ADF Staff

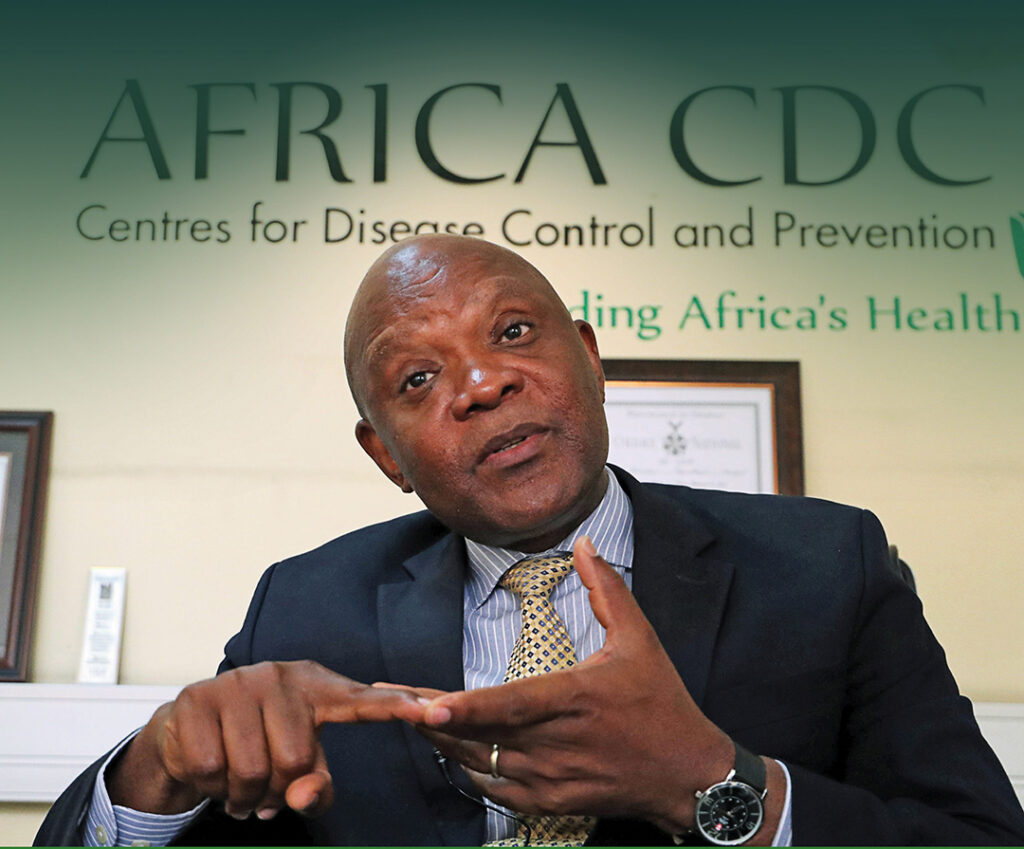

Dr. John Nkengasong, a virologist, has been the director of the Africa Centres for Disease Control and Prevention (Africa CDC) since 2017 and has helped lead the continent’s response to Ebola, COVID-19, malaria and other health challenges since that time. He spoke to ADF from his office in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, in December 2020. His remarks have been edited to fit this format.

ADF: Countries are now preparing to acquire and distribute COVID-19 vaccines. You recently co-authored a piece for Nature urging the world not to “let history repeat itself” where African nations find themselves at the back of the line when it comes to acquiring vaccines and lifesaving treatments. How can you ensure this doesn’t happen?

Nkengasong: Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance, and the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations are going to be instrumental in making sure that the initial vaccination is done almost simultaneously as much as possible across the world. It should not occur sequentially where the developed world gets vaccines, then Africa and the developing world get vaccines after that. It’s going to be extremely important to highlight the global solidarity and the oneness of the planet that we live on. Otherwise, the narrative will emerge that the rest of the world can wait, and some people will die, whereas people who have the money and resources have access.

So what does this mean? It is now incumbent on COVAX [the World Health Organization effort pushing for global access to the vaccine] to make sure that there are vaccination points within the major capital cities in Africa. That way our citizens have faith in the whole concept of global solidarity and global cooperation to get rid of this virus.

