ADF STAFF

Border regions tend to be places of possibility and peril. They are where cultures meet. Where trade –– both legal and illegal –– thrives. Where journeys begin or end.

Because they often are far from national capitals, border communities typically receive little investment, and people living there are vulnerable to coercion by criminal groups or extremists.

“Borderlands in Africa are typically characterised by low state presence, mistrust between local communities and the state, and high levels of crime, insecurity and poverty,” the African Center for the Constructive Resolution of Disputes (ACCORD) wrote in a study of conflict management in borderlands.

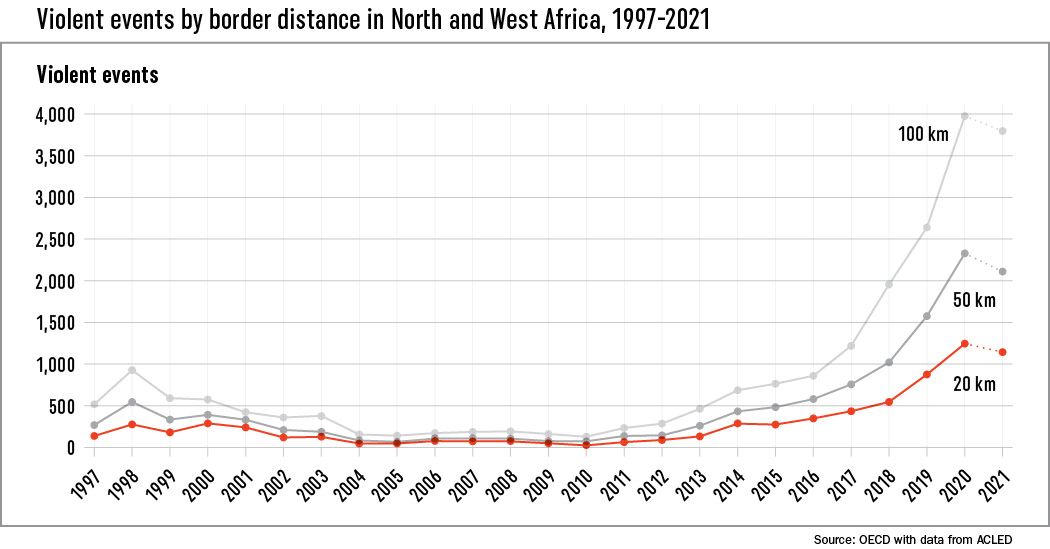

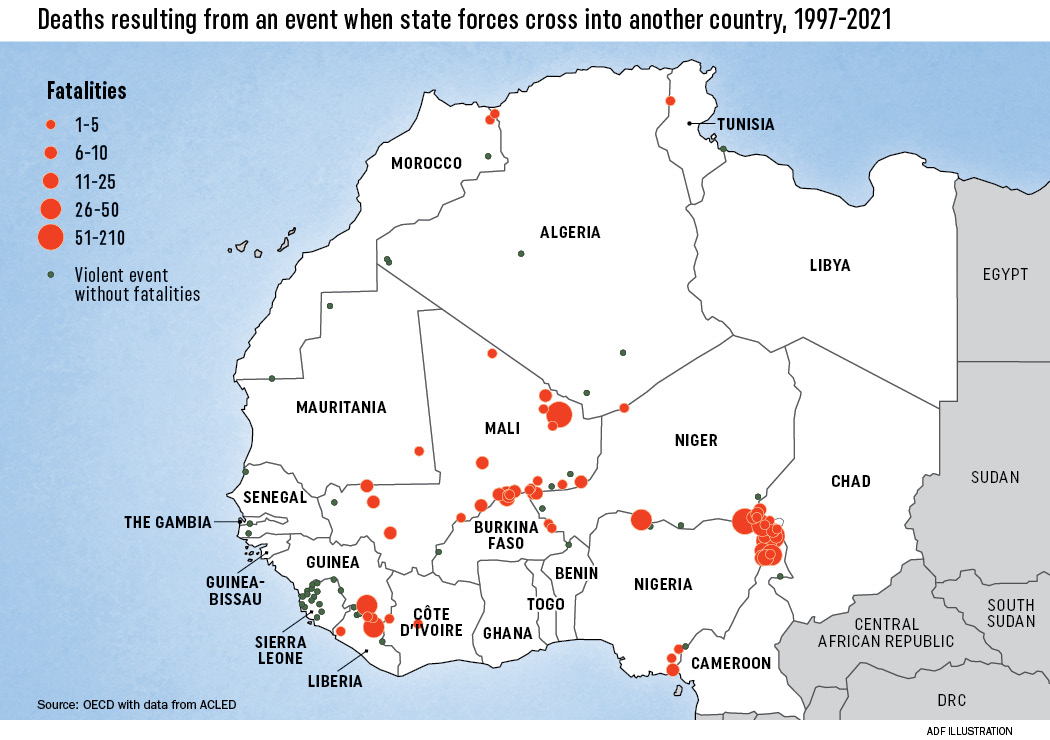

The numbers show borders are a security weak spot. In North and West Africa, 23% of all violent events occur within 20 kilometers of a border. Border violence has increased in the past decade, more than doubling between 2011 and 2021, according to an Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) report on border violence in North and West Africa. During the first six months of 2021, 60% of deaths due to violent events occurred within 100 kilometers of a border.

