ADF STAFF

In August 2022, an audio recording went viral on WhatsApp and social media networks in Burkina Faso. The message called on “indigenous” Burkinabé to rise up and exterminate members of the Fulani ethnic group.

Lionel Bilgo, a government spokesman, called the recording “chilling.”

“These are extremely serious words that are equivalent to the excesses of the Radio Mille Collines that led to the Rwandan genocide, one of humanity’s worst tragedies,” he wrote.

The incident was not isolated. Across the continent, clashes between Fulani herders and farming communities are fueling hatred and spawning wider violence. As Fulanis are isolated and stigmatized, they are vulnerable to recruitment by terror groups.

“The targeting of Fulani communities — based on the canard that they all support jihadi insurgents — is perpetuating the conflict, facilitating jihadi recruitment of Fulani, and risks spreading the violence,” Dakar-based researcher James Courtright wrote for Foreign Policy magazine.

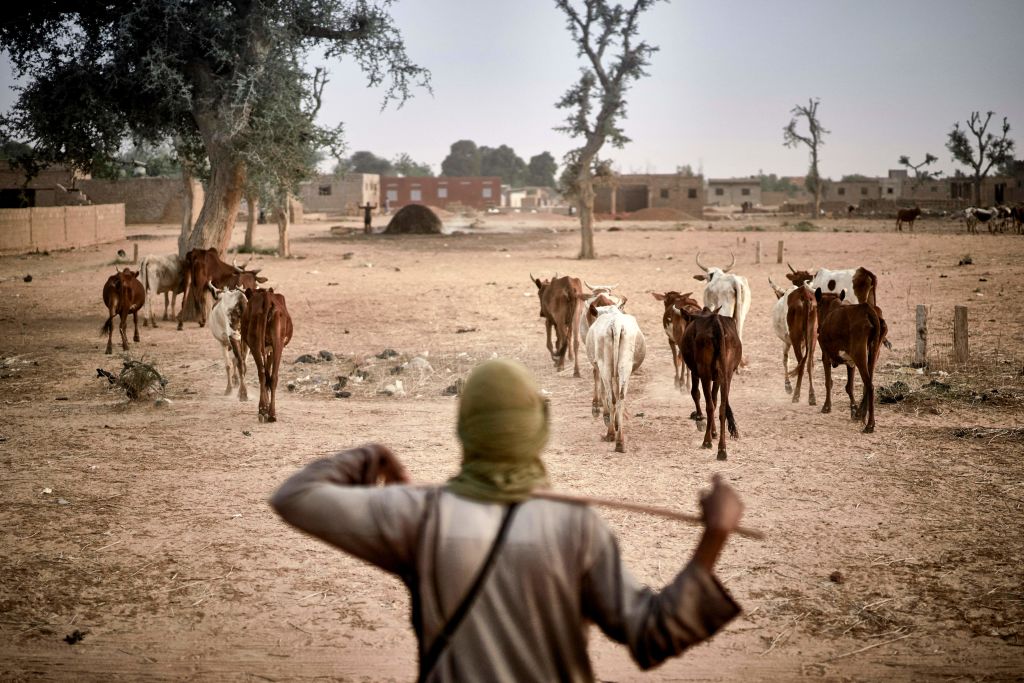

The Fulani are an ethnic group with a population of about 30 million stretching across the Sahel from Senegal to Sudan. Described as seminomadic, many still follow ancient traditions, herding cattle for hundreds of kilometers in search of grazing land.

In recent years some Fulani have been blamed for insecurity in Nigeria, Niger, Burkina Faso and Mali, a crisis that is sometimes termed a “Fulani rebellion.”

Fulanis hold top posts in several terror groups. The Malian terror group Front de Liberation du Macina (FLM) was founded by a Fulani preacher, as was the group Ansaroul Islam in Burkina Faso. Fulanis are well-represented among the ranks of the Islamic State of the Greater Sahara, Ansar Dine and Jama’at Nusrat al Islam wal Muslimin (JNIM).

But Fulanis have also disproportionately been the victims of Sahel violence. More than half of the civilians killed by the military or ethnic militias in Mali and Burkina Faso in 2022 were Fulani, according to data collected from the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project. Violence is fueled by racially charged radio broadcasts and social media posts that paint all Fulani as terrorists. The region has seen a rise in ethnic vigilante groups, including one in Nigeria that has committed extrajudicial killings of Fulani.

“When any group in a community feels alienated or subjected to any form of discrimination, it creates a fertile ground for social unrest, extremism and violent reactions,” Ghanaian security analyst Adib Saani said during a forum to address Fulani-related violence.

Pushed Together

The roots of the conflict in the Sahel are complex. Competition over scarce resources, marginalization and a need for protection from attacks are cited among the causes for Fulanis taking up arms.

“There are layers upon layers of this. It’s like an onion,” Aneliese Bernard, director of the consultancy firm Strategic Stabilization Advisors told ADF. “Climate change, and fast-growing populations and urbanization and drought –– all of these things really amplified and exacerbated the localized tensions that already existed.”

In recent years, herders and farmers have been pushed closer together in competition over shrinking patches of pasture. The result is often violence between the two groups. There were more than 15,000 people killed in farmer-herder conflicts in West and Central Africa between 2010 and 2020, and the death toll is on the rise.

“There is less land for people to farm on and less land for people to graze on,” Bernard said. “In the past 20 years, those spaces separating communities have rapidly shrunk. Now those communities are clashing over the remaining arable land.”

At the same time, widespread insecurity and the rise of violent extremist groups have led many Fulani communities to arm themselves. “The jihadist presence has forced groups, not just the Fulani but others as well, to reckon with the fact that the state is not going to provide them with adequate security,” Bernard said. “So these communities either need to side with the jihadists for provisional security or set up a communal militia for self-defense.”

Terror groups are seeking to capitalize on this sense of isolation. Amadou Koufa, the founder of the FLM, in particular has tried to portray himself as the protector of Fulani. Observers fear that radical groups are making inroads among Fulani communities in coastal countries like Côte d’Ivoire, Ghana, Togo and Benin.

‘Come Home Safely’

There is no simple solution to the problem, but Bernard said programs that create a pipeline for combatants to defect and reintegrate have had some success in Niger. The key, she said, is for communities on the conflict’s frontlines as well as military and government officials to play a role in encouraging fighters to lay down arms.

“You want to encourage them to feel that they can come home safely, because if the process functions safely and efficiently, it serves as a feedback loop – they’ll tell their friends,” Bernard said.

In recent years, the Nigerien government has also sponsored intercommunal dialogue and mediation efforts to promote cross-cultural understanding. It is unclear how Niger’s recent coup and political upheaval will impact these programs.

“It requires a persistent effort, but not a ton of resources to implement,” Bernard said. “You have to keep it up, because if it stops then everything falls apart.”