ADF STAFF

When longtime Sudanese ruler Omar Al-Bashir stepped down in the face of a popular uprising, there was hope that a new era was beginning.

But as the country slides into chaos three years later, many believe that al-Bashir’s decades of poor governance and mismanagement of the military paved the way for the nation’s collapse.

Even in the heady days following the civilian uprising, some warned that the departing leader had left the country in a perilous position.

“The 30 years [of al-Bashir’s rule] were really horrible because that military dictatorship was very tough with the people — they arrested so many people, put them into jail, badly treated them in jail, even killed them,” said Mahjoub Mohammed Salih, retired editor of El Ayam newspaper, in an interview with Radio France Internationale.

Salih, who was 94 when al-Bashir left power and had lived through three military coups, said Sudan was in as bad a state as he could remember.

“The political parties are in bad shape, civil society is in bad shape, and the country and the economic situation are in tatters,” he said.

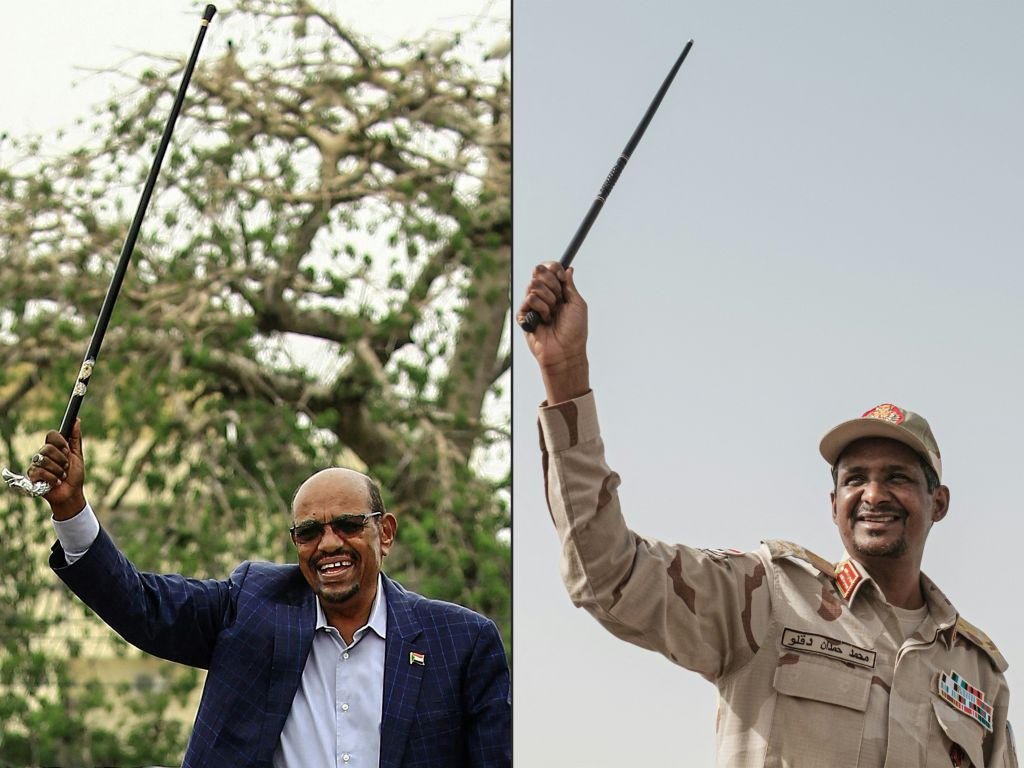

Perhaps most dangerous was al-Bashir’s creation of two rival armed forces. One, the Rapid Support Forces (RSF), is led by Gen. Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo, commonly known as Hemedti. He began as the leader of the Janjaweed militia during the early 2000s, unleashing scorched earth attacks against the people of Darfur. The campaign killed 300,000 and resulted in the International Criminal Court indicting al-Bashir for crimes against humanity.

In 2013, al-Bashir elevated Hemedti to be commander of the RSF, a paramilitary force. The RSF grew to include an estimated 100,000 soldiers and began challenging the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF), led by Gen. Abdel Fattah al-Burhan, for primacy.

“That’s the legacy of the al-Bashir era. Sudan has two de facto armies,” Suliman Baldo, director of the Sudan Transparency and Policy Tracker, told Le Monde. “Each has a nationwide strike force, has recruited across the country, has its own sources of funding and its network of international alliances.”

The two militaries that are now battling in the streets of Khartoum have incentives to defend their turf: There are millions of dollars at stake. Under al-Bashir, the SAF and RSF expanded to control businesses ranging from banks to gold mines to agricultural conglomerates. A report by the Center for Advanced Defense Studies identified 408 business entities controlled by members of the security sector.

For al-Bashir, allowing military and civilian elites to loot the economy was a way of protecting himself.

“Al-Bashir was able to stay in power for thirty years by fragmenting the security services and deftly playing them against each other to prevent any one of them from becoming powerful enough to launch a successful coup,” wrote E.J. Hogendoorn, former deputy Africa Program director at the International Crisis Group, in a piece for the Atlantic Council. “In return for their obedience, military and political leaders were allowed to gain control over large parts of the economy and accumulate great wealth.”

During the civilian-led transitional government that lasted from 2019 to 2021, anti-corruption leaders began dismantling al-Bashir’s patronage system by removing corrupt officials, investigating military-owned businesses and taxing them. Civilian Prime Minister Abdalla Hamdok called it “unacceptable” for the military to enmesh itself in the economy the way it had. Months later, he was deposed in a 2021 coup led by al-Burhan.

Analysts say this coup was the old guard protecting its interests.

“Bashir may have fallen in 2019, but his military successors have preserved much of his regime’s infrastructure,” wrote Willow Berridge, a lecturer at Newcastle University for The Conversation. “The remnants of this continue to undermine democratic transition in Sudan, with ultimately disastrous consequences.”