If the process delays until mid-2021 and people see on television that vaccination is happening in Europe, the United States, China, Russia, and no one has been vaccinated in Africa, then it will be a very unappealing impression.

ADF: You have a goal of reaching 60% immunization of the continent’s 1.3 billion people in two to three years. Aside from obtaining doses of the vaccine, what will be the biggest challenge in this effort?

Nkengasong: It is truly an unprecedented scenario we face. Remember, pandemic means this affects all of us, and this has never happened in the past 100 years. We need to be ambitious, or we will be judged harshly as the leaders of the continent who are here managing this crisis. There will be a next generation that will read the history of this pandemic, and a key question they will ask is: “Did the leaders have a stated, ambitious goal, and were they thinking outside of the box?” The crisis is unprecedented, and we have to have unprecedented strategies to allow us to reach 60%. This target is informed by science, informed by knowledge from other infectious diseases.

So I think the continent and partners need to do everything possible to take that to scale. The world has never vaccinated more than 500 million people in one year. But I think it is reasonable and the right thing to do. The saying is, “The time is always right to do the right thing.” We need to make sure that we mobilize the continent to get rid of this virus by vaccinating more than 60% of the population.

ADF: With any public health endeavor, education is a major component. In the past, we’ve seen suspicion and even hostility toward vaccinations. How can you help educate and reassure people about the safety of the vaccine?

Nkengasong: We looked at about 15 countries and saw a range of perception or willingness to accept the vaccine ranging from 60% to 80%. The question is: What can be done about the 20% to 40% of the population who are hesitant? We need to win this population over. We are very encouraged by the level of acceptance we’re seeing. In some parts of the developed world, acceptance of the vaccine is as low as 40%. This also points to the fact that we have a lot of work to do to get our population to believe in science, believe in the public health authorities, believe in public health institutions and agencies. They need to believe that leadership will watch their back and only allow safe vaccines to be administered on the continent. The Africa CDC is there just for that. It should be the trusted organization, as well as the World Health Organization, to communicate this information to the population.

ADF: Will the Africa CDC play a role in trying to prevent criminals from bringing fake vaccinations to the market?

Nkengasong: This is why we have insisted on the need for a whole-of-Africa approach to acquiring and distributing vaccines. This means that if a manufacturer approaches any member state, they should make sure that the Africa CDC is at the table to discuss it. We are also putting together a working group of regulatory agencies across the continent so we can speak with one voice. The whole-of-Africa approach calls for us to coordinate our activities as much as possible. If we do this, we can build barriers against and mitigate the potential for some companies to come in and do bilateral deals with countries and give them suboptimal vaccines. That has a tremendous risk of eroding the credibility of vaccines on the whole. Africa must express a strong unity of purpose in the spirit of cooperation and coordination through the Africa CDC, which is a specialized, technical agency of the African Union. This will be critical.

ADF: You recently returned from the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), which has endured disease outbreaks for many years. How have you seen countries use their experience in fighting previous outbreaks to be more prepared to take on COVID-19?

Nkengasong: There are three different layers to this. First of all, there is strong leadership on the continent, rallying around a cause at the level of the heads of state. Remember, the heads of state have met over the years to address the issue of HIV/AIDS and malaria. So, bringing back that level of leadership has been very important. The second is at the programmatic level, with the whole concept of using national public health institutes –– most of them were born out of the Ebola crisis in West Africa –– and this has been extremely important in coordinating the technical response to this pandemic. Third, at the more granular level, is the use of community health care workers in contact tracing. South Africa has thousands of community health care workers doing this. Uganda, Rwanda and Nigeria have done it similarly. We at the Africa CDC have supported these countries to [train and deploy] more than 10,000 community health care workers in 23 countries. That was born out of previous experience. It comes from the pains we have gone through in Ebola, where we used the community engagement to support contact tracing, education and isolation. So that has come in really handy.

ADF: One particular innovation by the AU and Africa CDC was the creation of platforms and programs to mutualize resources and leverage buying power among African nations. I’m referring to the African Medical Supplies Platform and the Partnership to Accelerate COVID-19 Testing (PACT). How have you observed cross-continental partnerships grow and deepen as a result of responding to this pandemic?

