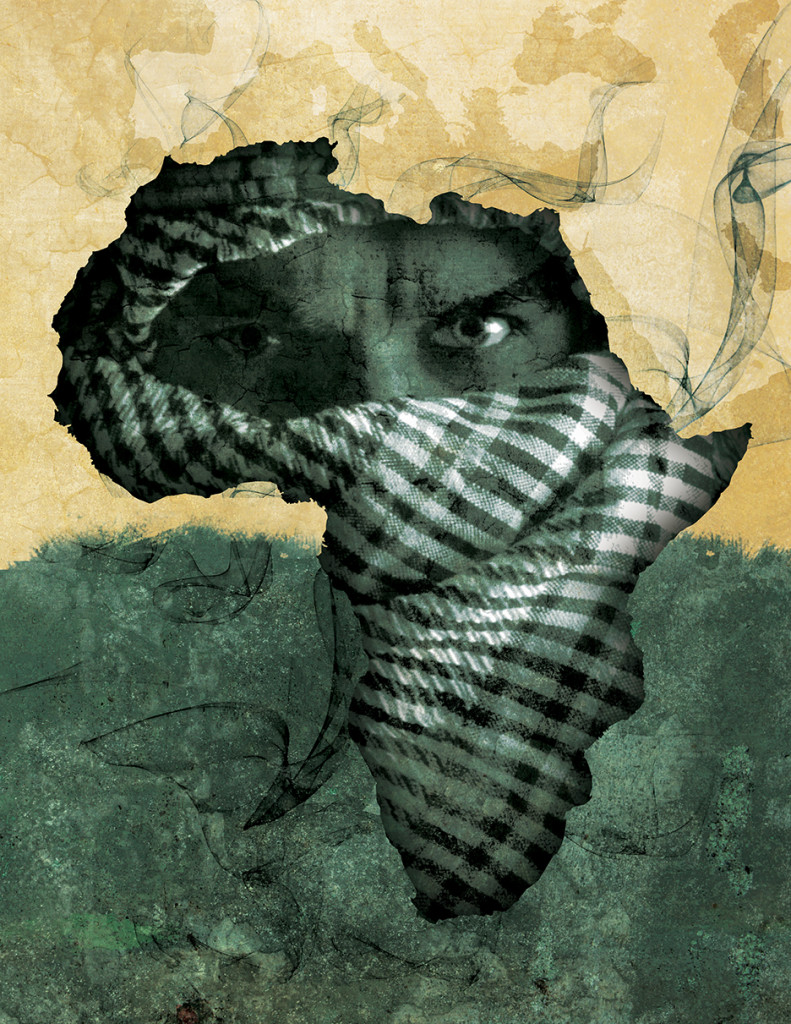

In North Africa, extremists who fought alongside ISIS on the battlefield are returning home.

At the beginning of 2015, an estimated 31,000 fighters in the self-proclaimed Islamic State of Iraq and Syria, or ISIS, had tightened their grip over a vast swath of land. Thousands of those fighters were African. And as ISIS tries to expand into new territory, African fighters have begun to return to their home countries. They are bringing their extremism with them.

ISIS, also known as ISIL, began in 1999 in Iraq, founded by the now-deceased Abu Musab al-Zarqawi, a militant Islamist from Jordan. In 2004, the group pledged allegiance to al-Qaida. Its current iteration began in 2010, when Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi assumed command. In February 2014, al-Qaida cut ties with the group due to disputes over doctrine and tactics.

Al-Qaida reportedly was particularly troubled by ISIS’ interpretation of takfir, which is when a Muslim declares another Muslim to be a heretic. ISIS has used this as justification for killing other Muslims in regions it controls.

The two groups have slightly different philosophies. Al-Qaida sees itself as a band of avengers, trying to spread its agenda through violence. ISIS has used equally violent tactics but is also more interested in governance, trying to establish ISIS-administered regions and cities.

Life in areas controlled by ISIS is brutal. ISIS forbids alcohol, tobacco, secular music and the rights of women. Muslims and non-Muslims alike have been routinely murdered, crucified, beaten and whipped. In early 2015, ISIS soldiers put a Jordanian pilot in a cage and burned him alive. At its core, ISIS, like Nigeria’s Boko Haram, appears to reject all things Western.

