Early Warning Systems Help with Alerts, Defections

These days, the Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA) can scarcely make a move without it being documented and passed on. Consider these incidents:

- January 10, 2014 – A 38-year-old LRA soldier who spent 20 years in captivity defects in Djemah in the Central African Republic (CAR) after walking six days in the bush. He had listened to radio broadcasts urging LRA members to give up their arms.

- February 9, 2014 – After hearing defection messages over helicopter speakers, four Ugandan LRA soldiers defect to security forces. They had been in captivity for 12 years.

- March 1, 2014 – Terrified villagers report seeing suspected LRA forces 5 kilometers from Obo in the CAR.

Even the most mundane incident, such as the March 1 sighting, is noted and passed on via a system of radio stations throughout the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) and elsewhere. The incidents also are documented by Invisible Children, an organization started by three Americans.

The radio network dates to 2007, when a Catholic priest helped set up the LRA early warning system with a network of radio transmitters originally used by missionaries in the DRC. The network has grown dramatically since then and is now used to alert villagers, United Nations workers and nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) of LRA sightings.

The radio network dates to 2007, when a Catholic priest helped set up the LRA early warning system with a network of radio transmitters originally used by missionaries in the DRC. The network has grown dramatically since then and is now used to alert villagers, United Nations workers and nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) of LRA sightings.

The LRA has existed for more than two decades. Led by Ugandan Joseph Kony, it had its roots in opposing the Ugandan government but now has no coherent political agenda. It has proved to be mobile and difficult to eradicate, moving through areas in the northern DRC, the CAR and South Sudan.

Officials estimate that since 2008, the LRA has killed more than 2,600 civilians and abducted more than 4,800 others. In 2013, LRA soldiers killed 75 people and abducted 459. In February 2014, LRA soldiers killed only one person and abducted 76.

Kony’s soldiers sleep in jungle camps, under trees and brush that hide them from drone monitoring and satellite surveillance. They do not use two-way radios because their signals can be tracked, and they don’t attack large villages that might be able to quickly summon help.

LRA leaders are experts in exploiting the region’s rugged terrain. In December 2008, the DRC, Sudan and Uganda launched Operation Lightning Thunder, a military offensive against the LRA in the northeast DRC. The operation weakened the LRA by cutting off food and supplies and destroying some camps. But the group did not disappear; instead, its members scattered across the rough country and later responded with a series of bloody attacks on civilians in Sudan and the DRC.

Such attacks are where early warning systems can be most effective. The growing network of high-frequency shortwave radios now connects rural villages in the DRC and parts of the CAR. Starting with the missionaries’ network, other transmitters have been added to fill the gaps. All the radio transmitters are increasingly working with the Invisible Children’s Early Warning Radio Network.

Invisible Children, a nonprofit NGO, was founded in 2004 to support and protect Kony’s victims. In March 2012, the organization began an Internet video campaign called Kony 2012 that was viewed more than 40 million times within three days. The video is largely responsible for the worldwide attention focused on Kony.

Expanding Networks

The early warning system in the DRC is only part of a larger picture on the African continent. In 1985, there were fewer than 10 independent radio stations in all of Africa, according to the World Association of Community Broadcasters. By 2005, the DRC alone boasted more than 200 radio stations.

Working with other groups, including Human Rights Watch, the Invisible Children Early Warning Radio Network has capitalized on this radio infrastructure. Two times a day, villages in the network check in and report on recent events and sightings. The reports, in turn, are routed to network hubs. The information alerts villages of threats, can help mobilize military forces in the region and solicit help from humanitarian workers.

Defections Encouraged

A key component of the radio network is a defection messaging initiative, in which local radio stations broadcast calls for LRA rebels to come home to their families. The messages often target specific rebels by name, with family members included in the broadcasts. The defection campaign includes helicopters playing messages over speakers and airplanes dropping leaflets about amnesty and forgiveness. Invisible Children reports that about 320 people escaped from the LRA in 2013, and 16 soldiers defected. Nearly 2,300 people have left or escaped from the LRA since December 2008.

Getting LRA soldiers to defect and surrender has been a key component for years in the war against Kony. Military writer David Axe said the tactics first were used in the northeastern DRC town of Dungu in 2009. In 2008, the LRA attacked the town, forcing its 20,000 residents to temporarily flee. Since then, the town has been the base of operations for many NGOs and other organizations trying to help LRA victims, as well as persuade LRA soldiers to desert.

The network has had a tangible effect on Kony and his troops. With the DRC better informed, Kony has been forced to move the bulk of his troops to the relatively lawless CAR, which it first invaded in 2008. He left behind a skeleton crew of soldiers to operate along the eastern DRC. It was these soldiers, estimated to number no more than a few dozen, who were the first targets of the Dungu radio broadcasts. It was believed that, with Kony absent, the soldiers would feel they could defect without facing reprisals.

The radio broadcasts are aimed at three audiences: kidnap victims, hardened LRA soldiers and DRC residents. The kidnap victims are urged to escape. The LRA soldiers are told that they can surrender without fear of punishment. DRC citizens are given current information on LRA movements.

