Chad’s intervention in northern Mali offers lessons in resolve and sacrifice

ADF STAFF

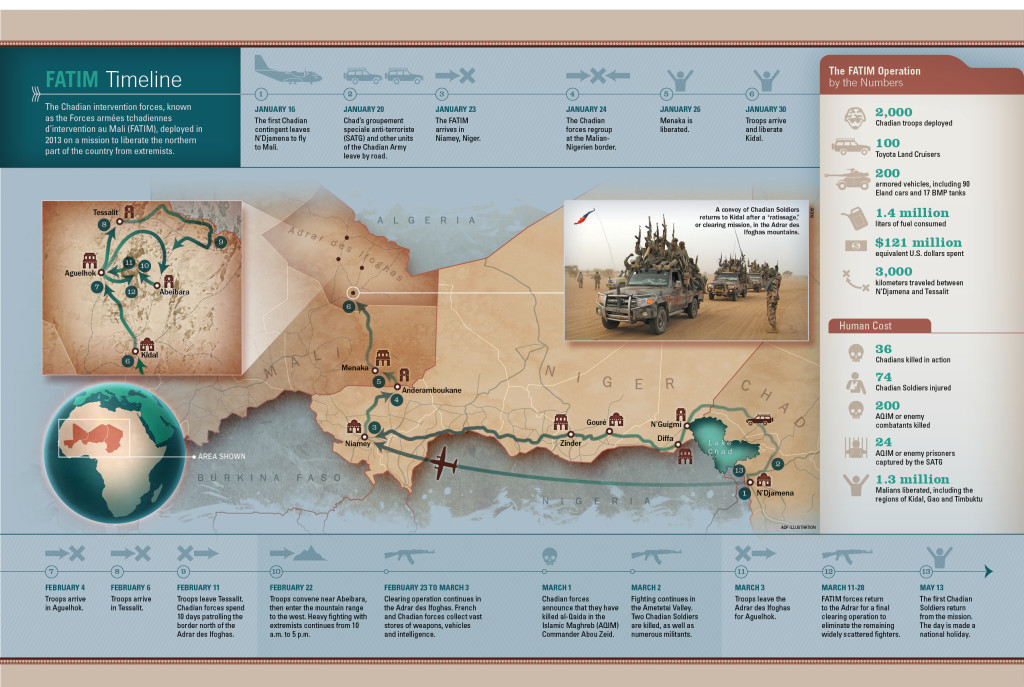

A column of about 100 Chadian light vehicles, mostly Toyota Land Cruisers, left Chad’s capital, N’Djamena on January 20, 2013. The convoy curled around the Lake Chad basin before reaching the border with Niger. Days earlier, nearly 200 armored vehicles, including 90 Eland armored cars and 17 BMP tanks, were airlifted to Niger’s capital, Niamey.

At the Niger border-crossing, Brig. Gen. Abdraman Youssouf Mery, commander of Chad’s elite groupement speciale anti-terroriste (SATG), halted the convoy and gathered his officers around him.

![Gen. Oumar Bikimo, seated right, discusses strategy with officers outside Menaka in eastern Mali as they prepare to move north toward Kidal. [FATIM]](https://adf-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/CarpetTalk.jpg)

“We are going outside of our borders now,” he recalled instructing the men. “We are going to help the population, our fellow Africans, so we have to respect the laws and the rules of these foreign countries and respect human rights. Remember, we are going there to bring peace to our neighbors.”

The mission was an ambitious one. Four days earlier, the Chadian National Assembly had voted unanimously to endorse military action in Mali. Although Chad has modest means and shares no borders with Mali, the country reached into its own pocket and paid $121 million to send 2,000 of its Soldiers to join the fight.

It was, according to President Idriss Déby Itno, a “just cause” and a “duty” for Chad.

“Africans need to understand that they have a role to play when it comes to stability and peace on the continent,” Déby said on January 16, 2013. “It is time for Africans to put themselves at center stage.”

There was little time to waste. Groups aligned with al-Qaida had captured more than two-thirds of Mali. Pushing south, they took the strategically important town of Konna and appeared headed for the capital, Bamako.

In an act of supreme arrogance, Abdelmalek Droukdel, emir of al-Qaida in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM), issued a 10-page manifesto to his fighters outlining what an al-Qaida-governed state would look like for decades to come. Islamist fighters began meting out harsh justice in many cities they governed, including public whippings. More than 250,000 Malian civilians fled the country.

