ADF STAFF | Photos by REUTERS

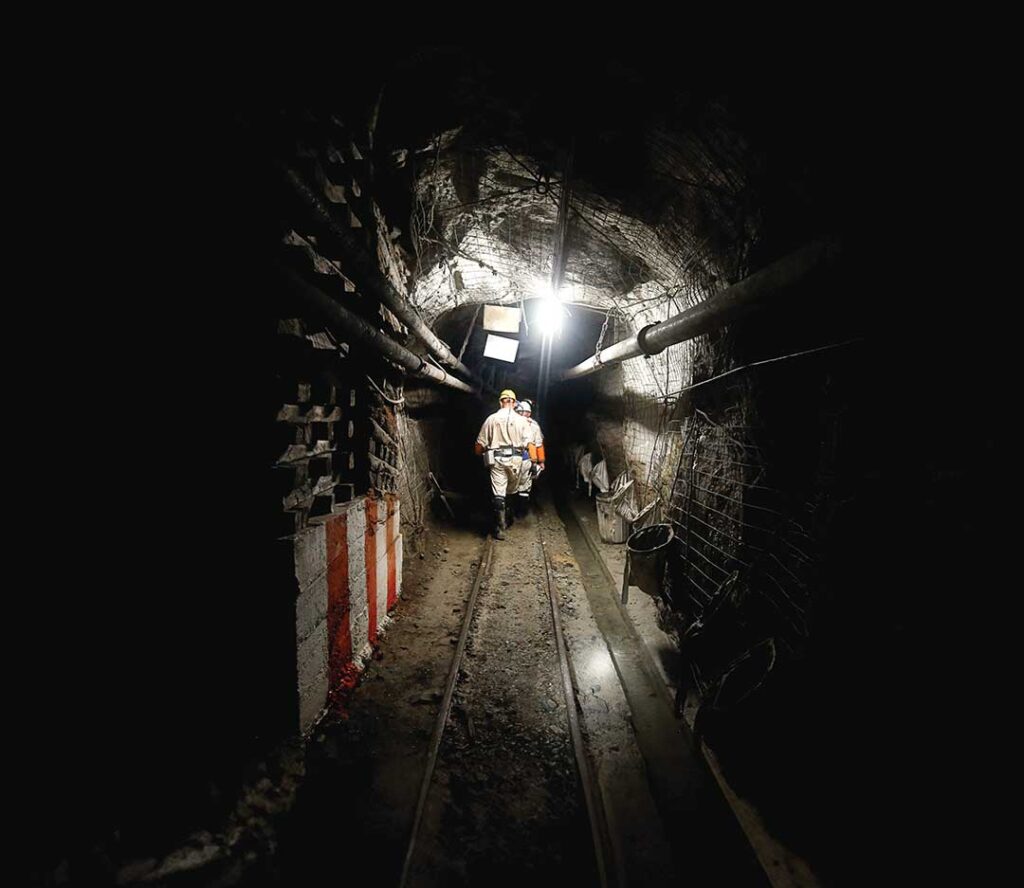

Over the past decade, Sudan has become the third-largest producer of gold in Africa. The industry gained momentum after the secession of South Sudan in 2011 when the country turned to mining to compensate for the two-thirds of the oil wells it lost in the split.

But this natural wealth has not benefited the population. Instead of the gold being mined by the private sector and taxed accordingly, the mining is in the hands of the military.

Sudan’s military is deeply involved in the country’s economy, from gold mines to farm fields to weapons manufacturing. That includes the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF), led by Gen. Abdel Fattah al-Burhan, and the Rapid Support Forces, led by a general known as Hemedti. Even before the two generals turned on each other in a civil war, the country’s citizens protested the way the military was handling gold mining.

In March 2023, protesters in Sudan’s Red Sea State called for the SAF to shut down a gold mine it operated within the Dordeib military base.

“We have been wondering how it is possible that mining plants have been established inside an army base, and why the army diverges from its real tasks and sets up commercial enterprises instead,” one protester told Sudan’s Radio Dabanga.

Hemedti has ties to the Russian mercenary Wagner Group, which began its own mining operations in Sudan under former dictator Omar al-Bashir. Wagner smuggles tons of gold out of Sudan each year to help Russia get around international financial sanctions imposed after the 2022 invasion of Ukraine. The smuggling costs Sudan millions of dollars in lost public revenue each year.

Sudan is not the only country with its military engaged in commercial enterprises. Such military-owned businesses are most prevalent in the natural resource sectors and in the extractive industries. In its report, “Military-owned businesses: corruption & risk reform,” Transparency International noted that the military’s privileged position in society “enables it to capitalize on its power and patronage networks.” Additionally, being in charge of border security, the military has the power to easily import and export goods “without being subject to state customs or inspections.”

SELLING OUT TO WAGNER

In the Central African Republic (CAR), President Faustin-Archange Touadéra has hired the Wagner Group to serve as his private security force, among other things. In exchange for its work, the group has gained direct access to the CAR’s natural resources.

Wagner regularly uses violence to seize and profit from natural resources in Africa.

“The story Wagner spins is that the mercenaries are there to train CAR soldiers and help them crush rebel groups that want to overthrow the president,” CBS News reported in May 2023. “The reality is that the Wagner Group has captured the country so completely that it can act with impunity, and it stands accused of using horrific violence to ensure there’s no competition for its revenue stream from local gold merchants.”