In fact, the OECD found that violent events generally decrease in number the farther one travels from a border.

“The concentration of violence near borders is a reminder that the circulation of money, people, and arms across the region is central to understanding the ebbs and flows of violence from state to state over time,” the OECD report said.

So, what can be done? Security professionals are examining several strategies to reclaim borders.

DEMARCATION

Often countries don’t agree on where borders actually lie. A survey by the African Union in 2015 found that only 29,000 kilometers of national borders in Africa representing 35% of the total border length were effectively demarcated.

This lack of clarity has security implications. There are more than 100 active border disputes between nations on the continent. These can lead to minor skirmishes between communities or all-out war between nations.

One country taking steps to address this problem is Ghana. The country’s boundary commission is going through the arduous process of “reaffirming” its more than 1,000-kilometer border with Togo. This involves examining legacy documents from both nations that date to the 1920s and were written in English in Ghana and French in Togo. Surveyors from both countries are replacing demarcation pillars that have been damaged by erosion or moved because they were not drilled deeply enough. The countries are increasing the frequency of pillar placement along the border to avoid confusion.

“Because of the distances of the pillars, those communities living along the boundary are not able to determine where the boundary is,” National Coordinator of the Ghana Boundary Commission Maj. Gen. Emmanuel Kotia told ADF. “They stray and farm in the territory of another country or they build houses in another country. And it’s not their fault, because they do not know.”

In order to educate the local population about the border process, the boundary commission held sensitization events, inviting groups from both sides of the border for dialogue. “We invited the local chiefs of Ghana and Togo, within the catchment areas for community sensitization, for us to educate them,” Kotia said. “We are using the media, youth groups, women groups, traditional rulers, opinion leaders, security agencies. All the people who can lend hands or help us educate.”

Ghana next will undertake the same reaffirmation process with Côte d’Ivoire and Burkina Faso. Kotia believes more countries in Africa need to create boundary commissions and pass laws to demarcate borders.

“The essence of it is to prevent insecurity, and that is one of the causes of insecurity,” he said.

A persistent complaint is that African borders are arbitrary. Drawn more than 100 years ago by colonial powers with little knowledge of the local cultures, they divide people or group them together without good reason. Pastoralists find themselves unable to move their herds freely, businesses are separated from customers and families are divided.

Dr. Wafula Okumu, executive director of Nairobi-based The Borders Institute, has worked for decades to craft effective policies relating to borders. He said security professionals need to see border communities as part of the solution to insecurity, not a problem. One thing he stressed was the need to educate border officials about the unique cultures of border regions.

“African border personnel need to change their mindset, particularly criminalizing and securitizing borderlands,” Okumu said during a webinar hosted by the Africa Center for Strategic Studies. “They need to regard border communities as stakeholders and partners in border governance.”

He emphasized the need for “integrated border management.” This strategy includes the creation of “one-stop border posts” where customs and border services of both countries work side by side. The goal is to simplify and streamline movement for all involved.

This is important because 43% of people in Africa rely on what is called “informal cross border trade” for income or goods. This trade typically involves vendors moving goods to market outside the formal customs process.

Some countries are acting to ease movement across borders. In 2023, Botswana and Namibia signed an agreement to let citizens cross the two countries’ 1,500-kilometer border without using a passport. The African Union has urged countries to adopt the African Continental Free Trade Area, which will facilitate cross-border trade, and the Free Movement of Persons Protocol, which would reduce barriers to African citizens crossing borders.

Okumu hopes there is a shift from viewing borders as barriers to viewing them as bridges to facilitate the movement of people and goods.

“Control is usually about blocking, not facilitating, easy movement,” Okumu said. “This is not free movement, but easy movement. That’s very critical.”

Border regions tend to be isolated physically and metaphorically. In its study, “How Borders Shape Conflict in North and West Africa,” the OECD found that population centers in border areas of Chad, Mali and Niger do not have paved roads connecting them to a national capital. They also found a lack of medical, educational and social services in these regions.

“Insurgencies emerge when peripheral communities feel marginalized and the state is unable to maintain national cohesion,” the OECD reported.

In his three years as head of the Ghana Boundary Commission, Kotia has witnessed a similar dynamic.

“Most of the border communities are in remote areas, forgotten by states,” he said. “Most of them are deprived. So, violent extremist groups will look at such areas where there are deprived communities as targets to recruit them in any part of Africa. They can be targets.”

He pointed to two projects in Ghana that are trying to address this problem. One is the construction of a health center in the Volta Region funded by the Economic Community of West African States. The other is an effort to get road infrastructure to an informal mining community in a town called Dollar Power near the border with Côte d’Ivoire. There, 10,000 people work in unregulated artisanal mines in an area only accessible by motorbike.

The 24-kilometer road project, which is being constructed by the Ghana Armed Forces 48 Engineering Regiment, will help authorities access the isolated region. By connecting this region to the outside world, Ghanaian authorities hope to undercut traffickers and extremists.

“The issue of deprived border communities is very fundamental,” Kotia said. “We need for governments to pay attention to deprived border communities because they can be easy targets for recruitment as far as violent extremist movements are concerned. They can also use those spaces as safe havens to launch attacks.”