Under al-Baghdadi’s leadership, ISIS has become indisputably the wealthiest terrorist group in the world. South African journalist Simon Allison, in a policy brief for the Institute for Security Studies, said that ISIS gets its wealth from oil fields, looted banks and tax collections in the regions it controls. At one point in 2014, ISIS assets were confirmed at $2 billion.

The Guardian reported that ISIS also has made money by smuggling raw materials pillaged in Syria as well as priceless antiquities from archaeological sites. In one instance, ISIS made $36 million on antiquities taken from a single dig site. Some of them were up to 8,000 years old.

WORLD AMBITIONS

The group’s ambition knows no limits. On June 29, 2014, ISIS proclaimed itself a worldwide caliphate with al-Baghdadi as its leader. ISIS says it is now the final authority on Islam and claims absolute authority over all Muslims worldwide.

To accomplish this, al-Baghdadi’s extremists use the modern tools of propaganda, including videos and social media. They represent a sharp departure from the long online sermons of al-Qaida leaders.

“Videos put forward by the ISIS tend to be filled with rank-and-file members whom potential recruits find much more relatable than al-Qaida’s videos full of leadership figures giving speeches,” said a December 2014 report from the Combating Terrorism Center at West Point. “This ‘relatability,’ paired with slick production techniques and military successes on the ground, appeals to a new generation of recruits for the ISIS.”

Shiraz Maher, a senior fellow at Kings College London, said ISIS has moved beyond the traditional password-protected websites extremists have used in the past.

“Web forums are less important these days, giving way to platforms such as Twitter, Facebook and Instagram,” Maher wrote in The Guardian. “In this respect, ISIS has harnessed the power of these platforms better than any other jihadist movement today. Online, it has created a brand, spread a seductive narrative, and employed powerful iconography. This strategy has been responsible for inspiring thousands of men from all over the world to join the group.”

With al-Shabaab, Boko Haram, al-Qaida in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM) and other extremist groups already established in Africa, parts of the continent are already primed for ISIS to spread its ideology. If ISIS does advance on the continent, it will almost assuredly be with the cooperation of some of these groups. In fact, some have already pledged their support.

Of particular concern are the parts of Africa that are lacking in government services, such as northeast Nigeria, where the police and military have been unable to curtail the operations of Boko Haram. Somalia, with its recent history of al-Shabaab occupation, also could be a possible target for ISIS. Egypt and Libya already have ISIS strongholds.

Allison said the biggest danger for African countries — particularly Algeria, Libya, Morocco and Tunisia — is the “potential impact of thousands of well-trained, battle-hardened fighters choosing to return, or being ordered home after stints with [ISIS] or other jihadist groups in Syria.”

ISIS IN AFRICA

These are some of the African nations dealing with ISIS fighters:

ALGERIA: In September 2014, the Soldiers of the Caliphate, also known as Jund al-Khilafa, pledged their allegiance to ISIS. The group, an offshoot of AQIM, accused it of deviating from the “true path.” Members vowed absolute obedience to ISIS, and two weeks later they beheaded a French citizen in retaliation for France participating in airstrikes on ISIS in Iraq.

Terrorism Research & Analysis Consortium Editorial Director Veryan Khan told New York magazine that the beheading was particularly significant in that it was done “on the Islamic State’s behalf.”

EGYPT: ISIS set up operations in Egypt’s northern Sinai Peninsula in mid-2014, attacking Egyptian Soldiers, police officers and civilians. An ISIS video indicated that the group had set up military checkpoints in Egypt near the Mediterranean, along a main road linking Al-Arish with the Palestinian city of Rajah. In the video, ISIS said it would attack Egyptian Soldiers and “spies for the Jews.” In mid-December 2014, ISIS released a video showing it killing three Egyptian Soldiers in a drive-by shooting.

