Adf staff

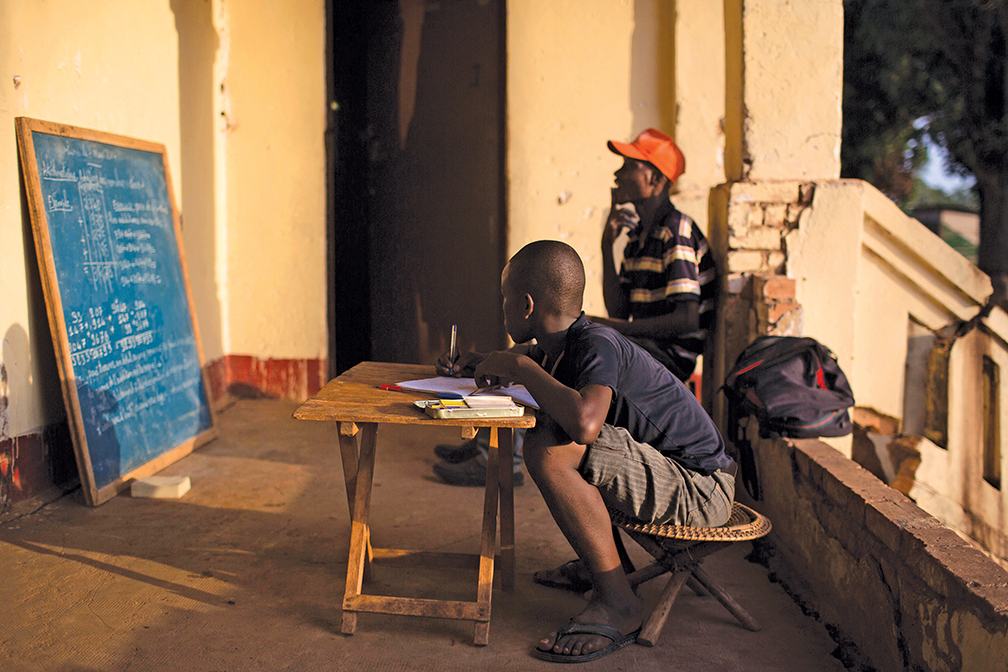

A young boy sits on a stool, stares at a chalkboard, and writes in his notebook. His classroom is the porch of a home built during French colonial times in Bangui, Central African Republic (CAR). His improvised school makes him more fortunate than many children in the nation. As hundreds of thousands of people have fled their homes since unrest spread across the land, schooling has become a casualty.

The CAR has been in turmoil since December 2012, when rebels overran the north and central regions. A March 2013 coup brought Michel Djotodia to power, and the country suffered a “total breakdown of law and order,” according to U.N. chief Ban Ki-moon.

Catherine Samba-Panza has since taken over as interim president, and France has increased its troop presence to 1,600 in hopes of stopping sectarian violence. The United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) says the number of internally displaced people has decreased recently, but 190,000 still were in about 57 camps around Bangui as of March 2014. Hundreds of thousands of others fled to Cameroon, Chad, the Democratic Republic of the Congo and the Republic of the Congo.

At one point in late 2013, 70 percent of CAR’s children still had not returned to school since the conflict began, according to UNICEF. Two-thirds of schools were looted, damaged or occupied. “A school is meant to be a safe space for teaching and learning, but in some areas there is nothing left,” said Souleymane Diabaté, UNICEF representative in the CAR. “Without teachers, desks, textbooks — how can a child learn?”

UNICEF and other nongovernmental organizations worked with the nation’s Ministry of Education to get more than 1,300 primary school teachers and 170,000 students back into classrooms by the end of 2013.

Petula Bokandi, 17, spent more than a month in the Boy-Rabe camp for internally displaced people outside Bangui. She said life in the camp is hard on children. Malaria is common. Most people sleep on mats on the ground. Blankets and mosquito nets are scarce.

In mid-January 2014, Bokandi returned to her home in the Gobongo neighborhood. Her room, which she shares with three sisters, doubles as a kitchen. She wakes up daily at 5 a.m., cleans house and works in the garden. “I left the camp because the violence in my neighborhood diminished,” she told UNICEF. “The situation here is calmer. You sleep well on a bed, with a mosquito net and a blanket. Over there, there is none of that. Here at our house it is less difficult.”

The violence separates children from their parents, communities and schools. Disease and the possibility of recruitment by warring groups also are threats. In camps like Boy-Rabe, UNICEF builds temporary learning spaces, but outside the camps education is stifled. There is no school because teachers don’t come to the area, and they are not getting paid. But that hasn’t stopped Bokandi from dreaming of becoming a banker one day.

“We have to stop the fighting among ourselves,” Bokandi said. “We have to put the weapons down so we can have peace so we can get back to work and school.”