ADF STAFF

Threats in the coastal waterways of Africa have multiplied in recent years. Smuggling, piracy and oil bunkering all occur in the shallow waters that snake from the ocean to the interior of the continent. These threats cannot be stopped by large, blue sea naval vessels.

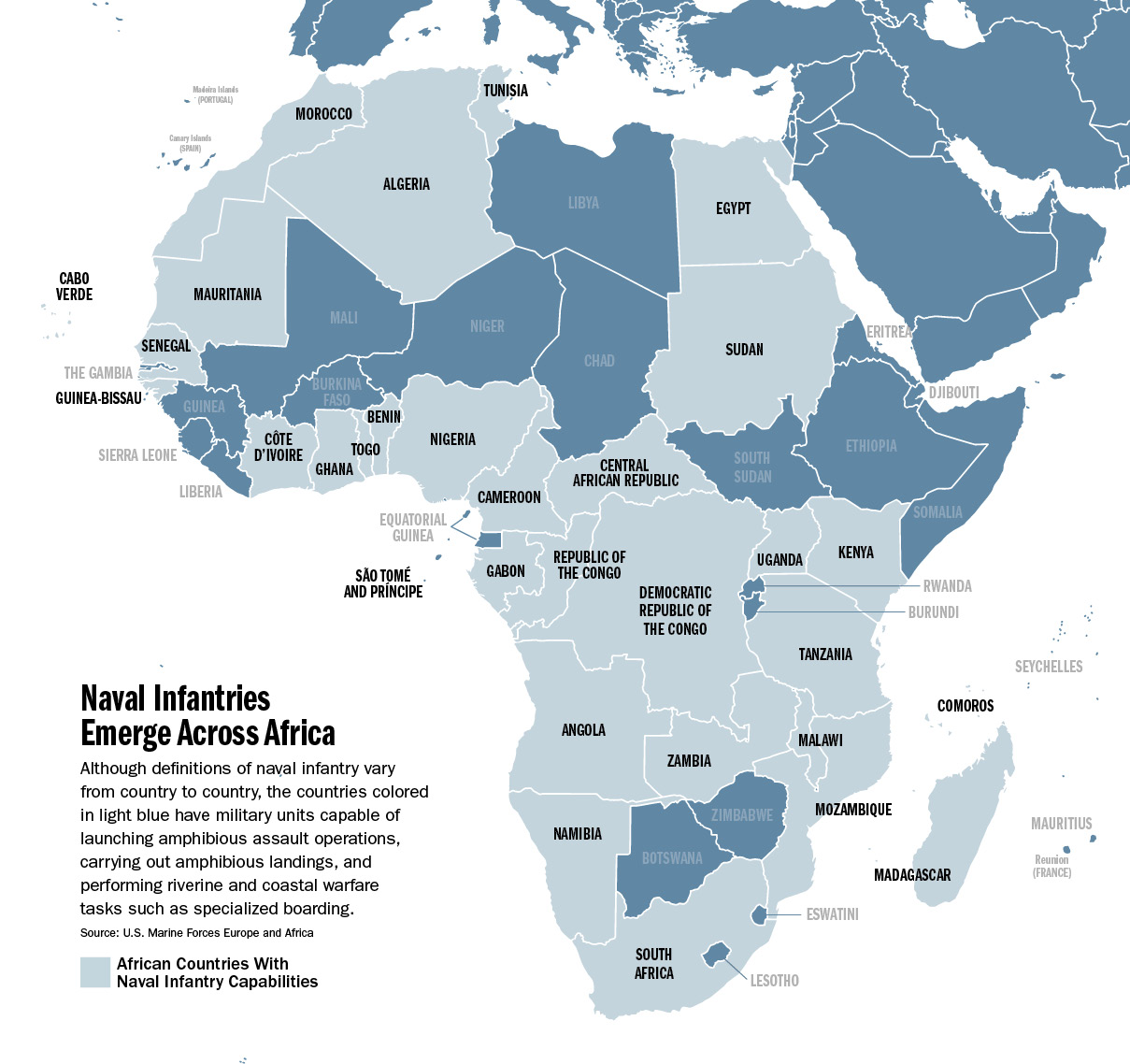

In response, navies are evolving. They are investing time and money in agile and adaptable infantry units. These highly trained units go by different names: In Senegal, they are marine commandos; in Nigeria they are the Special Boat Service; and in Angola they are Fuzileiros. They are designed to be nimble, capable of protecting offshore energy infrastructure or pursuing traffickers in mangrove swamps.