The Egyptian faction of ISIS calls itself Wilayat Sinai (Sinai Province). The New York Times said the faction is composed mainly of an existing group called Ansar Beit al-Maqdis, which has about 1,000 militants. The group, formed during the Egyptian revolution in 2011, was regarded as the most dangerous extremist organization in Egypt. It pledged allegiance to ISIS in November 2014, hoping for resources and weapons to overthrow the leadership-in-turmoil in Cairo.

Before aligning with ISIS, the group was already a significant force. Voice of America reported that the group had “grown increasingly proficient in carrying out attacks” and had become more sophisticated in selecting targets based on their strategic value. It stepped up its attacks after the July 2013 ouster of President Mohamed Morsi by the Egyptian military. Early attacks were confined to the Sinai Peninsula, but it has expanded its range of operations to include Cairo.

In January 2015, Egyptian officials arrested nine men who were trying to enter Egypt from Libya. The Kuwaiti newspaper Al-Rai reported that the men were on a mission to kill government ministers, media personalities and businessmen. The nine were from Pakistan, Afghanistan and Egypt.

LIBYA: The country has been unstable since the overthrow of Moammar Gadhafi in 2011. Vast numbers of the weapons stockpiled throughout the country have since been pillaged and sold on the black market. Libya itself has become a training ground for extremist fighters.

A new group calling itself the Islamic Youth Shura Council took over the coastal Libyan city of Derna in April 2014. The group initially allied itself with al-Qaida but switched its allegiance to ISIS in June 2014. In a statement, the group said, “It is incumbent on us to support this oppressed Islamic State that is taken as an enemy by those near and those far, among the infidels or the hypocrites, or those with dead souls alike.”

Although the group’s absolute control of an entire city of more than 80,000 is disturbing, it should not come as a complete surprise. CNN International reported that the city contributed 800 fighters to the ISIS invasion of Iraq. The network also reported that the city was home to a large number of fighters in the Syrian civil war. Those returning fighters led the siege of the city, The Washington Times reported. The group took control of government buildings, security vehicles and local landmarks. They were using a football stadium for public executions.

“ISIS pose a serious threat in Libya,” former Libyan extremist Noman Benotman told CNN. “They are well on the way to creating an Islamic emirate in eastern Libya. Most of the local population in Derna are opposed to the takeover by the Islamic State, but, with the complete absence of any central government presence, they are not in a position to do much for now.”

One of the group’s most brutal and high-profile atrocities took place in Libya in February 2015 when ISIS militants beheaded 21 Egyptian Coptic Christians. ISIS released a video of the killings, which the Egyptian government and the Coptic Church confirmed as authentic.

MOROCCO: In January 2015, Morocco announced that it had dismantled an Islamist militant cell sending fighters to Syria and Iraq to join ISIS. Reuters reported that the fighters were under instructions to attack their homeland when they returned.

The cell had been active in the city of Meknes and the towns of El-Hajeb and El-Hoceima in the Northern Rif mountains, Moroccan officials said. One official said the government thinks that nearly 2,000 Moroccans have fought alongside ISIS in Syria and Iraq.

Social media videos of armed Moroccan ISIS fighters vowing to overthrow the Moroccan government have been circulating in the country.

NIGERIA: Although there have been no reports of ISIS movements in Nigeria, observers have seen its influence in the tactics and rhetoric of Boko Haram rebels in the northeast.

“There are no direct operational contacts,” said J. Peter Pham, head of the Africa Center at the Atlantic Council, in December 2014. “But it is quite clear that Boko Haram is paying attention to [ISIS,] and [ISIS] is paying attention to Boko Haram.”

In March, Boko Haram formally pledged allegiance to ISIS and al-Baghdadi endorsed the alliance calling Boko Haram “our jihadi brothers.”

African specialist Jacob Zeen of the Jamestown Foundation told Agence France-Presse that Boko Haram initially had received backing from AQIM, but, “It has more recently begun to model its ideological and military doctrine after the Islamic State and, in turn, has started to receive recognition from the Islamic State.”

Pham said Boko Haram has begun promoting itself in the same way ISIS has.

“They use heavy equipment, they parade with tanks taken from the Nigerian army flying the black flag, like they saw on ISIS videos,” he said. “ISIS presents a compelling model. Al-Qaida is the brand of yesterday.”