Desert Foxes

Mery’s convoy pushed on, covering more than 1,500 kilometers in three days despite stopping often to greet local dignitaries at Nigerien villages. Chadians are known for their ability to cross vast spaces in a short time. This is a necessity in a nation measuring nearly 1.3 million square kilometers, with widely dispersed population centers. In wars against Libya in the 1980s, the Chadian Army also became known for a dazzling attack style that allowed them to surprise and outmaneuver the well-armed Libyans. The French called it “rezzou TGV” in reference to the ancient raiding tactics used by Saharan nomads called razzia and TGV, a French acronym for a lightning-fast train.

“They are intrepid, efficient and with their own aesthetic (turbans and sunglasses),” wrote researcher Géraud Magrin. “They lead attacks with a column of Toyotas equipped militarily and sent at top speeds.”

The Chadians knew they were uniquely qualified for the fight in Mali’s mountains. The salient feature of northern Chad is the volcanic Tibesti mountain range, one of the world’s most desolate places and a magnet for terrorists and traffickers. In 2004, when the extremist Salafist Group for Preaching and Combat set up in the Tibesti Mountains, it was the Chadian Army that drove them out and arrested a top commander.

![[FATIM]](https://adf-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/Sunset.jpg)

“Mali is almost like Chad — it’s nearly the same environment,” said Gen. Mahamat Déby Itno, the son of Chad’s president and the second in command of the Chadian forces in Mali. “We have the Tibesti [Mountains] in Chad — the Soldiers are hardened to it. They’re trained for any terrain — the desert, the mountains, the forest. It doesn’t make a big difference to us.”

3,000-kilometer journey

By January 25, the Chadian intervention forces, known as the Forces armées tchadiennes d’intervention au Mali (FATIM), crossed the Malian border and headed toward Menaka, a town of squat mud-brick houses about 100 kilometers from the border.

The giant convoy advanced slowly, with contingents separated at intervals of 5 to 6 kilometers. “We sent scouts out ahead and divided into three columns,” Mery said. “Our thought was that at any time we were driving, the terrorists could come out. We didn’t want to take any risks.”

At dusk they reached Menaka and encircled the village to block all entry and exit points. The next morning, the Chadian officers went in to meet the village elders. They found that the previous occupiers, the extremist group the Movement for Oneness and Jihad in West Africa (MUJAO), had fled but left behind evidence of a three-month reign. There were black flags hanging from walls and crude paintings of swords on the village gates. Schools and market stalls were locked shut.

At the sight of the incoming Soldiers, excited children climbed onto roofs cheering and began ripping up the black flags. “They cried out for liberty,” said Gen. Oumar Bikimo, the commander of FATIM who had more than 30 years of experience under his belt and had commanded a multinational peacekeeping force in the Central African Republic. “It was, for them, a renaissance, if you will.”

![Chadian Soldiers operate in the Valley of Ametetai in northern Mali as part of the Chadian effort to liberate the region. [FATIM]](https://adf-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/WoahSand.jpg)

A delegation of village elders gathered under a patch of acacia trees and offered a herd of goats to feed the visiting Soldiers. Under the hardship conditions, the gift was worth more than 1 million Central African francs. “They said, ‘We will have a feast,’ ” Mery said. “I said, ‘No, we are too numerous, and we have our own food. We are here to help you, not you for us.’ ”

Villagers recounted that under MUJAO control they were not able to smoke cigarettes, chew tobacco or even eat kola nuts. The small community radio station, Radio Aadar, had been forced to cease playing music and switch to sermons. Men were made to grow their beards, and women caught speaking to a man in public risked being whipped.

“Right now, we’re trying to re-establish the social life,” a village elder said. “The population was really traumatized. They were also restricted of certain rights. Today you can see the rights have returned. If you listen to the radio, if you see the youngsters walking in the street with their mobile phones, that tells you that liberty has returned.”

The reception told the Chadian forces that their enemy had made a tactical retreat. Mery, Bikimo, Mahamat Déby and the rest of the Chadian commanders knew that they had to push farther north where fighters would be waiting for them.

The next day, the FATIM forces set off toward rebel strongholds in the mountainous region bordering Algeria, a distance of 3,000 kilometers from their starting point. There was no direct road leading from Menaka to Kidal, the regional capital in northeast Mali, so the convoy traveled over sand and through brush despite the danger of ambush. GPS coverage was spotty in the area, and the heavily laden trucks, typically hauling 250-liter barrels of water or fuel, food, bedding, weapons and up to 10 men, sometimes became stuck in the sand.

