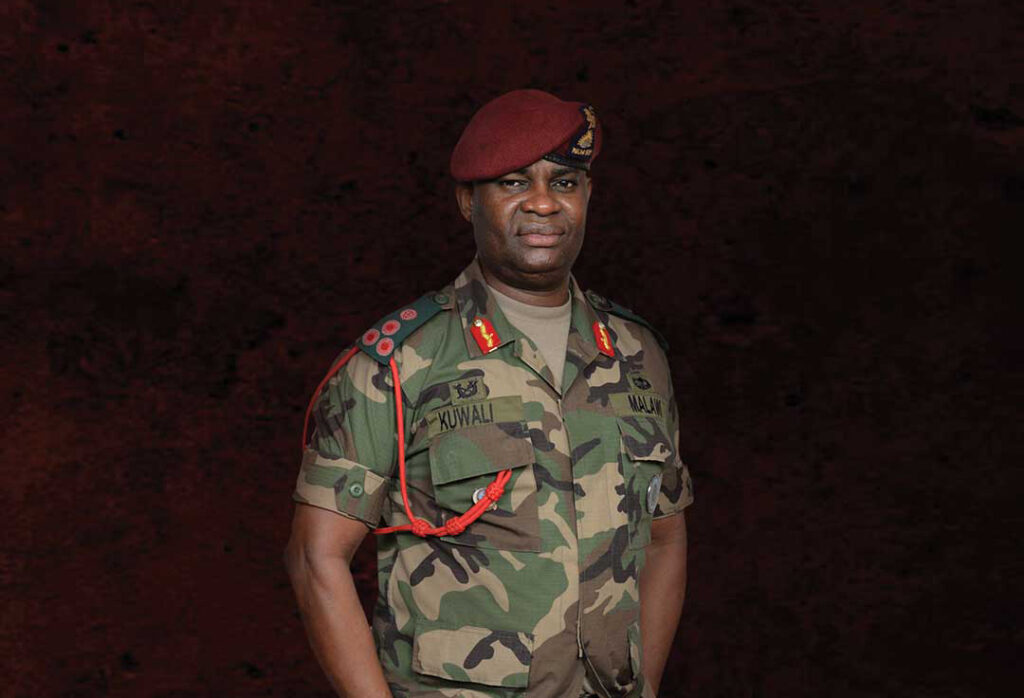

Brig. Gen. Daniel Kuwali served in the directorate of legal services for the Malawi Defence Force (MDF) for 23 years. During that time, he became chief of legal services and then was appointed the first judge advocate general of the MDF. He also has served as legal advisor in the United Nations mission in the Democratic Republic of the Congo and has taught and published widely on topics including human rights, the use of force and humanitarian law. In 2022, he graduated from the resident course as an international fellow at the U.S. Army War College and returned to Malawi, where he was appointed the nation’s first commandant of the National Defence College. This interview has been edited for space and clarity.

ADF: You graduated from law school and then joined the Malawi Defence Force. Why did you choose to join the military instead of opting for a legal career in the private sector?

Kuwali: Interesting question! Well, first and foremost was, and still is, my patriotism — the desire to serve my country. It was the fact that I would be able to direct my education, expertise and experience toward service of my country and its people. Second is the discipline, physical fitness and mental health regimens obtained in the military. They mold a person to be well rounded. Then, once you join the military, you find a huge pool of family and friends, which you tend to cherish. So, in short, my passion for service above self has been the driving factor for me to serve my country.

ADF: What is the importance of having a strong legal framework for military operations? How does it lead to disciplined and accountable armed forces? How does it help engender trust from civilians?

Kuwali: To your first question, the military should operate within the law because of the constitutional principles of rule of law and accountability. In a democracy, no person or institution is above the law. What that means is that every person can be held accountable for their acts or omission. So, everyone has to act within the law or else their conduct shall be held to be ultra vires or outside of legal bounds, and that warrants liability. Second, like in any sport such as football, any player who follows the rules of the game is regarded as disciplined and professional, thereby winning the support of the fans. For example, looking at compliance with the Law of Armed Conflict, militaries that comply with the law achieve economy of effort, avoid the commission of crimes, and earn the trust and respect of civilians, both in the mission area and at home. Eventually, these contribute to the morale of troops. The civilian population, including the legislature, is also keen to provide support to troops that do not embarrass them but instead fly the flag high.

ADF: You served as the legal advisor for the U.N. mission in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC). What types of unique challenges did you face there?

Kuwali: My tour of duty as a peacekeeper in the DRC was an eye-opener. In short, it helped me apply theory to practice. I saw that human rights violations do not come in obvious packages. They are hidden in plain sight, and it takes a discerning tact and skill to figure them out. For example, if you see an armed bandit blocking people on their way to a polling station, one may not realize that this criminal is infringing on their right to vote, freedom of movement, even threatening their right to life.

I faced challenging dilemmas as to what a military commander should do if women and children surround war criminals who are targeting peacekeepers. Is it legitimate to attack such a human shield where peacekeepers have been killed? How do you deal with a habitual offender who has been terrorizing a village and escapes from a detention center unarmed? Does a Soldier shoot to kill, to harm, or not shoot at all? These are not academic questions. Neither are they just legal questions; they have political considerations, too. As a legal advisor, you must advise in a split second. This requires one to be on top of their game.

ADF: There has been a recent upsurge in coups d’état on the continent. How do you explain this trend?

