming and expensive, Coleman writes, and can be subject to the political and bureaucratic caprices of surrounding nations when negotiating transit and over-flight consent.

Essien explained that only Bamako-Sénou International Airport in the capital is capable of accepting large commercial jets. That means that any cargo flown into Mali must be unloaded in Bamako and reloaded into trucks or smaller military transport planes, such as C-130s, to be taken into northern bases in Timbuktu and Gao. But that is only the first hurdle in dealing with internal remoteness. At this point, some of the biggest challenges are just beginning.

GETTING FROM POINT A TO POINT B IN MALI

Internal remoteness refers to the difficulty of accessing primary areas of operations within the mission’s host country. “Internally remote regions are often underdeveloped and under-served in terms of national infrastructure, so transport, communications and medical infrastructure may be scarce,” Coleman, an associate professor of political science, wrote. “Thus internal remoteness increases the operation’s need for air transportation assets, engineering units (including road construction and airfield engineers), and heavy transport companies, all of which the UN often struggles to secure from states (especially in a timely manner) and which are expensive to procure from contractors.”

As convoys got within 20 kilometers of Timbuktu, one major obstacle remained: crossing the Niger River. This required ferries, and each ferry could take only two to three trucks at a time. With convoys of up to 50 trucks, this stage alone could take up to five days. “Because these are not very sophisticated landing points, loading three trucks to the ferry takes a lot of time,” Essien said. “Offloading them on the other side takes a lot of time. So it’s been an absolute mess.”

“We had trucks that arrived within five to six days of departing Bamako,” he said. “And we had trucks that arrived after three weeks of departing Bamako.”

WORKING AROUND THE PROBLEMS

Essien and his forces found some ways to overcome logistical obstacles, despite infrastructure problems. One way was by working with local residents and depending on their advice on routes to take during inclement weather. Their guidance added a valuable dimension to more traditional global-positioning systems.

Coleman agrees that such civil engagement can be helpful, but she said such contact must be fostered carefully. “There’s certainly, I think, a clear argument that relations with the host populations are critically important to how a peace operation can function on the ground,” she told ADF. “The note of caution I think that I would simply sound there is that they need to be managed carefully to ensure that the peacekeepers do not — unbeknownst perhaps to themselves — wind up in relationships that are perceived as either not transparent or biased.”

Furthermore, peacekeeping forces must be careful about how they source things from local vendors, again to avoid bias and to ensure that they do not take away resources from local populations. An example would be a large military force locally procuring water or other items in a way that leads to shortages for residents.

“They followed the same routes, bringing their stuff without having to go by sea to Côte d’Ivoire and trucking them through Bamako,” he said. “For instance, when the Nigerians were setting up the Level 2 hospital, they got security clearance from all the countries between Nigeria and Mali, meaning Burkina Faso and Niger, and once they got the clearance, they put the trucks on the roads … and they came by road all the way from Nigeria to Timbuktu.” Their first major challenge was at the Niger River crossing.

Likewise, Essien said, the Togolese battalion moved its equipment through Togo into Niger, through Burkina Faso and on to Timbuktu.

On the issue of infrastructure, large military missions often face a two-sided challenge. First, they are forced to improvise around weak or nonexistent transit networks, such as ports, airports and roads. Then, even when roads exist, the heavy trucks, recovery vehicles and armored personnel carriers sometimes damage them. The Ghanaian military engineering company was able to perform some minor road repairs to keep vehicles moving in the area.

Essien served as deputy chief of military planning at U.N. headquarters in New York for four years. He said other peacekeeping missions, such as those in Sudan and the Democratic Republic of the Congo, and smaller missions such as those in Burundi, Côte d’Ivoire, Liberia and Sierra Leone, were easier to manage logistically because most of those nations have seaports and most do not have large deserts like Mali.

“I think Mali presented the U.N. with a logistics challenge that probably was unprecedented.”

Snapshot: MINUSMA

ADF STAFF

The United Nations Multidimensional Integrated Stabilization Mission in Mali (MINUSMA) began in the summer of 2013. Mali’s democratic government fell in a March 2012 coup just after a Tuareg rebellion had begun in the north.

Soon afterward, several factions, including the Tuareg National Movement for the Liberation of Azawad, Ansar al-Dine and al-Qaida in the Islamic Maghreb, began to wreak havoc, capturing cities and threatening to advance south toward the capital, Bamako.

French and Chadian forces intervened in January 2013 in Operation Serval, taking back the cities of Timbuktu and Gao. France began withdrawing troops in April 2013, and troops serving in the African-led International Support Mission in Mali, which had entered Mali in February, began supporting Malian forces.

AUTHORIZED STRENGTH

- 12,680 Total uniformed personnel

- 11,240 Military personnel, including 40 military observers

- 1,440 Police (including formed units)

Strength as of June 30, 2015

- 10,207 Total uniformed personnel

- 9,149 Military personnel

- 1,058 Police (including formed units)

COUNTRIES contributing military personnel

Bangladesh, Benin, Bhutan, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Burkina Faso, Cambodia, Cameroon, Chad, China, Côte d’Ivoire, Denmark, Djibouti, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Egypt, El Salvador, Estonia, Finland, France, The Gambia, Germany, Ghana, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Indonesia, Italy, Jordan, Kenya, Liberia, Madagascar, Mauritania, Nepal, Netherlands, Niger, Nigeria, Norway, Portugal, Romania, Rwanda, Senegal, Sierra Leone, Sweden, Switzerland, Togo, Tunisia, Turkey, United Kingdom, United States and Yemen.

COUNTRIES contributing police personnel

Benin, Burundi, Cameroon, Chad, Côte d’Ivoire, Djibouti, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, France, Germany, Ghana, Guinea, Jordan, Madagascar, Netherlands, Niger, Nigeria, Romania, Rwanda, Senegal, Sweden, Togo, Tunisia, Turkey and Yemen.