Mery and other leaders stayed in regular communication with the Chadian Operations Center in N’Djamena, which passed on the latest intelligence. At the same time, French forces operating under the name Operation Serval were conducting bombing raids on terrorist targets near the Malian cities of Mopti, Konna and Gao, and were coordinating their activity with the Chadians.

Mery and other leaders stayed in regular communication with the Chadian Operations Center in N’Djamena, which passed on the latest intelligence. At the same time, French forces operating under the name Operation Serval were conducting bombing raids on terrorist targets near the Malian cities of Mopti, Konna and Gao, and were coordinating their activity with the Chadians.

“We didn’t know the region, and we didn’t have a local representative with us; we were alone,” Mery said. “We had a team of about 15 French liaison officers with us. They communicated with the [Operation] Serval, and they helped logistically. Particularly if there were injured or sick Soldiers, they arranged to airlift them.”

The Chadian forces arrived in Kidal in the afternoon of January 30. On the previous night, the French forces had landed at the airport with fighter jets and helicopters. Two Chadian contingents encircled the city and occupied entry points and the deserted military barracks. A third contingent entered the city.

On the first day, many in Kidal stayed shuttered inside their homes out of fear. In this dusty trading outpost with a population of 25,000, perhaps only one-third of the residents had remained. A visiting film crew termed it a “village of phantoms.” Days of bombing by the French Air Force to take out logistic depots and training camps in the area had also jangled the nerves of the local populace.

The FATIM forces immediately sensed the situation was different than in Menaka. Kidal had been a bastion of resistance for the Mouvement National de libération de l’Azawad (MNLA), the Tuareg-led independent movement. For months, there had been an uneasy alliance between the MNLA and various extremist groups, including Ansar al-Dine (Defenders of the Faith), whose notorious founder Iyad Ag Gali is a Kidal native. The MNLA eventually kicked out the extremist groups, but they refused to let any members of the Malian Army enter the town.

“We were welcomed, but the difference in Kidal was the close presence of terrorists,” Bikimo said. “You have to understand, their base was not far from there. Later, [in Kidal] we would be hit with a suicide attack in the middle of the market. We lost four of our men, and more were injured. That’s why I say there was a difference.”

Evidence of the recent struggles was everywhere in Kidal. Angry graffiti spray-painted on the walls denounced both the government of Mali and AQIM. The separatist flag of the Azawad flew outside some homes and shops. Many in town also feared reprisals and interethnic fighting, so part of Chad’s responsibility was to conduct patrols to prevent bloodshed between civilians. The French and Chadians brokered an agreement with the MNLA to work together to secure the region.

![A Chadian armored vehicle is destroyed after hitting a land mine in northern Mali. The occupants of the vehicle were injured in the blast but survived. [FATIM]](https://adf-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/Blinde.jpg)

In quick succession on February 4 and 6, the Chadian and French forces moved north to liberate Aguelhok and Tessalit, two cities that sit at the base of the Adrar des Ifoghas. In Tessalit, the FATIM forces waited for days while the French airlifted heavy equipment, such as tanks and Caesar 155-millimeter truck-mounted artillery systems.

Into the Adrar

On February 11, FATIM forces received the green light to advance toward the extremists’ mountain hideout. For 10 days, the Chadian units made a tour of the outside of the Adrar des Ifoghas mountains, traveling along the Algerian border. Methodically, they sealed off the northern perimeter to ensure that fighters could not flee across to Algeria. Another FATIM contingent left Aguelhok driving along the northern side of the Adrar, and the two contingents met near the tiny town of Abeibara northeast of the mountain chain. They were drawing a noose around the AQIM sanctuary. “We wanted to see — are there people who are crossing over? Who is entering, who is leaving?” Mery said.

On the morning of February 22, the Chadian forces assembled at the eastern edge of the mountain range. French forces had given them the GPS coordinates of certain spots where the terrorists were likely to be hiding, including wells or water sources, but the Chadians knew the fight was not going to be easy. Aerial bombings had little impact here, and the complex network of AQIM caves, tunnels and sheltered hideouts could only be found on foot. Locals told FATIM Soldiers that the central government had been absent from the region for at least 10 years.

