ADF STAFF

Russian mercenaries have been linked to human rights abuses and have tried to profit off the chaos in the Central African Republic (CAR), one of the poorest countries in the world despite vast natural resources.

In March 2021, United Nations-appointed independent-rights experts alleged that the CAR’s recruitment and use of “private military and foreign security contractors” from Russia and Sudan were raising the risks of widespread human rights abuses.

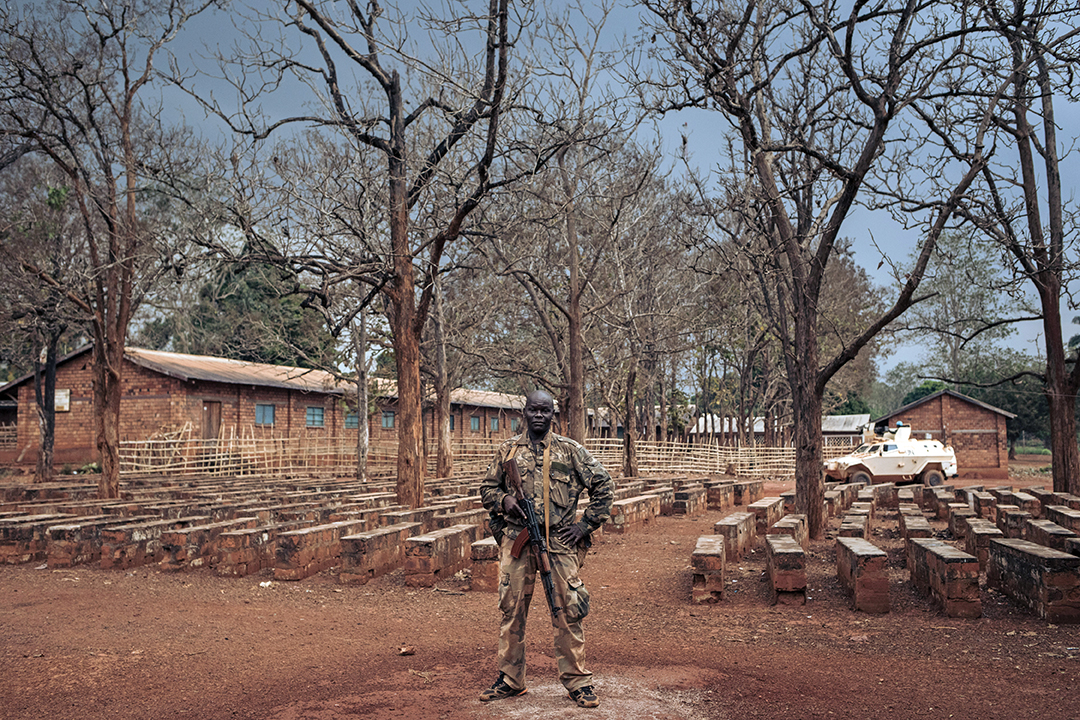

At the same time, the country’s president was using Russian mercenaries as his personal bodyguards. Russian mercenaries had contacts with some of the 15,000 peacekeepers involved with the U.N. Multidimensional Integrated Stabilization Mission in the Central African Republic (MINUSCA).

The rights experts, the U.N. reported, said that such private military personnel have been linked to reports of “mass summary executions, arbitrary detentions, torture during interrogations, forced disappearances, forced displacement of the civilian population, indiscriminate targeting of civilian facilities, violations of the right to health, and increasing attacks on humanitarian actors.”

One former government official told The New York Times in 2019 that Russian mercenaries flew private planes near a CAR site where they were training local Soldiers. They loaded the planes with diamonds, the newspaper reported. “Russian contractors were also digging up diamonds near the border with Sudan, according to the local officials and warlords.”

A HISTORY OF REBELLION

The country has seldom been stable since its independence in 1960, but it has been in a constant state of strife since rebels took control of the capital in March 2013. Rebel fighting in the country has forced nearly a fourth of its 4.5 million people to flee their homes. Rival militia groups control most of the nation.

Voters elected Faustin-Archange Touadéra, a former prime minister, as president in 2016. Touadéra was reelected at the end of 2020 in a vote in which some CAR citizens were unable to participate due to the violence. About 14% of the nation’s 800 polling stations were closed.

In the weeks leading up to the 2020 elections, U.N. experts charged with monitoring an arms embargo in the CAR cited an “influx of foreign fighters” into the country. The U.N. said that a series of clashes was fueled “by arrivals of foreign fighters and weaponry, mainly from Sudan.”

The election violence forced 120,000 people to flee for their lives, with half seeking refuge in neighboring countries.

The U.N. Security Council approved an increase of nearly 3,700 military personnel and police to MINUSCA in March 2021 to help reverse deteriorating security. A council resolution, adopted by a vote of 14-0 with Russia abstaining, brought the ceiling for military personnel to 14,400 and for police to 3,020.

