Dr. Mark Duerksen is a research associate at the Africa Center for Strategic Studies. His research focuses on Nigeria’s security landscapes and Africa’s unparalleled urbanization, along with the security challenges and opportunities that cities present. His projects at the center include tracking security-related news and creating analytic infographics. Africa Defense Forum (ADF) interviewed Duerksen via email. His remarks have been edited to fit this format.

ADF: Are Nigeria’s mercenary groups actually working? It seems that many of them become as bad as the organizations they are set up to combat. For instance, a federal judge in Nigeria said the Bakassi Boys are “nothing more than outlaws.”

Duerksen: It’s a complicated question, and it’s not always clear whether Nigeria’s regional and local nonstate security outfits are working, and it may be too early to tell in some cases. I think it’s important to distinguish between:

- Private security organizations that are usually contracted by private interests.

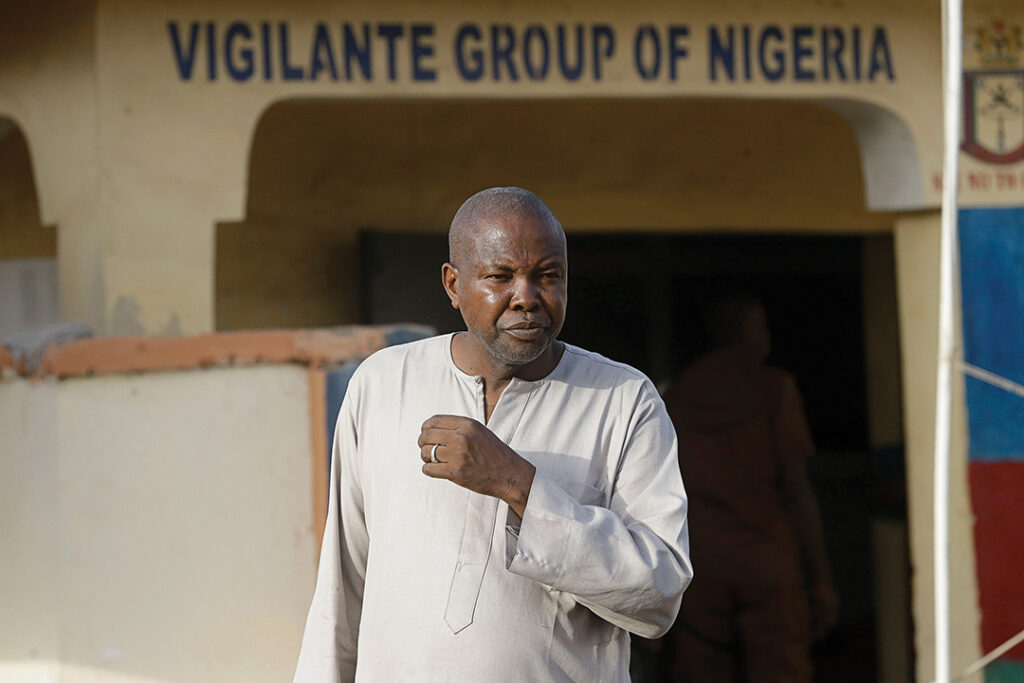

- Local militias and vigilante groups that are set up to defend local property and communities, and sometimes are condoned, equipped and trained by local governments.

- Regional security outfits that are set up or officially sanctioned by state governments, even if their constitutionality is disputed.

All of these forces sometimes overlap geographically and operate in Nigeria in addition to the country’s myriad military forces, numerous divisions of federal police, as well as other security forces such as the State Security Service. So, there’s really a “soup” of security responses in Nigeria of all these different groups ostensibly trying to make the country safer from the diversity of armed groups operating in the country.

In the case of turning to vigilante groups or new regional forces to fill the security vacuum, these groups often follow a similar pattern of eventually engaging in the kinds of criminal behavior and abuses that they were tasked with preventing. This is the case with the self-defense militias in North West — they were initially established by local farmers to protect their interests against well-armed herder-aligned militias, but over time they have engaged in torture, atrocities and have even become feeders for the notorious criminal gangs that operate in the region.

Outcomes like this, which are also seen in the case of the Bakassi Boys, are the result of these forces having less oversight and receiving even less training than official security forces.

ADF: Are there some exceptions to this?

Duerksen: Yes, there are absolutely communities that have benefited from establishing local outfits that patrol and keep a lookout, but this is often dependent on the dedication and oversight of individual local leaders rather than institutional checks and accountability. So it can be difficult to replicate any of these successes to make a significant dent in Nigeria’s systemic insecurity.

Ultimately, these “alternative” security solutions are unlikely to deliver sustainable results unless they can be integrated into official institutions that will monitor, train and hold them accountable. In the meantime, documented violent events by armed groups in Nigeria have increased significantly over the past five years, from under 700 events per year to over 2,000 per year. Every year a significant number of events involving violence against civilians are attributed to Nigeria’s security forces and to militias that were originally set up to increase security locally.

ADF: Despite all the publicity at their startups, the mercenary groups Amotekun and Shege-Ka-Fasa do not appear to be accomplishing much of anything.

Duerksen: It is unclear what either of these groups is accomplishing beyond generating controversies over their legality. Meanwhile, the rash of kidnappings for ransom in the north and the security sector violence against civilians in the South West continues. Additionally, regionalizing security may create unintended problems if these forces operate with ethnic bias or under a banner of ethnic nationalism. Eventually, if these regional forces are not professionalized, they may aggravate regional divisions, which have long plagued Nigeria. The last thing Nigeria needs is a buildup of regionally loyal and ethnically organized security forces, especially when they’re connected to separatist groups like the Eastern Security Network, which was recently established by the leaders of the Indigenous People of Biafra’s militant movement.

ADF: It seems likely that the only long-term solution to the country’s security problems will be a commitment to hiring and training more police and, possibly, more Soldiers, and abolishing the practice of mercenaries. Is that a flawed theory?

Duerksen: The problem is that more often than not, setting up new forces or taking matters into one’s own hands via vigilante groups or newly sanctioned security outfits is the path taken in Nigeria instead of politicians and civil servants engaging in the challenging and long-term work of security sector reform, professionalization and trust building. Sensible reforms have been proposed by expert panels, but these haven’t ever been fully implemented, and, over the years, the police units in need of reform have essentially been rebranded under new names and reconstituted without addressing their underlying issues. There are some proposals and optimism that more effective units could be established through community policing initiatives. So, there is room for innovation and new ideas so long as they are created to tackle the problems identified by review processes and their results are assessed over time. This could also be done through the creation of public safety forces, which would help Nigeria look toward more comprehensive and integrated security solutions.

In short, Nigeria’s security architecture can be overly complicated and nebulous and often lacks the transparency and accountability needed for effective reform — something that needs to be addressed in the process of developing a multidimensional national security strategy. A serious reform and training effort of the country’s military and police with a focus on integrated security responses (involving government services, social development and justice initiatives) is Nigeria’s best bet for tackling the diversity of security threats the country faces.