ADF STAFF

COVID-19 constantly shifts, adapts and mutates, all to help it spread. Those changes frequently affect the virus’s spike proteins, the keys it uses to unlock human cells.

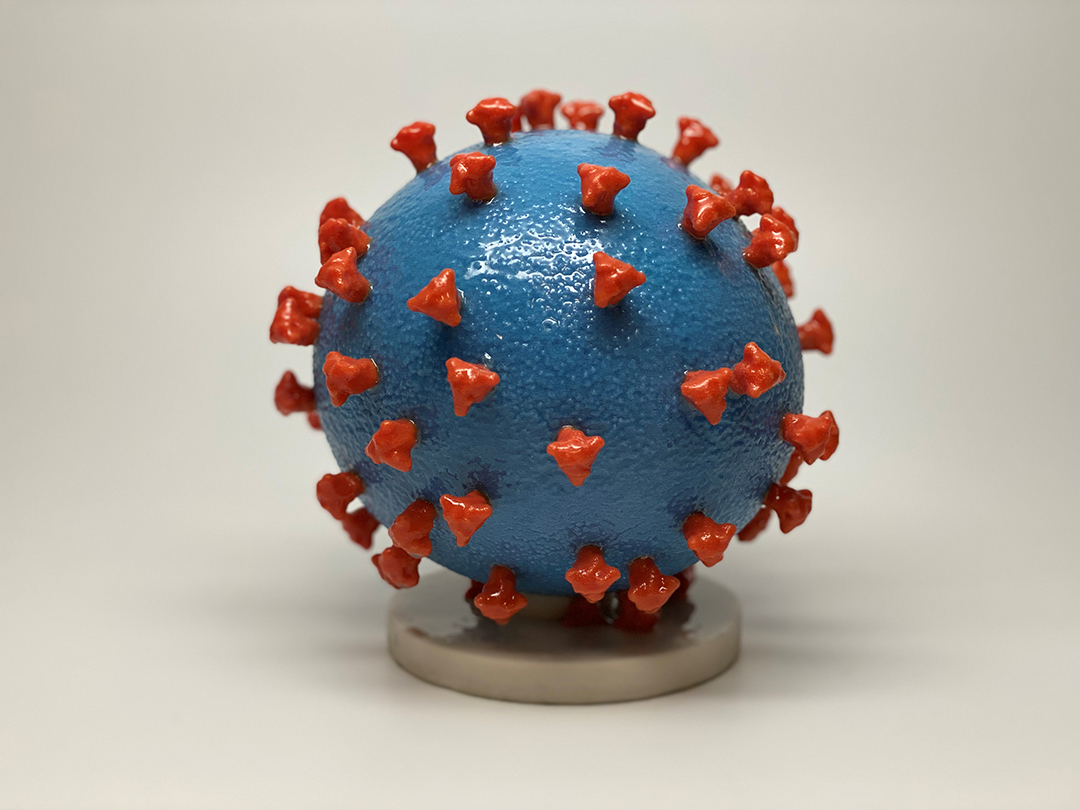

Illustrations of the COVID-19 virus typically show it as a ball covered with knobs. The knobs are spike proteins, bits of material the virus uses to pry open human cells so it can slip inside and begin replicating.

Each virus has two- to three-dozen spike proteins. Each spike is a potential key to unlock the cell. By mutating its keys, the virus increases its chances of success.

“Mutations in the spike proteins are of great interest,” Dr. Adrian Puren, acting executive director of South Africa’s National Institute for Communicable Diseases, recently told SABC television.

Each new COVID-19 infection gives the virus another chance to mutate — another chance to develop the spike protein that will bypass the body’s defenses. Although most mutations fail to produce an advantage, every now and then one appears that makes the virus stronger, faster and more capable of evading the body’s natural defenses.

Since the appearance of the alpha and beta variants in December 2020, scientists and public health experts have found themselves continually reacting to new variants.

Over the past year, researchers have detected more than a dozen variants that are worrisome enough to gain the attention of the World Health Organization (WHO). All variants receive scientific names involving letters and numbers. Those designated variants of concern or variants of interest because of their infectiousness or other factors receive Greek letter names.

African laboratories detected beta, eta, C.1.2, and the new B.1.640 and omicron variants.

The alpha variant first appeared in Europe before spreading to Africa. The deadly delta variant, which caused Africa’s third wave of infections in mid-2021 and killed more than 70,000 people, first was detected in India.

Scientists say that the country where a virus is detected is not necessarily its point of origin.

“It is difficult or impossible to find the origin of variants,” Dr. Tulio de Oliveira, director of CERI, the Centre for Epidemic Response and Innovation, told SABC.

So far, up to 45 African countries have reported the alpha, beta and delta variants. Often, the variants overlap in countries, according to Dr. John Nkengasong, director of the Africa Centres for Disease Control and Prevention (Africa CDC).

All notable variants have mutations in their spike proteins. In some cases, they have multiple mutations.

The C.1.2 variant is the most mutated variant scientists had discovered to that point. Scientists believe that was the result of the extended time it might have taken an immune-compromised person to fight off the virus. The B.1.640 variant was even more complex, adding mutations to seven spike proteins and deleting several others, according to the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control.

The B.1.640 variant raised alarms when it turned up among students at a school in France. France makes up 63% of B.1.640 cases, with the Republic of the Congo accounting for 15%.

Africa’s public health leaders continue to urge people to wear masks, wash their hands frequently, and avoid large groups and enclosed spaces to reduce the spread of COVID-19 in general and the emergence of variants specifically.

As the WHO and Africa CDC expand the continent’s ability to analyze COVID-19 infections at the genetic level, the likelihood increases that scientists will find more variants and more changes to the virus’s spike protein.

Although mutations create the potential that the virus will become more infectious, that’s not always the case. The eta and C.1.2 variants remain minor players in the continent’s COVID-19 fight.

Puren estimated that C.1.2 makes up less than 5% of cases in South Africa, despite its high number of mutations.

“That virus looks very different in terms of mutations, and yet it hasn’t taken off in South Africa,” Puren said. “I think we just we need to be cautious.”