Nkengasong: This is new territory, and this is born out of a joint continental strategy that we put in place in February 2020. The first cases of COVID-19 were reported in Egypt on February 14, and on February 22 we convened a meeting in Addis Ababa with all the ministers of health. It was the first time we could rally more than 40 ministers of health and agree on a joint continental strategy. It is through that strategy that the platforms and mechanisms have been supported and endorsed. Behind the scenes there has been tremendous work for the acceptance of the platform, working with finance ministers, presenting it to the heads of state, presenting it to foreign ministers. So it may look just like a group of engineers came together and the platform was created, but there was a lot of work that went into it to carry the political leadership.

It was similar with the PACT initiative, as well as the AU COVID-19 Response Fund. Our hope is that, since this is a new territory, we will continue to strengthen them. They are not perfect, but they will grow and we will use them in an adaptive response to COVID-19. Hopefully, after this, we can continue to use those mechanisms to fight other endemic diseases like HIV, TB and malaria.

ADF: One bright spot in the COVID-19 response has been the way it has inspired innovation from individuals, companies and nations, from the use of drones and robots to the creation of apps to help with contact tracing and combating misinformation. What do you think about the innovations that have been made by African inventors and software developers?

Nkengasong: One of the early lessons we’ve learned is the power of innovation to fast track what has been called the “fourth industrial revolution.” Look at the technology platforms, look at the innovations that have come out of it. Before COVID-19, there was no country in Africa investing in developing basic diagnostics. Today, five countries are in that space: Morocco, South Africa, Kenya, Senegal and Nigeria. This is innovation that is happening within the last couple of months. Take personal protective equipment: Companies have been repurposed to manufacture masks and other material. We have seen a lot of that. I remain hopeful that behind every crisis there is a silver lining. As we say, “You don’t waste any crisis” in terms of advancing innovations, and we don’t want to wait until the next crisis before looking to innovation. This should create the space for technological advancement and also the local manufacturing of drugs and vaccines.

ADF: Even as the continent battles COVID-19, other health challenges continue, including malaria, HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis, diarrheal diseases and cardiovascular disease. Are you concerned that the effort to defeat COVID-19 will take away from combating those diseases, either by diverting resources or because people are delaying treatment?

Nkengasong: We are very concerned with that. We know that when pandemics hit, a lot of the deaths are not from the pandemic itself but are due to fact that the pandemic has shifted resources or the supply chain has been disrupted. It’s because of this that deaths are occurring in areas that are not necessarily related to the COVID infection. We are currently working with partners to do detailed analysis to see the impact. Very early on in the joint continental strategy we focused on three things: limiting transmission of COVID, limiting the deaths from COVID and limiting harm. In this case “harm” was defined to mean non-COVID diseases as well as economic harm. So we are conscious of that, and we continue to encourage our partners not to neglect things like immunization programs and programs for HIV, malaria and noncommunicable diseases. If you combine the deaths on the continent each year between HIV, TB and malaria, it is over 1.2 million people. So that would be a catastrophe if we allow the pandemic to impact those programs.

ADF: As you look to the future, what do you hope will be the next step in the development of the Africa CDC? How do you hope institutions build upon the lessons learned in combating COVID-19 to further develop continental health infrastructure and capacity?

Nkengasong: I believe that, not just the continent, but the world as a whole should step back and take a critical look at our public health security architecture. The Africa CDC should look at the challenges this pandemic has caused us and say, “How do we strengthen it further so we can truly be an empowering, continental organization that can make decisions quickly that are binding to member states?” The whole concept of health security should start at the national level. The Africa CDC can support member states to have their own national public health institutes that can work in a network and coordinate with the Africa CDC so we can guarantee a rapid response. Look at the DRC. How many times have we been to the DRC to fight Ebola? The Africa CDC is only 4 years old, and we’ve been there ever since I took office. If you have a strong national public health institution, then they can be fighting a pandemic locally and it will save us a lot. Look at how much we’ve spent on fighting COVID. If we used just a fraction of that on strengthening our systems, we would be ahead of the curve and save billions of dollars. I think that is where the reflection should be going.