In the Senate chamber in Abuja, Nigeria, four nominees to lead military service branches took turns making the case that they were fit for the job. Each presented his credentials and outlined a vision for improving security in the country.

“Under my watch, the armed forces shall continue to serve the Nigerian people dutifully and in line with the Constitution of the Federal Republic of Nigeria and other extant laws of the federation,” Chief of Defense Staff Maj. Gen. Christopher Musa told senators in July 2023.

Afterward, senators questioned the nominees for three hours before confirming all four.

This might seem like a mundane process, but it embodies a vital principle: civilian control of the armed forces.

The principle that civilians should control the military dates back hundreds of years. Countries that embrace it have determined that an accountable and apolitical military is best able to provide security without falling for the temptation to grab power.

This and other concepts were enshrined in the African Union charter in 2007, which calls for “constitutional civilian control over the armed and security forces to ensure the consolidation of democracy and constitutional order.”

Despite a rash of recent coups, polls show a strong preference for civilian rule across the continent. According to an Afrobarometer poll from 2021, 75% reject military rule and 69% prefer democracy to any other form of government.

In countries that require civilian control, decisions about how to define threats and develop security strategies are made by elected representatives of the people. Civilians also make decisions about how the security sector should be staffed and funded, said Dr. Ibrahim Wani, a Ugandan diplomat who served as the director of the Human Rights Division at the U.N. Mission in South Sudan.

“All of the key policy decisions are to be made by the civilian component,” Wani said during a 2022 lecture at the Africa Center for Strategic Studies (ACSS). “The role of the military is very, very specifically defined. It is to give advice to civilian authorities in the formulation of those strategies and policies.”

Wani pointed to three mechanisms that solidify this control:

Formal mechanisms: Documents such as the constitution and “national defense act” legislation outline the duties and limits of military power. Elected or appointed members of the national security council, legislative bodies and cabinet members, such as the minister of defense, ensure that these documents are respected.

Monitoring and oversight: Civilian officials audit and investigate military activities and spending. Parliamentary committees and the media also play a role in monitoring the armed forces.

Professional norms and standards: Through recruitment, professional military education, training and promotion, the military instills the core values of an apolitical stance, loyalty to the constitution and subordinance to civilian authority.

A Winding Road

As countries transitioned from colonialism to independence, full civilian control of the military was sometimes called the “forgotten landmark” on the road to a functioning state. It rarely was a straight path. Countries such as Ghana and Togo experienced military coups in their first post-independence years as civilian presidents tried to rein in and reform the armed forces. By 1987, half of the continent’s countries were under military rule. Often, militaries viewed civilian oversight as a nuisance.

“In some other new independent countries, the military saw the civilian control as an unnecessary intrusion into the military sphere of competency,” wrote Col. Kemence Kokou Oyome of the Togolese Armed Forces. “Neither the military nor the civilian authorities did know their respective roles in the new national setting.”

