Success for Soldiers Must Include Education in Addition to Basic Military Training

An African Soldier deployed to the United Nations mission in the Central African Republic will have to know far more than the boundaries of his patrol area or how to clean his gun.

If, say, he is from South Africa or Ghana, he will face an immediate language barrier. Most people in the country speak French or Sangho, an African-based Creole language. Others speak a variety of disparate tribal dialects.

The peacekeeper will encounter more than seven prominent ethnic groups, three major religions and multiple indigenous belief systems, as well as local and regional cultures too numerous to mention. He will not know the local leaders. Regarding culture, it’s unlikely that he will know anything at all.

This puts him and fellow peacekeepers at an immediate disadvantage. He will arrive in the country with hard skills that are tested and reliable. Still, in some ways, he is likely to be considerably unprepared for the job before him.

Pre-deployment training for peacekeepers typically involves four to six weeks of administrative or combat-related tasks and skills, Nana Odoi wrote in a paper for the Kofi Annan International Peacekeeping Training Centre in Ghana. However, for most African nations, “the cultural component within this pre-deployment training tends to be neglected, as most of the four weeks are spent on general administration and combat tasks and thus the training of ‘hard skills,’ ” Odoi wrote. “Thus there seems to be a lack of understanding within the military that cultural competencies, so-called ‘soft skills’ actually support the functional implementation of ‘hard skills.’ ”

WHAT IS THE HUMAN TERRAIN?

Terrain is an everyday concern for Soldiers in any deployment, be it domestic or foreign, in conflict areas or during peacetime. Trucks and tanks need to navigate roads effectively. Soldiers must know what to expect from the climate and where best to set up bases and camps. All of this is the stuff of basic military training and operations.

But there’s a second type of terrain that can’t be seen on any map or satellite image. Dr. Lindy Heinecken, professor of sociology at Stellenbosch University in South Africa, and others call it the “human terrain.” This encompasses legal, political, social, gender and economic matters. Heinecken told a Land Forces Africa conference in 2012 that understanding these matters helps Soldiers see things from a local perspective. Only then can they understand the “culture, traditions, practices [and] power structures of the host country they are trying to assist and not to be seen as an intervening force, pushing an agenda down on the population.”

Warfare is “unconventional, irregular and population-centric,” Heinecken said. “So this implies that the personnel have to operate in largely civilian contexts, firstly, and then secondly that there is a greater need to understand the indigenous power structures and the socio-economic considerations that affect these missions.”

The difference in the two terrains underscores the differences between training and education. “Training is the how to do it,” Heinecken told ADF. “Military training imparts particular skills that are directly relevant to the conduct of military operations, such as weapon handling, strategies of warfare and what is required.”

“Education is really the why rather than the how,” she said. It seeks to instill critical thinking and problem-solving skills. The challenge arises when trying to integrate it into training.

THE TOPOGRAPHY OF THE TERRAIN

The human terrain includes several rocky issues. Despite their prominence in conflicts and peacekeeping missions all over the continent, efforts to educate Soldiers in how to deal with them are not always common. Among the major categories are:

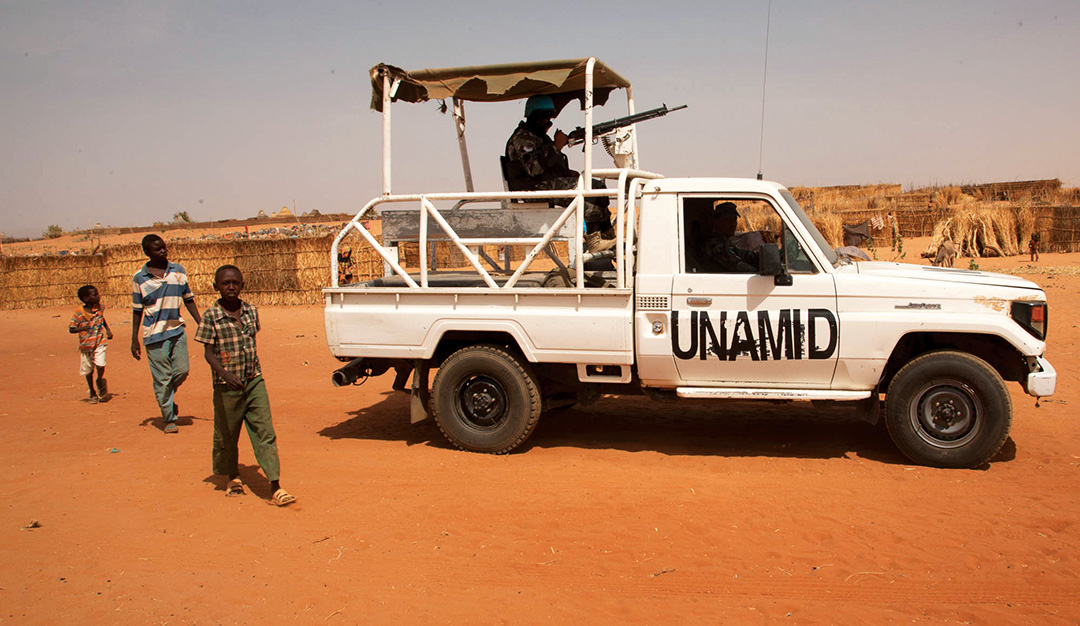

Women: One example Heinecken used from the African Union/United Nations Hybrid Operation in Darfur (UNAMID) is the gender context of military operations, particularly how conflict affects men and women differently.