The convoy of hundreds of Chadian forces advanced through the single entry point to the east of the Adrar, a dry riverbed called the Tigharghar Wadi. They traveled about 30 kilometers inside before reaching the AQIM logistical base, where fighters seemed to have been expecting an attack from the western front, but were prepared to fight the Chadians coming from the east.

“I think they were waiting for our arrival,” Bikimo said. “You cannot say that they weren’t prepared, because they were already positioned. Well, that tells you that they were waiting for something.”

The fighting lasted from about 10 a.m. to 5 p.m. It was a battle at close quarters, with AQIM extremists spraying rounds with Kalashnikovs and blasting rocket-propelled grenades. When the fighters were cornered, they would retreat inside cave-like dwellings, only to detonate themselves rather than surrender. “They carved out individual positions where you can’t imagine there would be a position,” Bikimo said. “They used all tools at their disposal.”

![Vehicles like this one were rigged to explode and scattered throughout the Adrar des Ifoghas. [FATIM]](https://adf-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/Van.jpg)

The Chadians, initially taken by surprise, redoubled their efforts. Climbing rock mounds to take high positions and fighting meter by meter and “rock by rock,” they eventually turned the tide.

“Sincerely, they were not prepared to give themselves up,” Bikimo said of the enemy. “We took some captive, despite their efforts, but otherwise they would have killed themselves. All the leaders refused to give themselves up.”

The costs were heavy. Among the dead was the commander of the Chadian Special Forces, Abdel Aziz Hassane Adam, a veteran who had led peacekeeping missions in Burundi, Côte d’Ivoire and the Democratic Republic of the Congo. In total, 26 Chadian Soldiers died as a result of the battle, with 53 more injured. On the opponents’ side, the deaths totaled nearly 100.

The fruits of the operation were plentiful, however. The Chadians captured a radio and, from that day forward, were able to listen in to AQIM chatter. A local interpreter helped them decode enemy movements and changing strategy.

The Chadians also took 24 prisoners and this group shed some light on the diversity of the militants operating in the mountain range. They included Hausa-speaking Nigerians, a Tunisian, a Burkinabé and a fighter who may have once been associated with the Polasario independence movement. The Tunisian fighter who had recently been trying to kill Chadians was hooked up to an intravenous drip and bandaged by Chadian medics.

The area was heavily mined with improvised explosive devices. During the next seven days, the Chadians lost three vehicles to land mines, but Mery said the totals could have been much worse without the work of the Chadian deminers who painstakingly cleared the pathway, digging out mines with spades.

From February 22 until March 3, the Chadians made a full circle of the Massif de Tigharghar, a 790-meter-tall rock formation, and cleared a 70-kilometer stretch known as the Valley of Ametetai, a terrorist stronghold. The contingent’s responsibility was to drive the fighters out of the valley toward the west where the tanks of the French 1st Marine Infantry Unit were positioned.

Movement was often difficult, with jagged rocks puncturing tires and mine detectors halting movement to investigate possible threats. In some places, the pathway shrunk to less than 5 meters wide, and whipping wind shot sand at piercing speeds. The extreme heat meant some Soldiers required 10 liters of water per day to stay hydrated. Visitors nicknamed the terrain Mars for its extraterrestrial appearance.

“The climatic conditions were really challenging,” said Gen. Bernard Barrera, French commander of Operation Serval. “It was 45 degrees Celsius every day, with some points higher than 50 degrees Celsius. Every one of our Soldiers was carrying more than 30 kilograms of equipment. Honestly, this is a sport for the young. These conditions provoked tendinitis, there were swollen hands, and we were hit with stomach illness.”

![Islamist militants who were captured in the Adrar des Ifoghas are held by Chadian forces in March 2013. [FATIM]](https://adf-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/BadGuys-929x1024.jpg)

During the clearing mission, French and Chadian forces found a veritable treasure trove of terrorist goods. They uncovered a Caterpillar-brand bulldozer parked under a tree and covered with branches. The vehicle had been used to dig pits for burying weapons, vehicles and land mines. There were piles of RPG tubes and little laboratories called “garages” in which explosive devices could be made. They found nitrate, a functioning generator and even explosive vests ready to be detonated. Scattered about were abandoned vehicles rigged to explode upon contact.

“We gave instruction to Soldiers not to touch anything,” Mery said.

Soldiers also found items of intelligence value, including satellite phones and computers. Phones were later analyzed by the French, and Mery was told they contained important contact information and call records. One of the most disturbing discoveries was the passport of Michel Germaneau, a French national who was taken hostage by AQIM and executed in 2010.