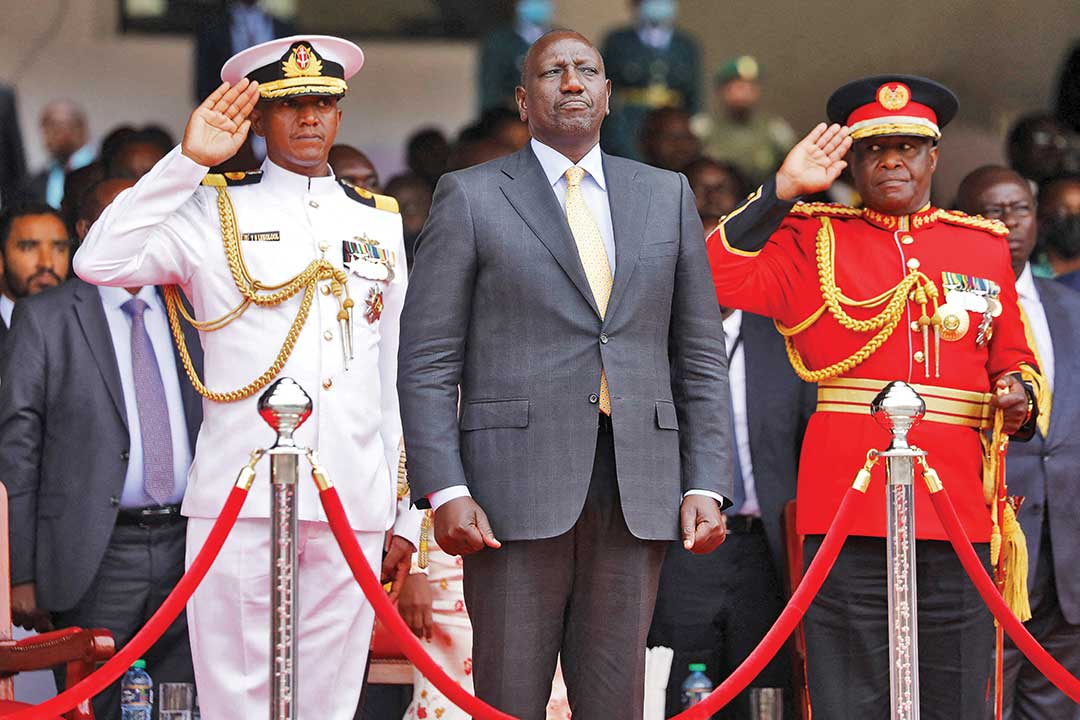

Over the years, countries have moved to strengthen the civilian rule principle. Kenya’s 2010 Constitution calls for national security to be “subject to the authority of this Constitution and Parliament.” It also calls for integrity, accountability and oversight measures.

In South Africa, after the transition to democracy, the country adopted a 1996 Constitution that stressed civilian control with multiparty parliamentary committees given oversight of all defense and intelligence matters.

Wani said the concept is widely accepted today even though, in practice, it is “a lot more give and take” than a hard and fast rule.

As countries look for ways to strengthen civil-military relations, experts say several areas are essential.

Put security forces in a position to fulfill their constitutional duties: Breakdowns in civil-military relations can occur when the armed forces are used in ways that are not provided for by the constitution. Judy Gitau, a Kenyan lawyer and regional coordinator for Equality Now, said this often happens in response to terrorism or domestic instability. The military is deployed domestically, often without approval by the national assembly, and is asked to take on a mission outside of its mandate.

“The way the military is structured doesn’t lend itself to law enforcement,” Gitau told ADF.

In the Kenyan Constitution the military can be deployed domestically only in cases of natural disaster or for peacekeeping. In these cases, the deployment must be authorized by the parliament and limited to a defined period.

“The military serves a military purpose; the exceptions are there in law, such as the military can use its muscle in the event of conflict or in the event of disaster,” she said. “This is when they can come from the barracks, but they shouldn’t be used for day-to-day law enforcement because they aren’t built for it.”

Too often, Gitau said, the military is asked to take on roles such as crowd control, detaining suspects and gathering evidence that should be handled by police.

“Once that line is blurred, it becomes easy for the administration of the day to use or even misuse the military and breach the civil-military relations as they should be,” Gitau told ADF.

Improve transparency: Civilian oversight is only possible with access to information. A lack of transparency about military affairs can lead to corruption. One highly publicized example is payments to “ghost soldiers” that exist on paper but not in real life.

“Information is essential to the exercise of civilian oversight by the executive, legislature, judiciary, and citizens,” wrote Godfrey Musila, a researcher and former commissioner to the United Nations Commission on Human Rights in South Sudan.

Musila said that, since 2000, 19 African countries have passed legislation strengthening access to information. In 2012, the AU Commission on Human Rights and Peoples’ Rights developed a model law for this purpose.

Still, Musila said, access to information in the defense sector lags behind other areas of government and hinders civilian oversight. Without transparency, corruption can flourish, and the military can be used in ways that are not in the public interest.

“The challenge is that in the vast majority of states on the continent, the security sector traditionally operates in a culture of secrecy,” he wrote. “‘National security’ is often improperly deployed as an all-trumping consideration; once invoked, it throws up a veil that forestalls any kind of scrutiny of what government does.”

Strengthen Institutions: When soldiers overthrow the government, they usually justify their actions by pointing to inadequate or corrupt civilian leadership. Gitau said there is a desperate need to improve judicial and democratic institutions so civilians never feel the need to support a coup or nondemocratic transfer of power.

“Systems must work, people should know that they can change in the next election, and they needn’t feel that the only saving grace is the military,” she said.

Parliamentary committees that oversee funding and staffing of the armed forces can be strengthened. In many African countries, parliaments have a high turnover rate and are not viewed as a credible counterbalance to the executive branch. Dr. Ken Opalo, a Kenyan-born academic who teaches at the Georgetown University School of Foreign Service, believes stronger parliamentary oversight would improve military accountability.

“Parliamentarians need to play a bigger role in overseeing the funding of the security sector in their countries but also providing input into the policies that the security sector implements because they know their constituents best,” Opalo said during an ACSS forum on accountability.

In the best cases, parliamentarians develop a rapport with military leaders that allows for a two-way discussion about defense priorities and threats facing the country. “That requires trust and constructive dialogue and engagement as opposed to confrontational postures that are common in many legislatures,” Opalo said.

When operating properly, the military offers advice and expertise but remains under the supervision of civilian leaders who act on behalf of the public. This leads to security priorities that address the public’s most pressing needs.

“The message here is strengthening institutions for purposes of accountability, governance and rule of law,” Gitau said. “That way there are proper channels and proper avenues that allow civilians to express their views, hold leaders to account, but more importantly in the question of civil-military relations, that ensures that they remain the principle and the miliary remains the agent.”