The election in late 2020 may prove to be a pivotal moment in the nation’s history. Only months earlier, the country recruited nearly 1,500 new officers to its internal security forces — 800 police students and 550 gendarmerie students, including 138 women. In the weeks leading up to the election, rebel groups began attacking the country’s security forces. As Foreign Policy magazine noted, the international community was caught off guard as news spread of town after town falling to rebel groups.

“Within days, Russia sent to Bangui 300 ‘military advisors,’ then more troops and helicopters,” the magazine reported. “Rwanda deployed hundreds of troops not ‘constrained’ by U.N. rules of engagement; and MINUSCA received reinforcements, including 300 (Rwandan U.N. peacekeepers) stationed in South Sudan.”

The added manpower helped restore order in most towns. MINUSCA recaptured the town of Bambari, losing three peacekeepers in the process. The Central African Armed Forces (FACA), along with the Rwandans and a Russian private mercenary company retook the towns of Boali, Bossembélé and Mbaiki.

In 2021, Foreign Policy said, “ordinary citizens find themselves in even greater danger as the delicate balance of power shifts among local politicians, international actors and armed groups.”

Viola Giuliano of the Center for Civilians in Conflict told the magazine that “there are two defense forces.”

“The first is the presidential guard, which has privileged access to equipment and means,” she said. “The second, ‘normal’ FACA, is deployed outside Bangui in deplorable conditions. No fuel for patrol. Salaries not paid for months and rotations are often delayed.”

BUSINESS IN AFRICA

Russia’s interest in the CAR is part of a larger strategy — arms sales and expanded influence across Africa. Russia supplies almost half of the world’s arms exports to the continent.

Because of political instability and human rights violations, the U.N. imposed an arms embargo on the CAR and FACA in 2013. In December 2017, Russia obtained an exemption and supplied CAR with weapons and training.

Russia since has used this as an opening to take on a larger role in the CAR’s security and other government affairs. The United States Institute of Peace reported that Russia has a “direct avenue” to the CAR government through Valery Zakharov, a former Russian intelligence official, who has served as Touadéra’s national security advisor.

In 2019, Touadéra traveled to Russia to participate in the first Russia-Africa Summit, a gathering of hundreds of African leaders that the institute said was meant to “highlight and secure Russia’s expanding influence in the continent.”

After meeting with Russian President Vladimir Putin, Touadéra reportedly asked for more Russian weapons shipments. He also said he would consider hosting a Russian military base in his country.

“Russian personnel in CAR, with additional troops in nearby Sudan, provide state actors to direct activities for Russia’s benefit in rebel-controlled areas with great natural resource value,” wrote researcher Kyran Goodison in a study titled “Russia in the Central African Republic: Exploitation Under the Guise of Intervention.”

“The impact of controlling CAR’s resources is enhanced by Russian seaport access in Sudan. Combined, internationally approved Russian arms and personnel for training create the means for Russia to exploit CAR’s conflict,” Goodison wrote.

WAGNER GROUP INVOLVED

The Russians in the CAR include the Wagner Group, an armed Russian private military company controlled by Putin ally Yevgeny Prigozhin. It is believed to be a thinly disguised arm of the Russian military, giving Russia deniability of involvement in other countries’ affairs. The group has meddled in the affairs of countries throughout Africa and other parts of the world and has operated in at least 20 African nations.

The Wagner Group acts as a security provider in the CAR and has a major role in training the presidential guards and the Army. Some Wagner Group mercenaries are based in Berego Palace, which, in the 1970s, was the headquarters of Jean-Bedel Bokassa, then the country’s self-claimed emperor, and has now been turned into a military base.

“Private military contractors like Wagner Group, funded through local mineral concessions, plant a Russian flag in Africa,” Foreign Policy reported. The CAR, “in turn, receives hands-on assistance for its armed forces that no other country is willing to provide.”

The military news website Special Operations Forces Report wrote in 2020 that there were 180 Russian “official” army instructors based in the CAR, along with as many as 1,000 Russian “civilian” contractors from the Wagner Group in the country.

A NEED FOR REFORM

Armed rebel groups are one of the main drivers of instability in the CAR. They have forced people from their homes, disrupted trade routes and blocked humanitarian aid. Before MINUSCA deployed, there were three main recognized armed groups in the CAR. Now there are 14.

The country is in a state of crisis and is requesting outside help. Foreign Policy said the country received only 65% of its funding needs in 2020 and only 51% of its COVID-19 funding needs.

As the country tries to rebuild its Armed Forces and embark on security sector reform, observers point to mercenaries in the country as a hindrance, not a help.

“CAR is much more than a ‘security vacuum’ in the region,” reported Foreign Policy. “In fact, many of the sources of the country’s instability come from beyond its borders. But the increasingly international nature of the conflict, and the focus on military solutions, will continue to overshadow the socioeconomic roots of CAR’s insecurity.”