Because of the atrocities, many rural DRC residents will quickly kill anyone they believe to have LRA ties. Villagers have been known to kill LRA soldiers who were attempting to desert. Now, radio broadcasts urge listeners to allow the LRA soldiers to surrender unharmed. To that end, the United Nations established “surrender posts” where rebels could go to turn themselves in along the border with South Sudan. More recently, the United States has established posts of its own.

As 2014 began, villages throughout the region were stepping up their use of radio stations to transmit messages to individual members of the LRA, urging them to desert. One such broadcaster is John B. “Lacambel” Oryema, who hosts a radio program called Dwog Paco, which means “Come Back Home” in Acholi. He broadcasts from a state-owned station in northern Uganda.

Oryema has been broadcasting his messages to the LRA since 2001. He solicits messages from community members to target specific LRA members.

“I try to make it in such a way that they would be happy to hear their names, happy to hear that their parents are here surviving, their parents are longing to see them,” he said.

The History of the Lord’s Resistance Army

ADF STAFF

- 1986

Yoweri Museveni overthrows President Milton Obote and becomes president of Uganda, a position he holds to this day. - 1987

Alice Lakwena, a self-proclaimed Acholi priestess, forms a rebel group, the Holy Spirit Mobile Forces. Another rebel group, the Uganda People’s Democratic Army, forms with Joseph Kony as a “spiritual advisor.” - 1988

The Holy Spirit forces are defeated, and Lakwena flees to Kenya. Kony recruits the remaining people in her movement and forms the Uganda People’s Democratic Christian Army, which becomes the Lord’s Resistance Army in 1993. - 1991

Kony launches a military campaign. From April to August, his rebels seal off the northern districts of Apac, Lira, Gulu and Kitgum from the rest of Uganda. Kony and his troops begin murdering, maiming and mutilating civilians. They also begin destroying villages and taking children prisoner to train them as soldiers. - 1993-1994

Uganda begins peace talks with the LRA. In February 1994, the LRA rejects President Museveni’s demand to surrender and launches armed attacks against Ugandan Army units and civilians. LRA soldiers plant land mines on main roads and footpaths in the northern part of the country. - 1995

A new Ugandan constitution legalizes political parties but maintains the ban on political activity. The LRA kills more than 200 people and carries out the first large-scale kidnapping of children. At year’s end, the LRA is forced out of its base in southern Sudan. - 1996

The LRA commits more mass atrocities. Ugandans flee their homes in fear of the LRA and are moved to “protected villages” in Gulu. Conditions at these villages create a crisis of their own. - 1997

In January, the LRA kills 400 people in Lamwo County and Kitgum district, and thousands more flee their homes. The government resolves to fight the LRA, ruling out peace talks. - 1999

Parliament passes an amnesty bill offering immunity to rebels who surrender. The LRA attacks Gulu at the end of the year, ending any hope for peace. - 2001

The United States puts the LRA on its list of terrorist organizations. - 2002

Sudan and Uganda sign an agreement aimed at containing the LRA. Uganda launches Operation Iron Fist, aimed at wiping out Kony’s forces. The LRA responds by attacking refugee camps in northern Uganda and southern Sudan, killing hundreds of people. The Ugandan Army evacuates more than 400,000 people threatened by the LRA. - 2004

In February 2004, an LRA unit attacks the Barlonyo refugee camp in Uganda, killing more than 300 people, most of them women and children. - 2005

The LRA moves its base of operations to the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC). It intensifies attacks on civilians in refugee camps. - 2008

Uganda suspends the Juba Peace Talks indefinitely after Kony refuses to sign a binding peace agreement. At the end of the year, Ugandan, Congolese and southern Sudan Soldiers launch Operation Lightning Thunder against the LRA in the northeast DRC. The LRA responds by killing hundreds of civilians in the region. - 2009

The Ugandan Army withdraws from the DRC after chasing LRA rebels in a three-month operation. - 2011

The U.S. sends 100 troops to help Uganda fight the LRA. - 2012

Uganda announces it will lead 5,000 African Union forces to fight the LRA in the DRC and Central African Republic. - 2014

The United States discloses that its mission to help track down Kony could extend well into 2015.

‘Regional Cooperationis Essential’

ADF STAFF

Africa Defense Forum spoke with Sean Poole (pictured), Invisible Children’s program manager of Counter-LRA Initiatives, in March 2014. He’s directly involved with the radio network that tracks LRA movement. Here are excerpts from the interview:

![[INVISIBLE CHILDREN]](https://adf-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/SeanPoole_Color-863x1024.jpg)

What’s your job with Invisible Children?

