ADF STAFF

Modern fighter jets are marvels of power and complexity. Armed with air-to-air missiles, they can reach speeds of 1,600 kilometers per hour. They are also stunningly expensive. The current generation of fighter jets start at about $100 million each, and it is estimated that each plane will cost $1 billion in operational expenses and maintenance over the course of its optimal life span.

There’s also the matter of usefulness. In anything less than air combat and missile strikes, a fighter jet is overkill. Since the end of the Cold War, air forces have seldom flown in heavily contested airspaces, and instances of facing advanced military rivals with sophisticated defense systems and avionics are extremely rare.

These days, warfare is largely asymmetric, waged against insurgents and terrorists. This is particularly the case in several parts of Africa. There is no air-to-air combat. For this kind of warfare, smaller, more maneuverable craft are needed. These counterinsurgency, or COIN, aircraft often were designed to be trainers for pilots. They cost only a fraction of the price of a fighter jet and are far easier, and less expensive, to maintain. They can be adapted to new uses in light attack, reconnaissance and as utility “pickup trucks of the sky.”

Aviation website Key Aero says that light attack aircraft are a “cheap and ready source of airpower” for cost-concerned countries facing insurgencies. The per-hour operating cost for such aircraft typically is about $2,000, or 2% to 4% of the cost of advanced fighter jets. The initial cost also is lower, Key Aero noted, with one baseline COIN fighter starting at about $10 million.

This one is from the South African Navy fleet.

Nigeria, with one of the largest air forces in Sub-Saharan Africa, was one of the first to recognize the usefulness of the smaller planes.

“With its extensive combat experience, first in Liberia as part of the Economic Community of West African States monitoring group peace-keeping force, and then in the long war against Boko Haram, the Nigerian Air Force soon found that its frontline fast-jet fighters were much less useful for close air support than its Aero L-39 and Dassault Alpha Jet advanced trainers,” reported news site Times Aerospace. “The latter have formed the backbone of Nigeria’s air campaign against the Islamist insurgent group, while the type has also been used operationally by Cameroon, Egypt, Morocco and Togo.”

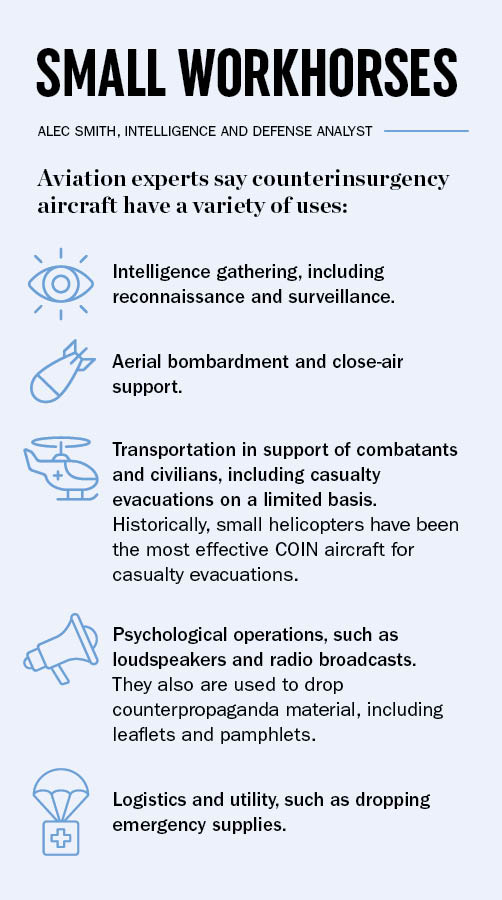

Alec Smith, an intelligence and defense analyst for Grey Dynamics, noted that the United States reportedly has considered scaling down its drone program with an eye toward using manned COIN aircraft.

“As the war between nation-states becomes less prevalent, and localized insurgencies become more problematic and difficult to manage, COIN aircraft will play a large role in mitigating and limiting the scope of insurgent operations in the future,” he wrote.

These COIN planes are not always based on trainers. The U.S. Air Force in 2022 announced that it had chosen the AT-802U Sky Warden, produced by L3Harris Technologies and agricultural aircraft maker Air Tractor, to take on its Armed Overwatch mission, conducting counterterrorism operations and irregular warfare in places such as Africa. Forbes magazine reported that the Sky Warden is based on a single-prop crop-duster.

The Sky Warden was chosen for its large payload; its ability to fire missiles, drones and small munitions; and its ability to carry multiple sensors and up to seven tactical line-of-sight and beyond line-of-sight radios, Forbes noted.

COIN aircraft are not just fixed-wing manned planes; drones and helicopters also have been used in asymmetric warfare. Helicopters, however, have obvious vulnerabilities to groundfire, and drones tend to be limited by line-of-sight issues.

Smith notes that helicopters have been heavily used as COIN aircraft but have limitations.

“Despite appearances, the rotors are actually incredibly brittle,” he told ADF in an email. “Small arms fire can prove fatal to a helicopter, and because helicopters tend to fly lower and slower than fixed-wing aircraft, they are at an increased exposure to this potentially fatal ground fire. Helicopters certainly play important roles in COIN operations, such as enhancing air mobility and casualty evacuation, but they are only as useful insofar as the circumstances permit.”

saw service throughout the world. Some were reportedly still in service as recently as 2016.