Speed, they say, is their calling card. The element of surprise, rigorous training and a sense of purpose help them get results.

“These are the principles that enable a small entity to take on attacks which, traditionally, were conducted by a larger entity –– sometimes three times its size –– and achieve results,” said Lt. Cmdr. Seth Dzakpasu, commander of Ghana’s Special Boat Squadron.

With many countries looking to grow the blue economy –– commerce connected to oceans and riverways –– proponents believe the naval infantry must play a role in protecting it. They can do so by embracing new training models, new technology and new partnerships.

“It is time to invest in naval infantry,” said retired Senegalese Navy Rear Adm. Samba Fall, one of the early members of his country’s marine commando unit, which dates to 1980. “In many African countries the riverine and maritime surface area is larger than their land area. The new threats are exploiting this marine and river space. So we need to expand in terms of numbers and embrace new technology.”

Created to Fill a Gap

In the early 2000s, the Niger Delta had become lawless. With more than 3,000 creeks and hundreds of tiny islands, armed militias had plenty of places to hide. In 2007, militants kidnapped more than 150 people and launched many more attacks on oil infrastructure. Traditional naval vessels and training proved inadequate to contain the threat.

In 2006, Nigeria created the Special Boat Service (SBS), an elite unit built for asymmetric warfare in a riverine environment.

“The Navy saw a challenge,” said Capt. Olayinka Aliu, commander of the Nigerian Special Boat Service. “If you’re going to have the special operations forces to operate effectively, within the uniqueness of the Nigerian maritime environment, then they must continue military operations beyond the traditional maritime environment into the riverine area. Riverine operations are mostly joint operations, and you need some sort of infantry capabilities which conventional naval forces did not have.”

Nigeria modeled its SBS after the U.S. Navy Seals and received help developing training modules from them. The SBS’s 24-week Basic Operating Capability course is notoriously rigorous with candidates forced to endure sleep deprivation and demonstrate immense swimming and endurance capabilities. The SBS has expanded to include courses on jungle warfare, desert warfare, amphibious operations and riverine operations. A training squadron rotates constantly to offer four- to six-week courses to keep skills sharp.

All of this is in the interest of staying ahead of maritime crime.

“Things are changing. The maritime crime is constantly mutating. When you have a strategy, something else always comes up,” Aliu said. “Crime will continue to mutate, and you just have to be ready as a naval infantry; this is how you stay 10 steps ahead of the criminal.”

As of 2022, the SBS was involved in six operations ranging from Operation Hadin Kai in the northeast to defeat Boko Haram and related groups, to Operation Hadarin Daji against bandits in the northwest. The SBS also has sent trainers to Chad and Niger to help develop boat units to fight extremists and traffickers in the Lake Chad region.

Aliu said the mission set of the SBS is expanding. Now, most of its work is on land. It has designs on changing its name and upgrading to a full-fledged special operations command. In Nigeria, he believes, the naval infantry is filling an important security gap.

“What happens on land has a way of shaping events at sea,” Aliu said. “You’ll find that the pirates do not live at sea; they come from a coastal community. There is a need to close this gap between the maritime environment and the riverine environment. And this is where the naval infantry comes in.”

Expanding Education

As countries are asking naval infantries to take on new tasks, they see the need for continuing training and education. But keeping skills sharp is a challenge.