ISIS, in turn, has been influenced by Boko Haram. When ISIS took Yazidi hostages in Iraq in 2014, it cited Boko Haram’s infamous kidnapping of 276 girls in Chibok, Nigeria. As of early 2015, Boko Haram was adopting another ISIS tactic — in addition to its raids, it was beginning to hold territory.

TUNISIA: Tunisia, a secular country, is widely viewed as a model for democratic reform after the Arab Spring revolutions. But that could be changing. The Guardian estimated that there have been more Tunisians among foreign extremists fighting in Syria and Iraq than from any other country.

Tunisia estimates that at least 2,400 of its citizens have become combatants in Syria since 2011, and that as of early 2015, about 400 have returned. “In Douar Hicher, a poor district at the edge of Tunis, it is common knowledge that 40 or 50 young men have left to fight and perhaps a dozen have been killed,” the newspaper reported.

Two Tunisian militants who murdered secular politicians in 2013 said in December 2014 that they had since joined ISIS. “We are going to come back and kill several of you,” one of the militants said in a video. “You will not have a quiet life until Tunisia implements Islamic law.”

KEEPING THE RULE OF LAW

ISIS hopes to plant its flag in Africa. Aaron Y. Zelin, writing for The Washington Institute, said that the ISIS-based occupation of Derna could be a model for “future acquisition of territory by the Islamic State beyond its base in Iraq and Syria.”

“This model would also diverge sharply from how al-Qaida had done business in the past, namely, relying primarily on autonomous local franchise organizations,” he wrote.

In confronting ISIS, experts agree on one point: Military intervention will undoubtedly be necessary, but a heavy hand won’t work. The Institute for Security Studies said its research indicates that stopping any extremist groups requires adherence to the rule of law and a criminal justice-based approach within a country’s own legal framework. Other organizations concur.

“Too often, in the name of counterterrorism, security forces forget that human rights violations such as detainee abuse, denial of fair trial guarantees, extrajudicial killings and unlawful renditions create instability by undermining the rule of law and alienating affected populations,” the New York-based Open Society Justice Initiative wrote. Such tactics, the initiative said, “do little to reduce terrorism violence,” and “may well make the situation worse.”

ISIS Leader Shrouded in Secrecy

Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi is the undisputed leader of ISIS. But beyond that, remarkably little is known about him.

He claims to be a direct descendant of the prophet Muhammad. For the most part, he is a mystery. Even the elements of his childhood are widely disputed.

He does not allow photographs or videos of him. He maintains a low profile and is said to wear a mask when meeting with prisoners.

Al-Baghdadi joined a small armed group in eastern Iraq after the American invasion. In 2005, he was captured and sent to Bucca prison camp in southern Iraq. There, he is believed to have met and trained with al-Qaida fighters. Over the course of his time in prison, he consolidated his power.

In 2010, after the deaths of two of the leaders of al-Qaida in Iraq, al-Baghdadi took charge. At that time, the Sunni rebellion was foundering. The civil war in Syria changed everything. The sudden lack of authority in large areas of Syria opened the door for the growth there of al-Qaida.

In June 2013, he rejected al-Qaida and its leader, Ayman al-Zawahiri.

“ISIS’ rise at the expense of Zawahiri’s movement signals that a new, more dangerous hybrid based on state development by wrecking everything in its path is emerging from the Syrian terrorist incubator,” wrote Theodore Karasik of the Institute for Near East and Gulf Military Analysis. “Ultimately, ISIS seeks to create an Islamic state from where they would launch a global holy war. Perhaps that war is now beginning as Baghdadi’s ISIS eclipses Zawahiri’s al-Qaida.”

Al-Zawahiri, some observers said, is now seen as ineffective, compared to his ISIS rival.

“For the last 10 years or more, [al-Zawahiri] has been holed up in the Afghanistan-Pakistan border area and hasn’t really done very much more than issue a few statements and videos,” Richard Barrett, a former counterterrorism chief at Britain’s foreign intelligence service, told Agence France-Presse. “Whereas Baghdadi has done an amazing amount — he has captured cities, he has mobilized huge amounts of people, he is killing ruthlessly throughout Iraq and Syria.”