BEGINNINGS OF COIN CRAFT

The use of aircraft in counterinsurgencies dates almost to the dawn of aviation. But historians say that modern COIN planes date to the early 1950s, when the U.S. began experimenting with trainer aircraft in Korea and years later in Vietnam.

“In Korea, U.S. airmen flew armed versions of the North American T-6 Texan piston-engined trainers dubbed ‘Mosquitos,’ primarily for artillery spotting and forward air control,” wrote Robert Dorr for The Year in Defense: Aerospace Edition, in 2010.

Over the years, military experts have listed the accepted standards for successful COIN aircraft. They are:

The aircraft must be durable, capable of enduring long periods of use without servicing the engine or avionics. They must be cost-effective to buy and maintain.

They must be capable of getting airborne quickly in emergencies.

They must be tough enough to survive rough landings on difficult, unpaved terrain. Ideally, they should be capable of executing short takeoffs and landings from makeshift runways.

They must be simple to pilot. Simple operating procedures make it easier to train pilots. The simplicity of operation also makes it easier to maintain the aircraft — a critical point in keeping an air fleet operational.

Such aircraft must have the capability of low “loitering” speeds, combined with good range and fuel consumption.

They must be able to access remote areas rapidly while supporting troops with reinforcements and supplies.

COIN programs became increasingly important around the end of the 20th century when asymmetric wars became the norm. Some experts contend that drones

could replace manned COIN aircraft in the future.

Key Aero says it’s too soon to assume that drones eventually will replace COIN planes: “For one thing, drones are not necessarily the ‘cheaper option’ as commonly assumed. A recent report from the … Center for Strategic and International Studies noted that drones can cost as much as manned aircraft in the long run. The annual personnel costs for an ISR MQ-9 Reaper [drone], for instance, run at around $3 million.”

Doug Barrie from the International Institute for Strategic Studies told Key Aero that cost comparisons between drones and manned COIN craft can be misleading. Initially, he said, a COIN manned plane is going to be more expensive. “But that doesn’t take into account the training, the satellites you need to sustain in orbit for a [drone] to function, or the back-end support for the operation and exploitation.” And, he said, with a drone, “unless you’ve got a satellite link, you’re limited to a direct line of sight data link. You need to invest in a satellite capability or get someone to do that for you.”

Smith told ADF that it is “almost certain” that drones will dominate the air domain of counterinsurgency operations in the future, but there is still a need for light attack aircraft.

“This does not necessarily mean that light, manned aircraft won’t have a place going forward; it just means that they will be significantly less prevalent,” he said. “Manned aircraft will still be the primary tool for operations in contested airspace. Manned aircraft are useful when a certain degree of instant human intervention in the decision-making process is needed. Manned aircraft tend to be faster, so when rapid response is needed to a developing situation, drones are really not the best option.”

South African Company Producing New COIN Aircraft

ADF STAFF

The first Mwari surveillance and precision strike plane, originally known as the AHRLAC, has been spotted in Mozambique, sporting Mozambican markings.

DefenceWeb reported in March 2023 that the plane, which can be used in counterinsurgency or COIN operations, was spotted in Cabo Delgado province. Flight tracking data showed it flying around Nacala at the end of January 2023.

AHRLAC is short for advanced high performance reconnaissance light aircraft. DefenceWeb reported that it is the third AHRLAC built, after two prototypes, and is one of two preproduction aircraft. It first flew in April 2022.

The aircraft are being produced by Paramount Aerospace Industries of South Africa. Paramount in September 2022 said that four aircraft were on the production line at the Wonderboom Airport factory near Pretoria, and there were orders for nine of the aircraft from two customers. The aircraft are designed to compete with other small propeller-driven craft, particularly the successful Brazilian-made Embraer A-29 Super Tucano. There are more than 260 Super Tucanos in service around the world, including in Mauritania and Nigeria.

The Mwari has been under development for more than a decade. It is the first newly designed manned military aircraft in South Africa since the Rooivalk attack helicopter first went into service in 1999. Production was delayed in February 2019 after problems that included contractual, intellectual property and funding disputes. A rescue plan was developed, and production resumed in September 2022.

The Mwari is marketed as a relatively inexpensive alternative to high-end military aircraft for surveillance, maritime patrol and counterinsurgency operations. It also can be used for training. It has a service ceiling of up to 9.5 kilometers and offers a maximum cruise speed of 460 kilometers per hour, a mission range of more than 1,000 kilometers with ordnance, and an overall flight time of up to 6.5 hours.

Company officials say the aircraft also offers a short takeoff and landing capability, with retractable landing gear optimized for semi- and unprepared airstrips or sites. The aircraft features an unusual twin-boom, single-pusher engine and high-mounted forward-swept wing configuration. The company announced plans to sell the planes for about $10 million each, which is comparable to similar COIN planes sold in other parts of the world.

The website The National Interest has reported that the Mwari is being marketed specifically to African countries. The website quoted the company as saying, “The types of threats that countries around the world face has changed significantly over the last few years. Many of the threats being faced do not justify the operating cost of fast-jet fighters.”

The company also has plans to build a second plane, the Bronco II, which is designed to be rapidly disassembled, transported and reassembled in the field by a small crew. The company plans to build the Bronco II in Crestview, Florida, in the United States.