6 Major Human Security Threats Are Connected to Each Other

ADF STAFF

Security threats are not always measured in guns, bullets and armed conflicts. Sometimes, the things that most threaten communities — and nations — are rooted in the environment or in the day-to-day interactions of people and the land around them.

Many human security threats are seemingly disparate and random. But a closer look indicates that most of them are interrelated. If one worsens or intensifies, it can exacerbate the effects of others. The results can be as wide-ranging and catastrophic as war or civil unrest.

When looking at climate change, food security, population growth, clean drinking water, energy security and wildlife poaching, the links become clear.

Climate change can lead to droughts. Prolonged dry spells can dry up fish-rich lakes and reduce crop yields. This can lead to a lack of food security in nations or entire regions as nutrition sources are reduced.

Concurrent with these developments are projections that Africa’s population will double, and eventually quadruple, by the end of the century. When a region can no longer support a population, people often migrate, affecting food security in new areas.

As populations grow, so will the need for clean drinking water. Water demands, especially between farming and pastoralist communities, often lead to unrest and violence. With climate change, precipitation can decrease, endangering crops, food security and water availability.

Population growth also will increase the demand for electricity and energy security. Many African nations will strain to provide the infrastructure needed to generate and transmit reliable power to growing populations.

Finally, wildlife poaching may not appear to be connected to other human security issues, but climate change clearly increases the risk to endangered animals. Fluctuating precipitation levels can produce floods and droughts, forcing animals to venture out from preserves or their natural habitats in search of food or water. This can make them more vulnerable to poachers. The resulting slaughter, which at times approaches an industrial scale, is a drain on tourism.

Here is a statistical look at the six human security threats.

Africa is the second-driest continent on Earth. As the population continues to grow and global temperatures rise, the availability of clean drinking water, as well as water for agriculture, will be a top concern.

There are many challenges. Only 15 percent of Africa’s renewable water resources are groundwater, but nearly 75 percent of the population depends on this for drinking water, according to the United Nations Environment Programme’s Africa Water Atlas. Many African aquifers, such as the Nubian Sandstone, are losing water faster than they can be recharged.

Many African countries struggle with providing improved water sources. In 2015, less than three-quarters of the populations in Equatorial Guinea, Eritrea, Mauritania, South Sudan and Sudan had access to an improved drinking water source, according to the World Bank. Such improved sources include piped water to homes, plots or yards; public taps and standpipes; tube wells and boreholes; protected dug wells; rainwater collection; and protected springs.

Sixty-three percent of Africans have access to piped water. About 93 percent have access to cellphone service, according to surveys conducted in 35 countries.

Source: Afrobarometer

Africa’s vast, expansive landscape includes at least eight climate zones, including tropical rain forest, desert, subtropical, savannah, highland and marine. Rainfall can range from 5 centimeters a year in the desert to 4 meters in rain forests.

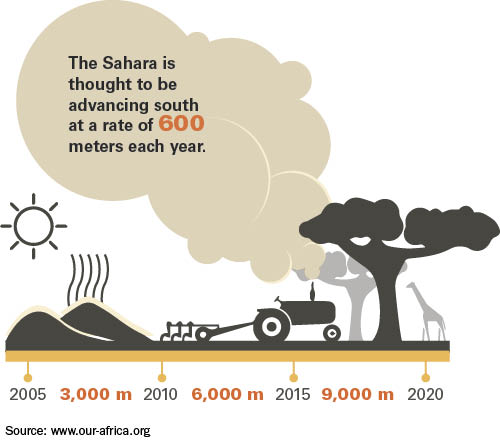

Weather patterns are changing across the continent. Droughts are becoming more common across the Sahel, and as temperatures climb, the Sahara expands southward. This desertification is most prevalent in areas where people have cleared trees and forests for farmland or to get wood for fires.

The severity of climate change’s effect on African poverty levels will be determined in large part by political and economic policies regarding jobs, technology and development, according to a 2016 World Bank Group study.

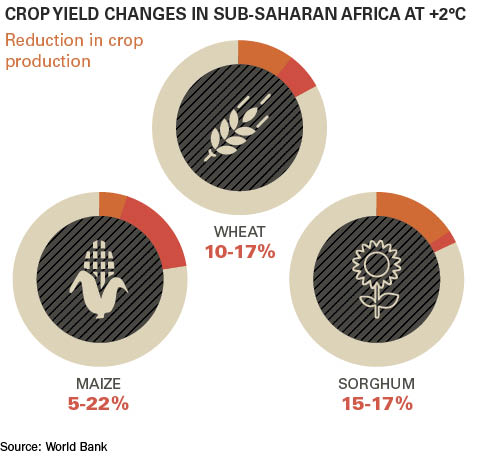

Food security can be affected by a host of human security issues. Climate change and weather variations, such as

El Niño, can strain agricultural yields and throw regional food supplies and costs into a crisis.

