ADF STAFF

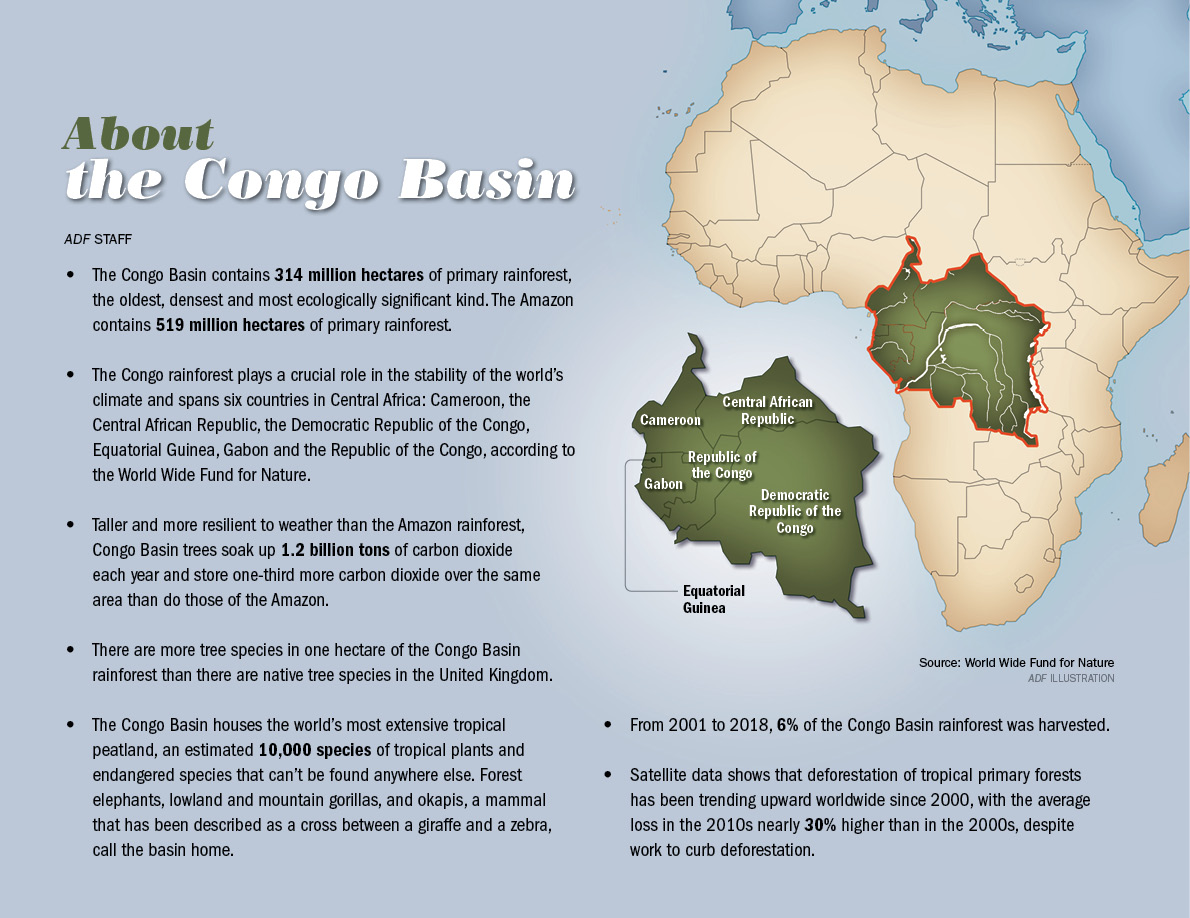

The Congo Basin rainforest is huge, second only to the Amazon. It sprawls across six nations, but it is shrinking.

The basin is the home to countless species of plants and animals. It also is a key to the health of not just Africa, but the entire world, because it soaks up carbon dioxide from the atmosphere.

Deforestation in the Congo Basin is higher than in recent years. Nearly all primary forest lost in the basin in the past 15 years is in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC). Still, compared to the rainforests in Asia and South America, the Congo Basin remains relatively strong, according to the environmental website inhabitate.com.

The greatest threat to the Congo Basin is poverty. The clearing of trees in the basin to produce charcoal and grow cash crops remains one of the few opportunities for the rural poor to make a living. But such farming and clearing is wildly inefficient. Much of the region has no electricity, and without it, food cannot be stored or processed, businesses cannot be started, and key sectors such as health and education cannot be developed.