“In my conversations with the peacekeepers, all of them said to me that they only ever had pure military training,” Heinecken said. “They have not been given the training to understand why it is that women are affected so severely by these wars. They don’t even really understand how rape as a weapon of war can be used so effectively. … They don’t understand how patriarchy works. … They also don’t understand, for example, how these type of wars, by targeting women in the wars, can destroy the entire social fabric of society and how effective this is in destroying communities.”

The U.N. has made a concerted effort to increase the representation of women in peacekeeping operations. The number of female uniformed Soldiers is 3 percent, the number of female police personnel is 10 percent, and the number of civilians serving in missions who are women is now nearly 30 percent, according to 2012 figures published by United Nations University. In 2014, Maj. Gen. Kristin Lund of Norway became the first woman to serve as force commander in a U.N. peacekeeping operation when she took charge of the Peacekeeping Force in Cyprus.

Race and religion: In UNAMID, a lack of understanding about why people in Darfur are fighting has led to blunders. Such mistakes can confound tactical operations. Heinecken tells of a time when peacekeepers sent a black Muslim to a meeting with representatives of the Janjaweed, a nomadic Arab militia that is at odds with farmers in Darfur. Although the Darfuri conflict often is oversimplified into being merely a dispute between blacks and Arabs, it does hinge largely on clashes between darker-skinned farmers and lighter-skinned Arab herders. She said it would have made more sense to send an Arab Muslim, or even a Christian, because the conflict essentially is rooted in ethnic, as opposed to religious, differences. On the surface, however, commanders mistakenly thought sending a Muslim to hold discussions with other Muslims made the most sense.

These problems are not unique to peacekeeping missions. They can arise any time Soldiers are deployed to a place where they must interact with civilian populations and other groups, such as nongovernmental organizations.

History and culture: For troops deployed outside their home countries, knowledge and proficiency with regional history and local culture is important. Understanding the roots of a conflict is vital to resolving it. For example, U.N. peacekeepers operating in Mali would be well-served to know that the nation’s Tuareg population has long sought independence from the government in Bamako. In Sudan, a peacekeeper must know how the country was founded and the history of the fraught relationship between the central government in Khartoum and outlying areas.

The U.N. Infantry Battalion Manual recommends that “all peacekeeping personnel have a thorough understanding of the history and prevailing customs and culture in the mission area, as well as the capacity to assess the evolving interests and motivation of the parties.”

INTEGRATING MILITARY EDUCATION, TRAINING

The list of courses for one African nation’s recruit training program highlights the focus of most basic military instruction: Drill and Duties Advance Course, Drill and Duties Basic, Skill at Arms advance, Skill at Arms basic, and Recruits Basic Military Training.

That’s not to say that there are no educational opportunities for African military professionals that address the issues of the human terrain. The Kenya Military Academy offers “excellent courses,” Heinecken said, and the International Peace Support Training Centre says it aims “to provide peace operations training and advice to all Kenya Armed Forces, Police and civilian establishments.” The South African Military Academy also is revamping its courses. Often, however, these services are most available to an elite corps of Soldiers. How much of the knowledge filters down to the rank and file is unclear.

Dr. Abel Esterhuyse, associate professor of strategy at the South African Military Academy, told ADF that when it comes to education, it’s best to do as much as possible as early as possible. “If you don’t open the minds of the military before they enter their careers, there’s no foundation to work with in the provision of this education,” Esterhuyse said. “And it’s very difficult to educate a trained mind. … You need to open somebody’s mind before you can train him. If you train him, if you box his mind before you’ve educated him, it is very, very difficult to provide this education, this contextual education, that you are talking about.”

What African nations are missing, Esterhuyse said, is a “feedback loop” through which senior, experienced officers can come back from deployments and share knowledge, experiences and lessons learned with younger, less-experienced Soldiers.

“They are educated, they served in high command and then they disappear,” he said. “We don’t bring officers back into the system to teach again. So we don’t have a full-circle educational process; it’s a one-dimensional way. We educate them, and we phase them out. And I think that’s a critical problem in African militaries.”

Such a process would fill in the gaps left by conventional military training. Heinecken said militaries operate as hierarchies: Orders are given, then followed. The culture doesn’t promote lateral decision-making, critical thinking, problem-solving or analysis. “You need more of that to be developed at the lower levels so that when they see a situation, they can understand it, make sense, draw lessons learned, draw sort of intelligence and make intelligent and informed decisions.”

1 Comment

Human Terrain is a critical subject in this modern warfare