ADF STAFF

Sarah Downs jumped onto her Facebook page after South Africa’s government announced it would resume its COVID-19 vaccination campaign in late April after a two-week pause.

“Great news,” she posted. “Make sure you are signed up. If you have concerns, ask.”

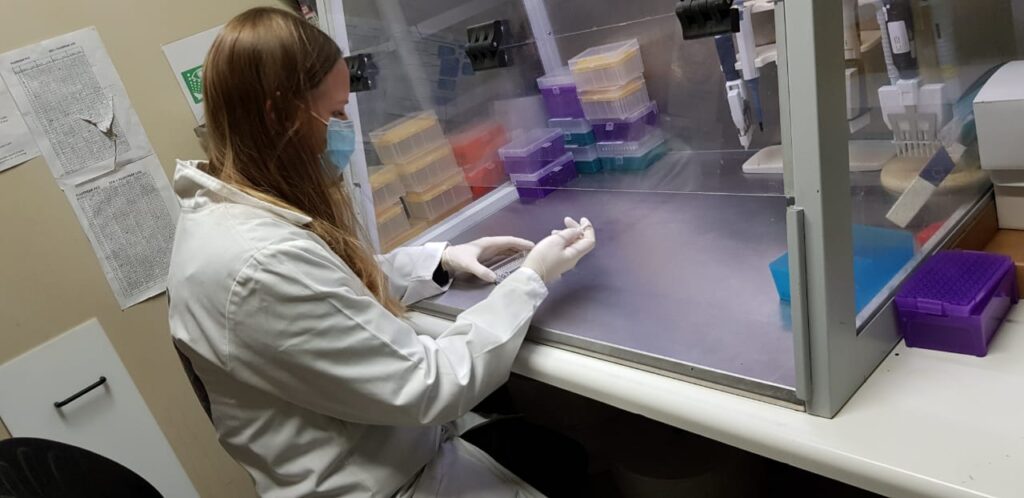

Based near Johannesburg, Downs is a scientist who is a couple of months from finishing her Ph.D. in infectious respiratory disease.

The 39-year-old doesn’t have a lot of free time to scroll through social media, but that’s where you’ll find her and a small army of volunteers fighting COVID-19 misinformation, diligently answering questions and debunking conspiracies while promoting science and media literacy.

“Just about every day I get a message from a friend or get drawn into a conversation about it [misinformation],” she told ADF.

Downs was invited to join a private Facebook group called Pro-Vaccination South Africa in 2016, when misinformation was spreading about a measles vaccine. She started giving informed, sourced answers to questions from the community, which now totals more than 7,000 users.

“One of the admins asked me to join the admin team — three nurses, three doctors, a pharmacist, a mom and two scientists,” she said. “The main admin got me passionate about addressing misinformation. Most of us, although we have never met, have become good friends and a support system.

“There are roughly three to six posts a day, usually moms asking vaccine questions. COVID-19 has definitely amplified the misinformation.”

Of the nearly 60 million people in South Africa, an estimated 20,000 are active on anti-vaccination Facebook pages, according to Professor Hannelie Meyer, a pharmacist and advisor to the South African Vaccine and Immunization Center.

“The pause in the COVID-19 vaccine rollout demonstrates that vaccine safety monitoring works extremely well, and in a perfect world that would build public confidence in vaccination,” Meyer told South African website News24. “However, we don’t live in a perfect world, so the pause can potentially be harmful to vaccine confidence in general, and subsequently vaccine hesitancy will rise.”

With more than 1.5 million cases of COVID-19 and more than 54,000 deaths, the pandemic has hit South Africa much harder than any country on the continent.

Downs and other anonymous experts volunteer their time, refuting viral misinformation, also known as the “infodemic.” She has watched the anti-vaccine movement that grew online over the years shift to COVID-19 claims in 2020.

In July 2020, some of the wilder conspiracies reached Downs’ doorstep when her mother’s prayer group shared a viral anti-vaccine video.

“They’re people I’ve met and are mostly in a higher-risk group,” she said. “The video said people that get mRNA [messenger ribonucleic acid] vaccines will no longer be human and can be controlled through Wi-Fi like a smart home.

“I really hate that people are put into fear like that.”

Downs dissected the video point by point in a Facebook post of more than 4,000 words with a list of links at the bottom. It was shared hundreds of times.

“I’ve been able to help a few people who have been really misled,” she said. “In the group, collectively, we have done the same.”

South Africa’s Ministry of Health recently ran a publicity campaign to counter COVID-19 myths. But misinformation leads directly to vaccine hesitancy, and it’s especially hard to fight when it comes from official sources.

In December 2020, South African Chief Justice Mogoeng prayed at a public event that “any vaccine that is of the devil … may it be destroyed by fire,” remarks he refused to recant despite sharp criticism.

In January 2021, a councilman in the east coast city of Durban made headlines with claims that it wasn’t COVID-19 making people sick but 5G cellphone towers. He also said white people in parts of his province had been vaccinated five months earlier.

“Misinformation spreads very rapidly, especially on social media,” Meyers said. That “fuels vaccine hesitancy and vaccine refusal amongst those people who do not verify information and indiscriminately share information within their own networks.

“This has the potential of having a devastating impact on public health.”

Fortunately, experts like Downs are working overtime to counter misinformation with science, expert opinions and facts.

“I’m one of many,” she said. “The more people doing it at a local level, the better the trust network.”