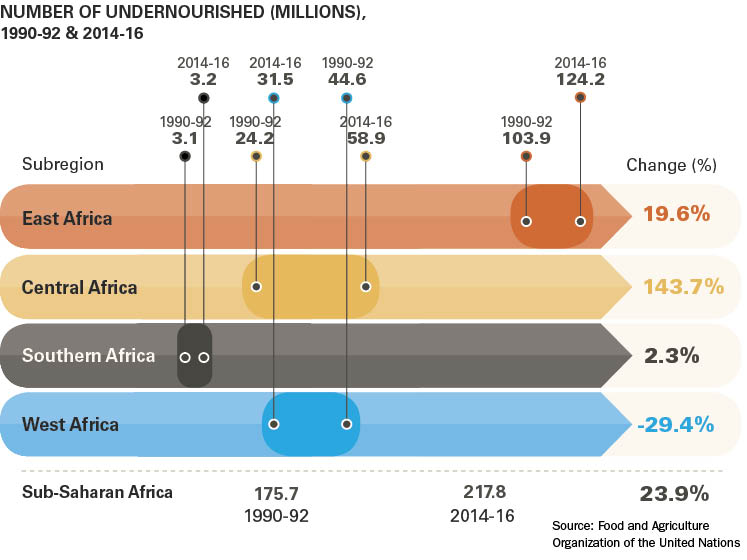

Climate magnifies already-systemic hunger and poverty: 1 in 4 people in Sub-Saharan Africa is undernourished.

Africa also has its share of conflict. This unrest contributes to poverty and hunger. “Poverty rates are 20 percentage points higher in countries affected by repeated cycles of violence over the last three decades,” according to a 2011 World Bank report. “People living in countries currently affected by violence are twice as likely to be undernourished and 50 percent more likely to be impoverished.”

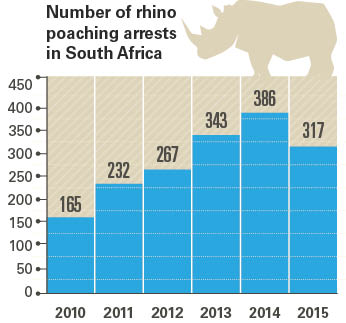

Elephants, rhinos and other exotic animals are falling to poachers at an alarming rate in Africa. Ivory and rhino horn bring huge sums of money in black-market sales, particularly in Asian countries such as China and Vietnam.

With this illegal trade comes the endangerment of some of Africa’s most treasured animals, which bring in significant money through national tourism.

With this illegal trade comes the endangerment of some of Africa’s most treasured animals, which bring in significant money through national tourism.

It’s not just elephants and rhinos that are poached in Africa. Several varieties of birds, including ducks and parrots; butterflies; pangolins; monkeys and chimpanzees; and even sharks are targeted.

The losses are staggering. According to an August 2015 report in National Geographic, Zakouma National Park in Chad has lost nearly 90 percent of its elephants since 2002 — as many as 3,000 between 2005 and 2008. In 2012, Sudanese and Chadian poachers rode horses into Cameroon’s Bouba N’Djida National Park, where they killed up to 650 elephants in four months.

The World Wildlife Fund reports that poaching is the fifth-most lucrative of the world’s illicit trades, bringing in up to

$10 billion a year.

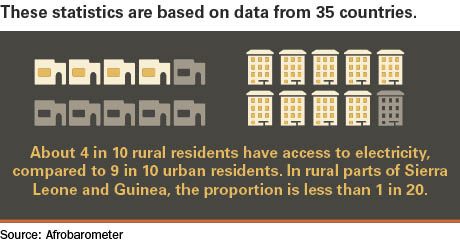

A sure sign of effective development is the percentage of people who have access to electricity. Africa has tremendous potential in this area, but much work remains. Energy demand in Sub-Saharan Africa grew by about 45 percent from 2000 to 2012, but more than 620 million people there still have no access to electricity, according to a 2014 International Energy Agency (IEA) report.

In fact, as of 2012, less than 10 percent of the populations of five African countries had access to electricity: Burundi, Chad, Liberia, Malawi and South Sudan, the World Bank reported.

But there is reason to be hopeful: By 2040, 950 million people in Sub-Saharan Africa are expected to get access to electricity. Urban residents will be connected to the grid, and rural populations will gain access through off-grid solutions and renewables, which are encouraging private investment, the IEA says.

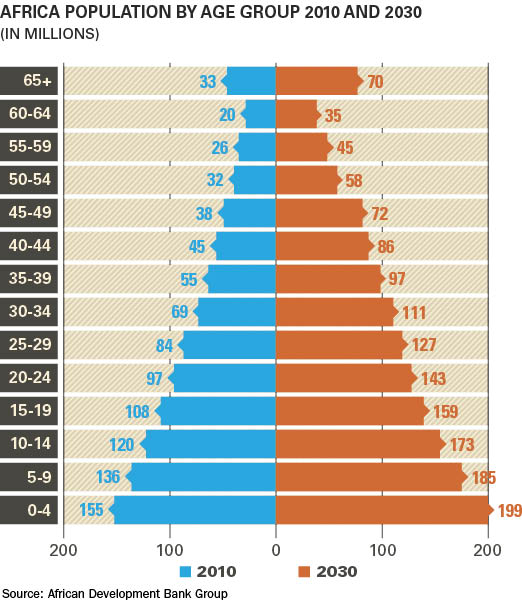

Africa is the world’s second-most populous continent, behind Asia. But it is poised to grow at an amazing rate between now and the end of the century.

The populations of 28 African countries — more than half the countries on the continent — are expected to more than double between 2015 and 2050, according to the United Nations’ “World Population Prospects, 2015 Revision.” By 2100, 10 African countries are expected to see their populations increase by at least five times: Angola, Burundi, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Malawi, Mali, Niger, Somalia, Tanzania, Uganda and Zambia.

Population changes are likely to be at the center of various human security challenges. Migrations will occur in areas of conflict and where climate change is most severe. More dense populations can intensify the spread of disease and strain water resources. Finally, if population growth is not matched by economic growth, unemployed young people can become frustrated. This leaves them more vulnerable to recruitment by extremist groups or could push them to risk their lives as migrants.