Ghana created its Special Boat Squadron in 2016. It specializes in opposed boarding situations and other hostile scenarios such as hostage rescue. Potential squadron members are volunteers from within the Ghana Navy who are screened and shortlisted to attempt the six-month course.

Dzakpasu, commander of the Ghana Navy Special Boat Squadron, said the course is “grueling” and “academically daunting.” “The SBS course is in phases,” he said. “It is designed to first condition you to work in small groups and move rapidly; then the other phases develop your mindset, the mindset to know the possibilities that a standard military unit might think is impossible.”

Throughout their career, operators will take upgrade courses. All operators are expected to gain the skills to become instructors so they can train others.

This constant training, Dzakpasu said, makes a difference. “It’s not about getting more sophisticated equipment but making use of whatever you have to the best of your capabilities to achieve your goals,” he said. “It also gives you the backbone to plan to have definite missions, so you don’t take on a mission that is far beyond your capability.”

Across the globe, training is being updated. Marine training is becoming more interactive, tailored to the individual and designed to ensure that the trainee retains knowledge throughout his or her career.

More noncommissioned officers are receiving strategic and leadership training so they are ready to make decisions when leading small squads. The concept of creating the “strategic corporal,” an NCO who is empowered to lead like an officer, is gaining traction.

“The threat is ever-evolving; you are more than likely fighting in a very dispersed nature,” said Maj. Trevor Hall, who develops training programs for the U.S. Marine Corps. “Because you’re more spread out, you’re not going to have officers around to make every decision. Those decisions are made at the squad level or below.”

Senegal is one of the countries investing in education. In January 2022, the country opened its École de la Marine Nationale, a naval school with an emphasis on giving Sailors access to cutting-edge courses.

“Human resources,” are the “heart of the Navy,” said Rear Adm. Oumar Wade, Senegal’s naval chief of staff. “For us, the main pillar of security is instruction, training and maintenance of the skills acquired at school.”

Emerging partnerships were on display during the first in-person Naval Infantry Leadership Symposium-Africa in Dakar on July 7 and 8, 2022.

Naval leaders from 22 African countries and eight other countries exchanged best practices and discussed common challenges. It ended with the signing of a charter in which all countries pledged to continue sharing information and cooperating on issues of joint interest.

West Africa has made major strides in regional cooperation. In 2023, the Yaoundé Code of Conduct will mark its 10th anniversary. The security architecture created by it now allows coordinated patrols and the free exchange of information to track and intercept ships in the Gulf of Guinea and beyond.

Symposium attendees noted that interoperability among navies remains a challenge with language barriers, doctrine, laws and equipment sometimes making partnerships difficult.

But, Wade said, “trust is the key word,” noting that trust has been built through more than a decade of joint exercises and cooperation.

“The willingness to create interoperability is there, but it’s our officers who are constantly meeting who will make this path possible,” Wade said.

Some new partnerships cross oceans. Brazil’s Marine Corps has created an advisory group in Namibia and São Tomé and Príncipe and is conducting training events in other African countries. Sea and War Capt. Andre Guimaraes of the Brazilian Marine Corps spoke at the symposium and said training in different environments is vital to the development of a Marine. He encouraged leaders in attendance to lean into training and said that Brazil’s demanding riverine course in the Amazon is open to Marines from across the globe.

“A lot of times we focus too much on equipment; we all want the best vessels,” Guimaraes said. “But we just need adequate equipment with an engaged operator with constant training. All the technology in the world doesn’t amount to much if you don’t have, in the unit, Marines ready to be leaders.”

Fall, with decades of experience, sees a global community of naval infantry leaders emerging in Africa with a shared purpose. He hopes to see the exchange of knowledge continue not only at the strategic level, but at the tactical level.

“It’s essential. We have to exchange,” he said. “Right now, it’s not countries acting alone; we need countries working together to face these threats. We need coalitions. We have to be on the side of those looking to do the right thing, the moral thing, and the democratic thing. To face threats that are emerging all the time.”