Special Units in West Africa Bring Together Agencies to Share Information and Resources

ADF STAFF

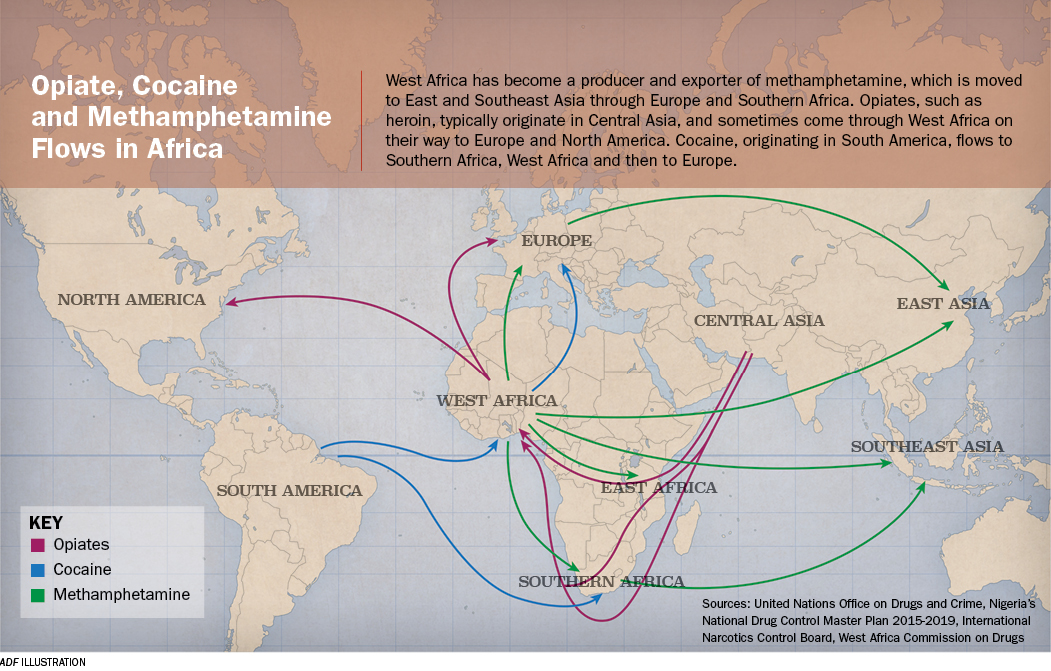

Africa stands as a transit point in a global drug trafficking network that funnels cocaine and other drugs into Europe. The drugs come into West Africa, usually from Brazil, and land in one of several nations, such as Cape Verde, The Gambia, Ghana and Nigeria. From there, the product is moved via air, land and sea toward its final destination.

A major drug shipment intercepted in Mali in 2016 followed this trend. The investigation began in May 2016 when Mali’s Central Office for Narcotic Drugs (OCS for Office Central des Stupéfiants) confiscated 2.7 tons of cannabis in Bamako. Authorities also arrested several people in Bamako and Accra, Ghana, where the drugs originated, according to the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC).

Officials found the drugs on a vehicle whose driver was paid $230 per trip between the two capitals, well above the regional monthly salary. The investigation continued, and in October 2016, Malian authorities arrested the drug ring’s alleged kingpin. Agents from the OCS and a similar agency in Senegal shared information, resulting in the arrest in Niamey, Niger.

Officials found the drugs on a vehicle whose driver was paid $230 per trip between the two capitals, well above the regional monthly salary. The investigation continued, and in October 2016, Malian authorities arrested the drug ring’s alleged kingpin. Agents from the OCS and a similar agency in Senegal shared information, resulting in the arrest in Niamey, Niger.

Authorities credited two things for their success in smashing the network: information sharing and ongoing training. Experts agree that success will depend largely on African nations’ ability to do both successfully, among their own national agencies and with their neighboring countries.

A fairly new effort in West Africa has further developed interagency cooperation, and the work is paying off.