On March 1, Chadian forces announced the death of Abou Zeid, who was listed as the commander of the AQIM katibah, a group that controlled the trafficking and kidnapping activities in the Adrar. Having personally overseen the execution of at least two hostages and the kidnapping of more than 20, Zeid, an Algerian national, was considered among the most violent commanders in the AQIM hierarchy.

By March 4, the Chadians left the mountain range, and despite taking fire nearly every day and sleeping in difficult conditions, the men were exhilarated, Mery said. “Once we freed the Adrar, morale really was high,” he said. “Because the Soldiers were determined to succeed in their mission and it was a success. We lost men –– some of our best men, in fact –– but we brought victory to the Malian people.”

From March 11 to 28, the Chadians and French forces combed the mountain range again on a “ratissage,” or clearing mission, to look for stragglers, particularly in the area around the Ametetai Valley. On March 12, they had a skirmish with extremists, killing six and losing one Chadian Soldier.

By the end of the month, the FATIM and French forces were able to confidently say the Adrar was free of extremists for the first time in decades.

After the mission, the Chadians were welcomed home as heroes. President Déby declared May 13 a national holiday of “recollection and recognition.” “The values of peace and democracy that you embody and defend triumphed over fundamentalism,” Déby said.

When asked about the legacy of the intervention and the place in history, Bikimo was more modest. “We’re Soldiers with a capital ‘S,’ ” he said. “It was a political decision [to intervene], and certainly we are the ones who execute it.”

But he allowed himself a measure of satisfaction at a job well done. “We left Chad with pride and, thank God, the mission was completed with pride.”

Perspectives on an Intervention

On February 21, I spoke by telephone to Gen. Oumar Bikimo, commander of the FATIM. I told him this: “My general, you must push on! We cannot lose any more time, or the war risks becoming long and difficult.”

I said it for the simple reason that those who were fighting on the side of the Malian people –– aside from the French Army –– were too slow in joining us. That’s why I took the risk to send you into the fire, knowing that you would lose men. It follows the African adage, “When you want to kill a lion, you must go straight at him and not simply follow in his footsteps.” You went directly at the narcotraffickers, who were organized and war tested. Furthermore, they waited for you on the terrain they prepared in advance.

Your engagement lasted seven hours. You were at the heart of the operations. You had the means to save lives, thanks to your armored vehicles, but knowing that armored vehicles can’t scale hills, you decided to leave them behind and make the final assault on foot. This assault was certainly deadly, but it permitted the international community in Africa and in Mali to gain some time.

Without this assault, the war would have lasted at least six months. Thanks to this assault, you decapitated the horde of terrorists, you exterminated them, even if it was at a heavy cost.

The Chadian contingents depended for nearly six months on the funds of our own Chadian government. Whether it was the logistical domain or the financial domain –– there are always contributions from partner nations –– but the main effort was made by the Chadian government.

The lessons learned? You can’t separate them from one another. It’s all part of the life of the Chadian National Army now. It’s an experience, an experience that we lived through and now we must take away the positive and let fall what is negative. We hope there has been more positive than negative. Above all, it was a national mission.

It is true that the Regional Economic Communities, be it ECOWAS, ECCAS, SADC, along with the African Union, try to find solutions to the crises in Africa. Within the African Union, there is an architecture for peace that is being established. But you saw in Mali that it required the intervention of France and the intervention of Chad, who is not an ECOWAS member, to restore peace. ECOWAS has 15 members but was unable to mount a force to face the situation in Mali.

African institutions are working, but they don’t yet have the operational capacity to deal with situations such as terrorism. There is a movement to establish a Rapid Intervention Battalion, asking the states that have capacity to voluntarily participate in it. That’s still a project that is gestating; it hasn’t come to fruition yet.

Chad is a country that’s known civil war and foreign intervention on its soil. We are a country half Muslim, half Christian. And we’re very diligent about the peaceful cohabitation between the religious communities. We are a Sahelian country, like Mali. And we know that the challenges of terrorism don’t have borders, especially where no natural boundaries exist. The war imposed upon us meant that our Army has become extremely professional, especially in that terrain. Therefore Mali, ECOWAS, the international community and France strongly asked us to intervene. And there is a national consensus that we have to fight terrorism and fundamentalism, because it is likely to affect us as well. We paid a high price, more than 30 deaths, but I think that it was absolutely necessary.