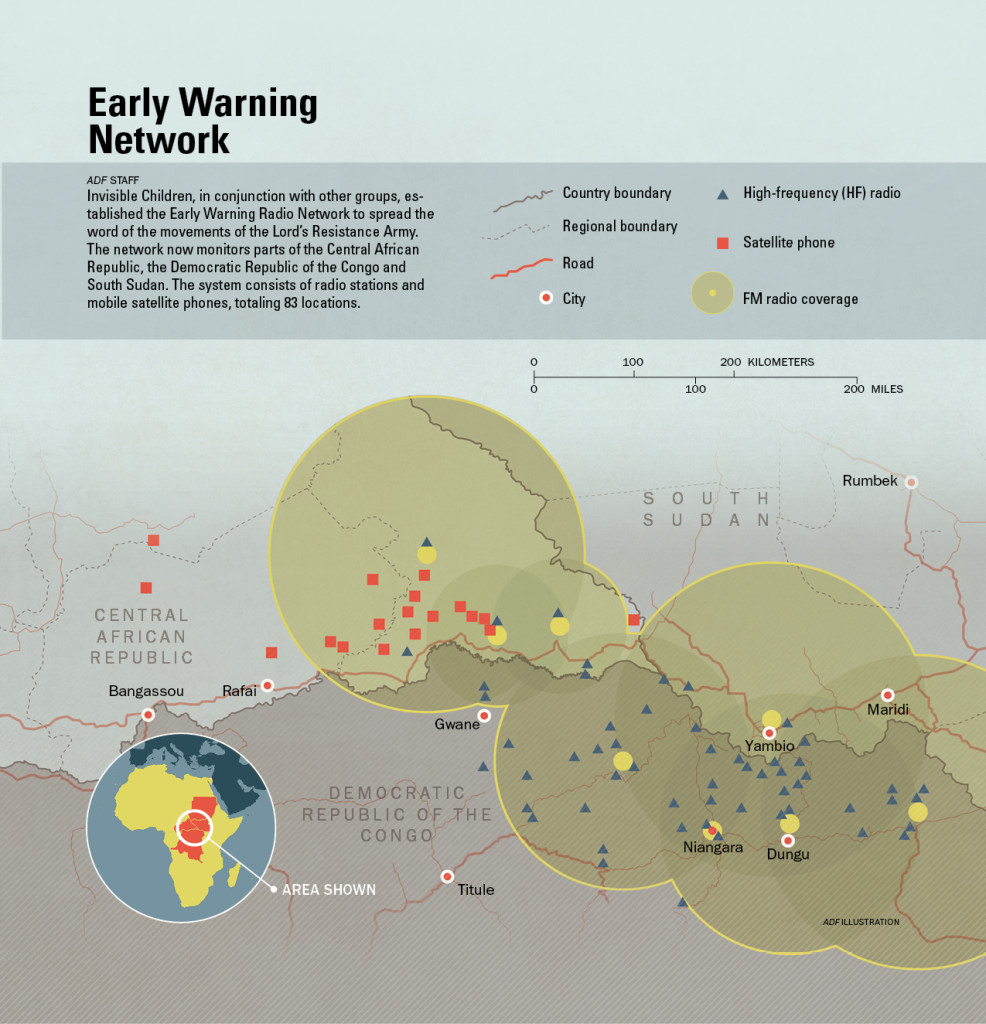

I’m involved in information collection on the LRA in Central Africa. Our information collection network includes 83 locations in the DRC (Democratic Republic of the Congo) and the CAR (Central African Republic).

We built our network from what was available when we started. About 75 percent of our locations are high-frequency stations. Each station costs about $18,000 to $20,000 over the course of the three years it takes to get it installed and running. The other 25 percent are Thuraya mobile satellite phones.

Do you have any presence in Uganda, where the LRA started? When did you expand the network into the CAR?

The network is not in Uganda. The network started activities in the CAR in 2011.

Do listeners avoid contact with the LRA based on the radio broadcasts?

That function occurs; it’s just not something we report on our website. What we produce publicly is information on attacks, displacements and lootings.

From the sighting reports on your website, it seems that the LRA is a bit less violent than it has been in the past.

There is a trend of less violence among the LRA. These days, they are taking people hostage and using them as porters, releasing them after three days. It’s because of the overall trend of the LRA in a weakened state. The LRA is more interested in looking after the people they already have than in trying to look after new hostages.

Boko Haram, Nigeria’s extremist group, destroys radio stations and kills the people staffing them. Has that been a problem with the LRA?

We haven’t had problems with attacks on radio stations like other countries have had with Boko Haram. We do a good job of concealing our stations and protecting them. Our stations are so low profile, I think the LRA may not even be aware of the network.

Did you learn any lessons from conflicts in other parts of the world?

We learned a lot from the conflict in Colombia involving FARC (the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia). Many of the members of FARC would want to go home if they could. The government had an effective defection campaign.

What can other countries learn from your network?

What we’re actually gathering is open-source information that can be applied to a variety of problems. It’s a good problem-solving approach.

We also learned that once the Congolese got involved with tracking the LRA, we saw much more cross-border collaboration. The kind of regional cooperation we have now is something that should be applied elsewhere, and not just with the military. A lot of these affected communities straddle the border of the DRC and the CAR, and regional cooperation is essential.

What’s the future of the LRA?

They have a propensity for beating the odds and have found a way to survive in spite of seemingly insurmountable odds. They’re like a virus; they can always grow back. I think Joseph Kony will be eventually killed or captured. If that happens, it would be the beginning of the end of the LRA.