The details of projects in the CAR show that Wagner’s mining efforts are becoming increasingly profitable for the organization and create a pipeline of funding for Russia’s war against Ukraine.

“Wagner set up shop in CAR in 2018, creating a cultural center and striking several deals to help secure mining sites, including at the Ndassima gold mine located near the town of Bambari in the middle of the country,” wrote national security reporter Erin Banco in early 2023. “Since then, Wagner has turned the once-artisanal mine into a massive complex.”

As of early 2023, the mine encompassed eight production zones in various stages of development, with the largest believed to be more than 60 meters deep. Observers believe the group is building the site for long-term exploitation and has fortified it with bridges at river crossings and anti-aircraft guns at key spots. The Russians have made it clear that they don’t want any reconnaissance aircraft flying over it.

MISUSED RESOURCES

There are many reasons why natural resources don’t end up being a boon to national economies. In some parts of Africa, invading thieves and terrorists prevent countries from extracting their resources. In other countries, such as Burkina Faso, terrorists have taken over entire gold-mining operations. In West Africa, protected forests of endangered rosewood have been destroyed and shipped to China. Local officials are bribed to look the other way as the trees are cut down.

Rosewood is highly prized in China in the making of custom furniture. Relentless demand from Chinese manufacturers has turned rosewood into the most highly trafficked natural material in the world. Interpol estimated in early 2023 that rosewood was worth $50,000 per cubic meter.

China turned its attention to West Africa after depleting its own rosewood stocks. Environmental activists say China’s lust for rosewood drives a black market that is corrupting government officials and tribal leaders, undercutting international protections, and devastating the environment. According to Raphael Edou, Benin’s former minister for environment, rosewood poaching in Cameroon also weakens the rule of law there. Benin was an early target of the Chinese-driven rosewood trade.

“It’s almost as if Africa cannot deal with the Chinese on an equal footing,” Professor Abel Esterhuyse of the faculty of Military Science at Stellenbosch University in South Africa told ADF. “African nations cannot say, ‘Listen, you’re not going to exploit us.’ Africa needs to articulate using their own resources as a tool to manage their governments, as a tool of interest to allow other countries to compete for its commercial relations, as a benefit to society as a whole.

“It’s fascinating to me what China has done to the northern part of Namibia over the past 10 years in taking every piece of wood, all the trees,” he said. “They’ve also done it in the southern part of Angola. The problem is that it created a huge resentment amongst the people asking, ‘What are the Chinese doing with our own land?’ It creates this political economy between Africa and the rest of the world in a way that Africans don’t benefit from their own resources. It’s unbelievable.”

SUCCESS STORIES

Countries throughout the continent have shown the value of properly using their national resources, through private enterprise, for the good of their people. These mined and harvested assets have provide revenue streams and taxes to stabilize and improve civilian governments:

Côte d’Ivoire has enjoyed a strong and stable economic expansion for the past decade and has been described as “one of Africa’s underrated emerging markets.” The Nomad Capitalist website reports that the COVID-19 pandemic interrupted the country’s growth, though the economic forecast remains positive. The country’s natural resources include diamonds, gold, natural gas and oil. Other resources, such as iron ore, cement and nickel, remain largely unexploited. The country has a relatively stable political sector with strong growth predicted in the coming years.

Ghana’s natural resources include aluminum, bauxite, diamonds and timber. Ghana is the largest supplier of gold in Africa, producing about $5 billion to $7 billion annually. Ghana is considered one of the more stable countries in West Africa since its transition to multiparty democracy in 1992.

Namibia is one of the driest places in the world, with annual precipitation of about 27 centimeters. But it has large reserves of diamonds, copper and uranium. The country ranks fifth among African countries in diamond production. World Atlas reports that Namibia is the world’s fourth-largest producer of uranium, ranking behind Australia, Canada and Kazakhstan.

Namibia ranks fourth among African nations on the Democracy Index. According to Business Insider Africa, the country’s score “highlights its commitment to inclusivity, electoral processes, and civil liberties.”

Botswana is known for its wildlife, with 38% of its land set aside for national parks, reserves and wildlife management areas. The landlocked country of about 2 million people has been described by Business Insider Africa as “one of those quiet yet prosperous countries on the African plain.” Although it has a number of resources, its chief export, about 80%, is diamonds, making it second only to Russia in diamond production.

Esterhuyse cites Botswana as an example of a country that knows how to handle its resources.

“Here are some of the things they are doing right,” he told ADF. “They have a very strong bureaucracy in place. They have a healthy bureaucracy that is not only well educated, not only well skilled, but it can be trusted by the people and the state. I’m not talking about politicians here. I’m saying they have a mature, bureaucratic administration system.

“There is an institutional history in Botswana based on competency and merit,” he said. “To that, you add the security apparatus, which is no different than the rest of the state sector. The security apparatus is well funded, like 4% to 5% of [gross national product]. The security apparatus is well skilled, well trained and professional. And the security apparatus includes intelligence services as well. The intelligence services in many countries are often not spoken about, because often they are not coming to the table in terms of doing their job. That’s not the case with Botswana.”

Esterhuyse said that problems with exploitation are not unique to African countries.

“I don’t think Africa is any different from any other political entities in the world at large where you have an immature political system, where you allow politicians to capitalize on the opportunities that are available, where you don’t have a well-balanced and strong parliamentary system that asks the right questions,” he said. “Preventing exploitation has to do with governance.”