ADF STAFF

For most of post-independence history, air forces in Africa were not a priority. Expensive and difficult to maintain, air power was seen as a luxury not useful to the realities and unique threats on the continent. With tight budgets and command structures dominated by ground forces, air forces make up less than 10% of uniformed personnel in many countries.

That is changing. As countries face the threat of violent extremist organizations, light attack aircraft are proving to be a force multiplier that gives the military the upper hand. In battles against insurgent groups that thrive in remote areas, intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance capabilities are essential to launching targeted strikes. For countries seeking to move personnel, equipment or relief supplies to crisis regions, heavy airlift is the best solution.

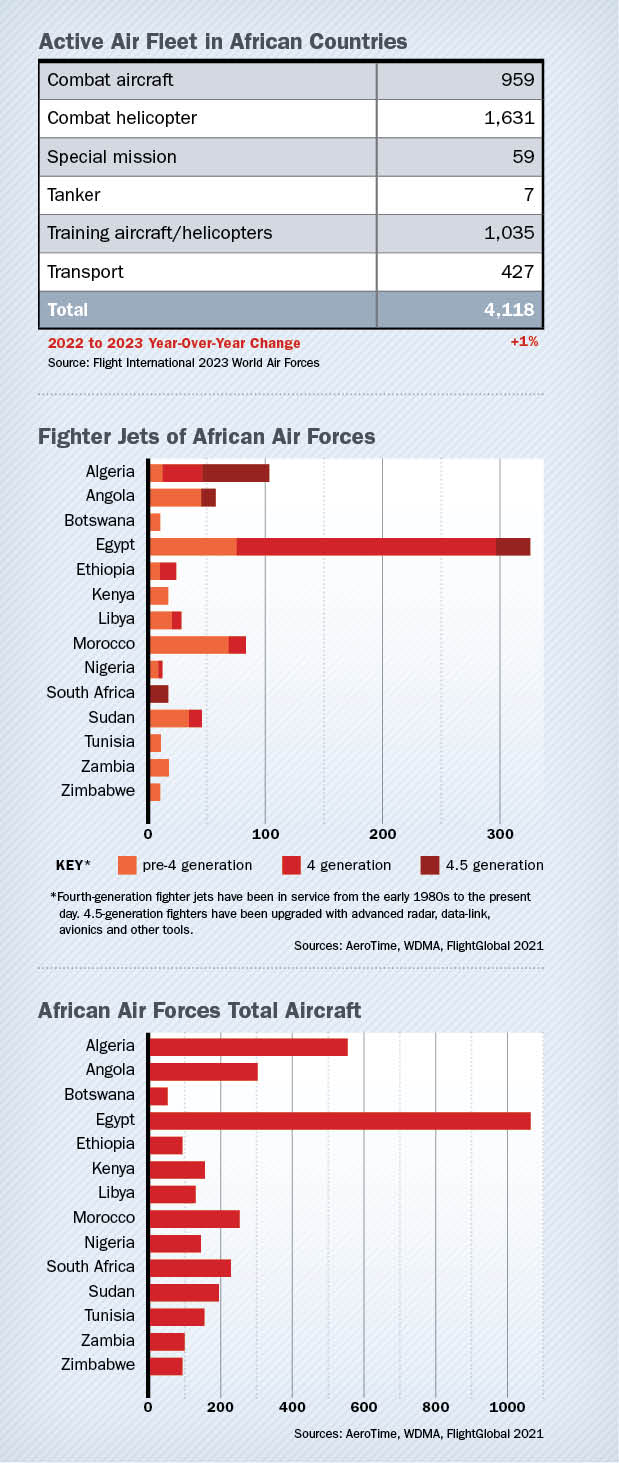

Between 2022 and 2023, Africa was one of only two regions in the world that saw a full percentage increase in its continental fleet size, adding 41 military aircraft. Large, well-established air forces increased their transport fleets. Algeria added two LM-100J transport aircraft, Tunisia ordered eight Beechcraft T-6C turboprop trainers, and Angola ordered three Airbus Defence and Space C295s for maritime surveillance and transport. Meanwhile, the Moroccan Air Force is expected to receive 25 F-16 Block 72 fighter aircraft between 2025 and 2027.

The reason for the investment is on-the-ground success. Maj. Gen. Abdul Khalifa Ibrahim, then-force commander of the Multinational Joint Task Force in the Lake Chad region, summed it up when he said air power is “central” to his troops’ ability to defeat violent extremist groups.

“In modern warfare, one of the dominant themes is the use of air power because it gives an additional reach; it allows delivery in places that ground troops can’t easily reach,” Ibrahim told ADF. “Air power has been a force multiplier of immense proportion.”

ISR Offers Eyes in the Sky

As air forces combat insurgencies that operate in some of the toughest and most isolated environments on the planet, the ability to track them from the air and plan a speedy response is crucial. The same principle applies to efforts to fight drug trafficking, piracy, illegal fishing and wildlife poaching.

Intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance (ISR) platforms are not simply aircraft, they are systems through which information is collected, processed and put in the hands of decision-makers. Therefore, the ability to collect information from the sky is only as valuable as the ability to “process, exploit and disseminate” it.

Most ISR aircraft are equipped with a high-definition camera and video recorder integrated with a mapping system. Aircraft with infrared capability can track vehicles or people through the night. Common models include the Beechcraft 350ER King Air, Cessna 208 Caravan and Diamond DA42. South Africa’s Paramount Group produced the two-person Mwari with hybrid ISR and close-air support capabilities. It bills itself as a rugged aircraft designed for austere environments that requires minimal logistical support.

There is a wide range of options. Some countries are buying refurbished planes that have been decommissioned by other air forces. Others are contracting with companies to conduct surveillance. Still others have found unmanned aerial vehicles to be a cost-effective solution.

“For countries with limited resources and finances for this role, there is no need for an expensive ‘all singing-all dancing system,’” according to Times Aerospace. “Today, there are several airborne non-traditional ISR (NTISR) options out there, which are relatively cheap, and can do the job.”

Light and Effective

African air forces are moving away from costly fighter jets that provide overwhelming firepower but are most useful for interstate conflict. Instead, countries are investing in small fixed- or rotary-wing aircraft equipped with attack capability in the form of guns or air-to-ground missiles.

These aircraft are cheaper, easier to maintain and better adapted to the threat of violent extremist organizations. One example of this is the Aero L-39, which is in service as a trainer or with ground-attack capability in 10 African countries, according to Times Aerospace. Other countries have opted for turboprop aircraft, with the A-29 Super Tucano among the most popular.

Light attack aircraft are no longer viewed as a consolation prize to a costly fighter jet. Many countries now see them as a better tool for asymmetric warfare.

“Though many African air forces have prioritized the procurement of fast-jet fighters, some have found themselves, either as a result of smart procurement practices, or because of historical accident or budgetary need, to have far more useful equipment,” according to Times Aerospace.

The countries that have developed ISR capabilities along with a fleet of light attack aircraft have shown the best results.

“African air forces require easy to maintain and operate light attack aircraft with acceptable flight hour costs,” wrote Stephen Burgess in “Africa Airpower: A Concept” published in Revista da UNIFA. “If an attack capability can be paired with an ISR capability on a common platform, the utility increases even further. This pairing of ISR and strike functions on an airframe significantly accelerates the kill chain, allowing an aircraft to target a [violent extremist organization] almost immediately after finding it.”

Strategic Lift Is a Shared Responsibility

Africa is one-fifth of the world’s landmass, and many of its nations face challenges of vast, lightly inhabited territory with underdeveloped road systems. In emergencies, it is essential to move personnel or supplies quickly to the place they’re needed most. Strategic airlift is needed for these peacekeeping efforts and humanitarian responses.

But the continent suffers from a shortfall in strategic airlift. Only a handful of countries have the assets necessary to transport troop contingents and heavy equipment over long distances in short periods, according to an analysis published by the Africa Center for Strategic Studies.

The largest platforms, with a maximum payload of about 75,000 kilograms, can transport enough equipment into an area of operations to support a full brigade. Medium-sized airlift platforms with a maximum payload of about 18,000 to 36,000 kilograms, are better suited to move equipment to support one to two battalions on short notice. These planes are costly to acquire, maintain and to train those who will operate them.

Since capabilities are unevenly distributed on the continent, experts believe there is a need to coordinate efforts. This could mean sharing resources or pooling funding to increase purchase power. It begins with transparency and documenting capabilities country by country to determine where strengths and shortfalls exist.

A Joint Approach

Regions around the world have shown that collaborating and sharing air resources in areas of mutual interest leads to success. Africa, like many parts of the world, faces challenges that impede cooperation. This includes a lack of equipment interoperability, training and force structure differences, language barriers, and mistrust.

Stephen Burgess, in “Africa Airpower: A Concept” published in Revista da UNIFA, writes that a good starting point for cooperation is the creation of regional training centers. Led by regional economic communities, countries could create pilot training programs and offer slots to each country in the region. There could be similar training centers for maintenance and other specialties. This builds a shared bond and a community of experts among Airmen in the region.

As air force partnerships develop, there could be opportunities for shared acquisition of new aircraft, standardizing equipment, joint training, and shared intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance data relating to common threats.

There is some movement in this direction. The African Union is creating an Africa Air Mobility Command Center, which would be a multinational airlift unit that shares continental resources to move personnel and equipment. Sharing strategic airlift will require common doctrine and procedures that could be a springboard to additional cooperation.

“We need to come up with mechanisms of optimizing the use of the very limited resources available to us,” said Botswana Defence Force Brig. Collen Mastercee Maruping, acting deputy air arm commander.