Kuwali: Military coups have occurred where troops capitalize on civic discontent to seize power from civil authorities, as was the case in Sudan in 2019. In other cases, such as Guinea in 2021, leaders seeking to cling to power flouted the electoral process and made amendments to the constitution to extend term limits. These actions increased public support for the military to seize power. While there cannot be a one-size-fits-all explanation for the proliferation of coups, the causal factors include poverty, insecurity and poor governance. Other contributing factors are endemic corruption and economic mismanagement, infrastructural deficits, poor socioeconomic systems and institutions, and frustrated youths. Africa experienced 82 coups d’état between 1960 and 2000 before the African Union was established. Between 2000 and 2022, the continent has witnessed 22 coups. This is a worrisome trend.

STAFF SGT. SEAN CARNES/U.S. AIR FORCE

ADF: Do you see any commonalities between these countries? Do you think coups are “contagious” and become more likely either regionally or continentally once one occurs?

Kuwali: Coups involve calculations of costs and benefits by plotters. The obvious benefits include power and access to state resources. The costs include the risk of death or prosecution and imprisonment. Coups d’état have a domino effect such that a successful coup significantly increases the probability of subsequent coups in that country and its neighbors. Therefore, if the putschists act with impunity, the trajectory of military takeovers will continue.

Although the AU has prohibited unconstitutional changes of governments, its response to recent coups reflects a waning resolve to enforce anti-coup norms, which is one of its foundational principles –– complete with sanctions –– against errant parties. Unless the AU demonstrates resolve in condemning unconstitutional changes of government, it will promote a regional democratic recession. The AU should enforce Article 25 of the African Charter of Democracy, Elections and Governance by consistently imposing sanctions and referring perpetrators of coups for prosecution without exception.

ADF: As a student of history, what have you seen as the short-term and long-term ramifications for a country that experiences a coup?

Kuwali: Putschists usually promise to reverse the tide and provide socioeconomic dividends to citizens. However, there is little or no evidence that coups improve governance and economic development. The opposite is true. Those who break the law in the first place cannot be expected to follow the law. Running a country requires leadership, competence and skills beyond military campaigning, strategy and tactics. Coups cannot be solutions to the inability of democracy to deliver public goods and security to the people. These stratagems are the very antithesis of a democratic culture. Therefore, coups should be condemned as a matter of principle.

ADF: What are the common factors in countries such as Malawi that have avoided nondemocratic transfers of power? Do they share any characteristics?

Kuwali: Countries that abhor coups and undemocratic transfers of power have strong oversight institutions that check executive overreach and uphold the rule of law. This is due to independent judiciaries, people-centric legislatures, vibrant media and independent electoral bodies. These countries also do not imprison human rights defenders. They establish conflict prevention mechanisms and robust security sector governance. They tend to have healthy civil-military relations and respect for democratic control of the armed forces.

It is unfortunate that the recent rise in coups has overshadowed successful transfers of power in many countries that uphold constitutionalism. This includes most countries in southern Africa, stable democracies in East Africa, especially Tanzania, and West Africa’s biggest democracies such as Ghana, Nigeria and Senegal.

ADF: From a military perspective, what can be done in terms of training, professional military education and security sector reform to reverse the trend of coups?

Kuwali: If you take a deeper dive, you will notice that most of the putschists fall outside the rank blanket of leaders who are targeted for security sector governance training. Such training is akin to preaching to the converted. It will, therefore, be prudent to cast the net wider to ensure that Soldiers — whatever their rank or responsibilities — understand and uphold the principle of civilian control of the military. On their part, civilian authorities and political leaders should increase their understanding of the security sector and facilitate periodical, meritorious promotions; transparent recruitment processes; and appropriate training to retain the trust of the armed forces.

ADF: So lower-ranking members of the armed forces don’t have enough access to strategic training?

Kuwali: The challenge in the setup of the military is that you have the strategic level, the operational level and the tactical level. That has its own challenges in the sense that issues of security sector governance are not taught at the tactical level. Troops at the operational level — and these are most of the people who have been involved in coups d’état –– do not have an idea of issues relating to security sector governance or issues relating to civilian control of the armed forces. My suggestion is that we need to start teaching issues at that level so that Soldiers grow up understanding these issues. It should become a way of life to respect civilian authorities as people who have control over the military, because these are the people who have been voted into office by citizens. It should be a way of life to respect this, because that’s what you are supposed to do in a democracy. We shouldn’t just start when leaders have risen high up in the ranks. They say you can’t teach an old dog new tricks, so the earlier we start, the better. In that case, we will have a critical mass of people who understand democratic principles.

ADF: What are your short-term goals for leading the soon-to-be-established Malawi National Defence College (NDC)?

Kuwali: My short-term goal is to come up with a solid, comprehensive syllabus that will look at the needs of the Malawi Defence Force and Malawi as a nation, as well as looking at how the MDF, along with allies, can counter contemporary threats. Number two, we have to have the college established. We’ve identified a place but are waiting for government procedures. Once we do that, I will have to come up with a team who will be teaching the courses.

ADF: What are your long-term goals?

Kuwali: My long-term goal is to have as many course participants as possible who can go through the corridors of the NDC in Malawi and to also have the institution as a center of excellence. It should be an institution of choice for leaders, not just in Malawi, but across the continent. We also want to have our own niche. We should develop indigenous warfighting strategies to see how best we can improve them. We cannot just be adopting strategies that have worked elsewhere.

We need to dig deep into the military history of African countries, because too often we’re just looking at world wars to draw lessons. We need to look at our own wars to see what triggered them and how they ended. In so doing we will find our own indigenous or traditional ways of resolving conflicts. Apart from that we want to develop conflict prevention mechanisms. Neighboring states should not be looking at each other as threats; they need to be looking at each other as neighbors. We need to come up with exercises for conflict resolution as part of our strategy of confidence building on the African continent.