Illegal logging also plagues the region. The DRC is well aware of the problem and has established a forest code for safe logging. But in the DRC, as in much of Sub-Saharan Africa, the code is not enforced. Officials are bribed to look the other way as illegal loggers cut down trees, especially rosewood trees, and ship them to China to be used in fine, handmade furniture.

Chinese merchants have harvested the endangered trees in virtually every African country that has them. It could be worse. Many African forests have been spared illegal logging because the infrastructure is so poor that getting the timber out is too expensive. This is not the case in vast parts of the DRC, because the Congo River is such a good means of transportation.

Critical to World Health

Sometimes known as the world’s “second lung,” the Congo Basin is critical to a healthy environment.

“Being a major storehouse of biodiversity, it provides huge services to all of humanity,” Simon Lewis, a geographer at University College London, told the BBC. He has been doing field work in the Congo Basin since 2002.

“The intact rainforest in the Congo Basin, which until now has suffered less deforestation and shown more climate resilience than the Amazon, has played a very important role,” he said.

Lewis has found in his research that increasingly common droughts are reducing the ability of the rainforest to absorb carbon dioxide. His study looked at 135,625 trees across 244 African plots in 11 countries. He found that trees in the Congo Basin, whose growth had been stifled by extreme weather, started to lose their ability to absorb carbon dioxide as early as 2010.

As the Congo Basin’s trees become unable to soak up carbon dioxide, the number of trees in the rainforest also is diminishing. Industries such as logging, palm oil plantations and mining are contributing to deforestation, Lewis concluded.

2020 brought great hope of collective action to save tropical forests. Global leaders planned to gather and assess the progress in the past 10 years and set the climate and biodiversity agendas for the next decade.

Writing for Mongabay, a nonprofit conservation and environmental science news platform, founder Rhett A. Butler said there was good reason for optimism. The world’s heat and droughts were becoming so apparent that they finally were starting to provoke a response from the public and private sector, he said. Technological advances were improving forest monitoring to the extent that ignorance was no longer an excuse for inaction. Interest in forest restoration was reaching new heights.

Writing for Mongabay, a nonprofit conservation and environmental science news platform, founder Rhett A. Butler said there was good reason for optimism. The world’s heat and droughts were becoming so apparent that they finally were starting to provoke a response from the public and private sector, he said. Technological advances were improving forest monitoring to the extent that ignorance was no longer an excuse for inaction. Interest in forest restoration was reaching new heights.

But, he said, COVID-19 changed everything. As governments pumped money to prop up financial systems, it resulted in high demand for commodities such as hardwood.

“Some governments put forth bailouts, economic stimulus packages, and other incentives for forest-destroying industries,” Butler wrote. “Millions of people left cities for the countryside, reversing a long-term trend of migration to urban areas.”

The DRC accounts for about 60% of the Congo Basin’s primary forest cover and nearly 80% of its loss. Butler said the country can be viewed as a bellwether for the entire region.

In January 2020, the DRC granted nine forest concessions covering more than 2 million hectares to two Chinese companies, which environmentalists said violated a national moratorium on such new contracts.

In January 2020, the DRC granted nine forest concessions covering more than 2 million hectares to two Chinese companies, which environmentalists said violated a national moratorium on such new contracts.

It’s not just the DRC. Gabon historically has had a low deforestation rate. But the Forest Stewardship Council is investigating whether Singapore-based agribusiness giant Olam has deforested more than 25,000 hectares in Gabon to develop oil palm plantations contrary to sustainability rules it had agreed to. The company also stands accused of deforestation to make room for rubber plantations.