THE PROBLEM IN WEST AFRICA

A 2014 report published by the West Africa Commission on Drugs (WACD) says cartels have joined with local partners to make the region a transit route for moving drugs from South America to Europe and to North America from Asia. Traffickers have moved beyond marijuana and cocaine and are now dealing in synthetic drugs, such as amphetamine-type stimulants (ATS), according to the report.

The first ATS labs to be dismantled in the region were in Guinea in 2009, according to a 2016 UNODC report. Nigeria’s National Drug Law Enforcement Agency has dismantled at least a dozen since mid-2011. ATS seizures in West Africa increased by 480 percent from 2012 to 2013, and authorities in Côte d’Ivoire confiscated 86 percent of the 1,414 kilograms seized during that time.

Nigerian organized crime groups often are at the forefront of cocaine trafficking and now are “on par with Latin American groups in their ability to source, finance and transport bulk quantities of cocaine from Latin America to Africa, Europe and elsewhere,” according to the 2016 “EU Drug Markets Report: In-Depth Analysis.” Nigerian gangsters also are among the most active groups involved in global methamphetamine trafficking.

REGIONAL COOPERATION

Illicit trafficking, including drugs, continues to be a major problem in West Africa. The presence of such crimes threatens and destabilizes social and political institutions. Much of the region has been plagued with violence and civil war for years. Exacerbating that problem, according to UNODC, are differences in language, national rivalries, a lack of technical communication capacities, and knowledge and training deficits among regional law enforcement agencies.

“Such forms of transnational organized crime can only be fought by proactive and well-coordinated law enforcement agencies, utilizing all the information and resources available within a country, as well as international forms of operational cooperation,” according to the UNODC.

The West Africa Coast Initiative (WACI) is the result of collaboration among UNODC, other U.N. offices and Interpol working to support Economic Community of West African States goals to address drugs and organized crime. WACI’s aims include:

Building capacity for better national, regional and international law enforcement cooperation.

Increasing regional and national capacity building, primarily in Côte d’Ivoire, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Liberia and Sierra Leone.

TCUs are at the heart of efforts to curb drug trafficking in West Africa. The first opened in Sierra Leone in 2010, and Guinea-Bissau and Liberia established TCUs in 2011. The UNODC is providing ongoing advisory assistance for the establishment of a functional TCU in Côte d’Ivoire as well. Leaders have been nominated for its center, and it could open by the middle of 2017.

“We’ve seen very good operational results that have been achieved,” said Pierre Lapaque, regional representative for UNODC’s Regional Office for West and Central Africa, in Dakar, Senegal.

The plan is to add a TCU in Guinea as well, but government negotiations still are underway, and donor funding has not been secured. It is not likely to open this year, Lapaque said.

The TCUs allow a wide variety of law enforcement and security agencies to share space and work together. National police forces, gendarmes, national intelligence personnel, customs, immigration, port and airport authorities, and anticorruption officers all can be part of TCUs. “It’s the call of the individual country to decide which agencies should be part of the TCU,” Lapaque said.

The thinking is that having various agencies represented together will avoid the “silos” that keep information from being shared. Breaking down the walls of these silos is the main purpose of the TCUs. That brings results, Lapaque said, as staffers start to trust each other. Information also flows from various agencies into the TCUs, where it can be analyzed, disseminated and used to conduct operations, either by the TCU itself or by TCU member agencies. The process can be slow, but things are improving, and results are evident.

Guinea-Bissau’s TCU has investigated more than 70 cases and prosecuted 83 people. Liberia has handled 59 cases and arrested and prosecuted 59 people.

So far, TCUs have operated nationally and regionally, and that’s important in a region that now faces a complex array of drug-related crimes. Twenty-five years ago the region mostly saw marijuana used and trafficked. Now, every type of drug is trafficked, and West Africa is not only a transshipment region. It is a region that produces, traffics and consumes all kinds of drugs.

There also has been an increase in connections between drug trafficking and violent extremism, Lapaque said.

“It is very important to understand that it’s not going to be easy to stabilize the world if Africa is not stable,” Lapaque said. “So that’s something which has to be clear and has to be on everyone’s radar. We cannot leave behind any weak points or regions.”