Daunting Task

There is a consensus about certain basic facts related to deforestation and what can be done to reverse it:

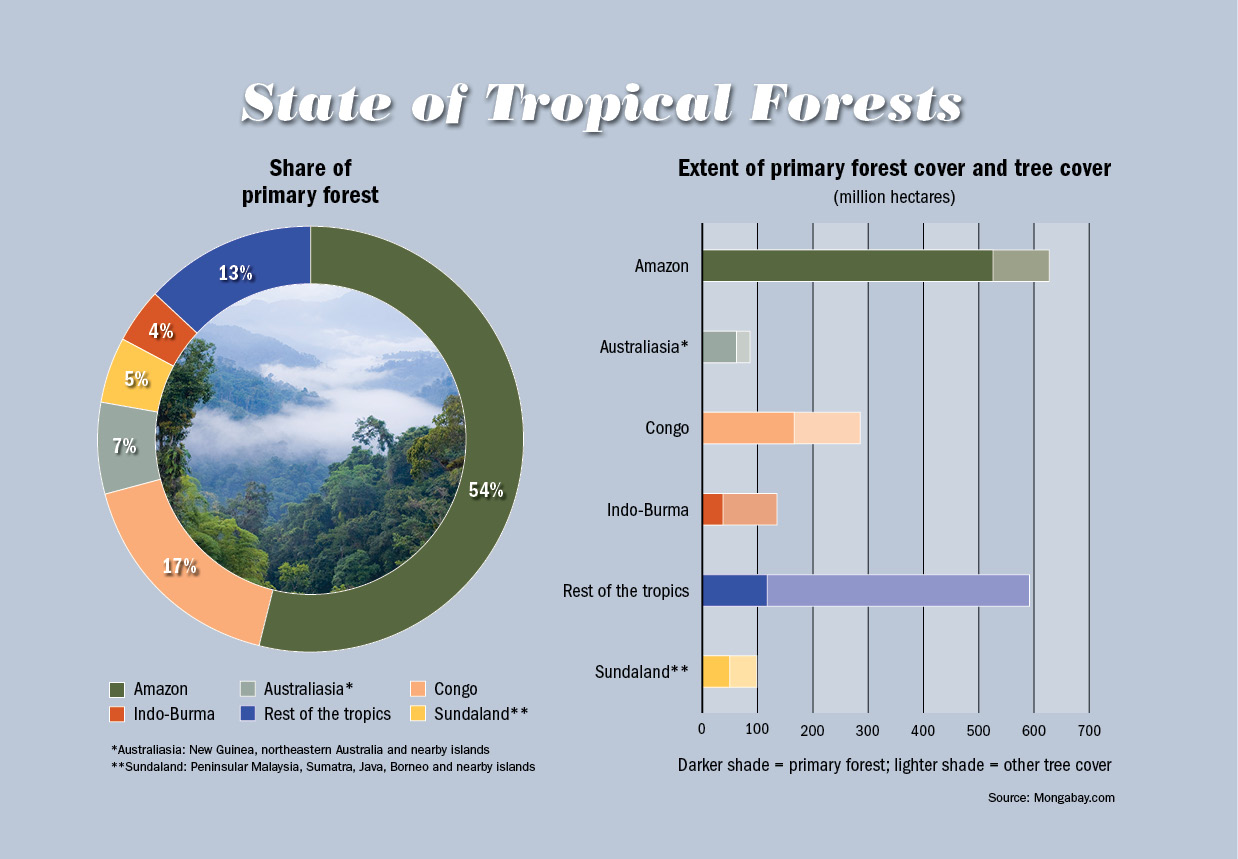

It’s not an African problem; it’s a world problem. The Amazon makes up more than half the world’s rainforests, and the Congo Basin totals about 17%. The rest of the world’s rainforests are scattered around the tropics, particularly in Asia. It won’t be enough to save just the Congo Basin; other countries with rainforests will have to do their parts.

Farming practices have to be modernized. Lacking access to machinery and fertilizer, subsistence farmers have to make use of crop rotation, better irrigation techniques, and find better sources for seeds. Through smart phones, they can get individual planting tips from regional experts. They will need to find sustainable, affordable ways to control weeds and pests.

Start enforcing rules and laws prohibiting illegal logging. Virtually every part of Sub-Saharan Africa plagued by the illegal harvesting of rosewood already has laws to prevent it. But as long as loggers, usually backed by Chinese companies, continue to bribe officials, rampant harvesting will continue.

Start aggressive tree-replanting programs in the Congo Basin. Replanting requires incentives. Researchers from the World Agroforestry center have surveyed farmers in West Africa and found that they prefer planting indigenous fruit trees. The Global Forest Atlas notes that “An important component of agroforestry in the Congo Basin is selecting valuable fruit trees that can produce high yields. Much of this selection is done through a process known as participatory domestication, where researchers work with communities to select varieties and adapt them for local use.”