A Study of Boko Haram’s Public Communications Can Offer Hints About Its Strategy

ADF STAFF

In July 2011, the Nigerian government unveiled plans to make telecommunications companies dedicate toll-free phone lines so civilians could report Boko Haram activity. Months later, insurgent spokesman Abu Qaqa threatened to attack service providers and Nigeria Communication Commission (NCC) offices.

“We have realized that the mobile phone operators and the NCC have been assisting security agencies in tracking and arresting our members by bugging their lines and enabling the security agents to locate the position of our members,” Qaqa announced, according to a 2013 article by Freedom Onuoha on the E-International Relations website.

Eight months later, Boko Haram made good on Qaqa’s threat. The militant group launched a two-day attack on telecommunications towers belonging to several providers in five cities: Bauchi, Gombe, Kano, Maiduguri and Potiskum. Qaqa announced that Boko Haram launched the tower attacks “as a result of the assistance they offer security agents.” Of the 530 telecommunications base stations damaged in Nigeria in 2012, Boko Haram was responsible for 150.

“The other is I think it’s a pretty powerful message if Boko Haram comes out and says, ‘I’m going to attack X because of this,’ and then they go out and they do it,” Mahmood said. “It just serves to make their next warning even more intimidating and effective.”

MESSAGES PORTEND ATTACKS

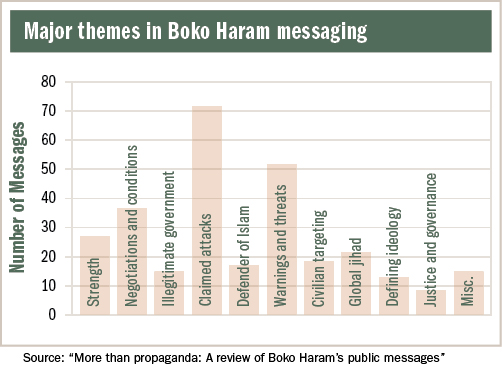

Mahmood, in his March 2017 paper for the ISS titled “More than propaganda: A review of Boko Haram’s public messages,” showed that a significant number of Boko Haram messages between 2010 and 2016 issued warnings and threatened violence. In fact, warnings and threats constitute the second-most-common theme of the group’s messaging out of the 145 messages studied.

“Given the proliferation of warnings in Boko Haram messaging, especially during [leader Abubakar] Shekau’s extended rants in which he accuses essentially all opposed to him, it can be difficult to discern between a legitimate threat and bluster,” Mahmood wrote. “But a careful reading of the situation may determine what Boko Haram’s next target could be, which is more likely to result in action when linked to a specific and articulated grievance.”

Boko Haram demonstrated this tendency further in its threat against schools. In January 2012, Shekau complained publicly about alleged mistreatment of Islamic schools and students, and he threatened to launch attacks.

Again, Boko Haram followed through. From January to early March 2012, militants destroyed at least a dozen schools in the Maiduguri region of Borno State. About February 20, 2012, the first three schools were set ablaze. Six days later, Boko Haram said the attacks were in retaliation for state raids on Islamic schools, according to Human Rights Watch. From February 26 to 29, militants burned at least four schools, and on March 1 torched another five.

Again, Boko Haram followed through. From January to early March 2012, militants destroyed at least a dozen schools in the Maiduguri region of Borno State. About February 20, 2012, the first three schools were set ablaze. Six days later, Boko Haram said the attacks were in retaliation for state raids on Islamic schools, according to Human Rights Watch. From February 26 to 29, militants burned at least four schools, and on March 1 torched another five.

Ties between messaging and attacks also can be seen in Boko Haram’s assault on Nigerian media and the nation’s oil industry. As Qaqa complained that the media misrepresented Boko Haram, insurgents bombed This Day newspaper offices in Abuja and Kaduna in April 2012. Boko Haram’s anger at This Day stemmed from a 10-year-old column on the Miss World pageant published in the paper, which some Muslims found to be blasphemous. Peaceful protests already had taken place in the runup to the pageant, but the column sparked violent clashes between Christians and Muslims that resulted in about 250 deaths, according to Human Rights Watch.

The 2002 pageant, originally scheduled to be held in Nigeria, eventually was moved to London, but Boko Haram’s anger culminated in the attack years later.

A month after the This Day attack, Boko Haram issued an 18-minute video that sorted Nigerian media into three groups based on its perception of their transgressions. This Day stood alone in the first tier because of the Miss World incident and other perceived offenses. The second tier included several newspapers and a radio station. These outlets would be attacked soon, the narrator stated. The third category included media organizations that faced attack if they were not careful, listing more newspapers, an international radio service and a website.

In June 2014, a suicide bomber detonated a bomb outside a Lagos oil refinery. Mahmood wrote that the decision to attack the refinery so far from Boko Haram’s home base likely was an assault on government wealth sources rather than evidence of a grievance with the oil industry. Similar attacks did not follow, and oil interest messaging rarely has been repeated. “Rather than emerging out of nowhere, the assault was foreshadowed in Boko Haram messages in February, March and May that year [2014], indicating its commitment and ability to follow through even on pledges considered to be unrealistic at the time,” Mahmood wrote.

HOSTAGES AND PRISONERS

Boko Haram’s highest-profile action is the kidnapping of 276 Chibok schoolgirls in 2014. On April 14, militants attacked a boarding school in Chibok, Borno State, in the middle of the night. Insurgents raided dormitories, loaded girls into trucks and drove away. Some girls jumped into bushes as trucks rushed away, leaving 219 children held captive. The atrocity drew worldwide condemnation and parallels a long-standing grievance of Boko Haram: the desire for the release of incarcerated members.

Negotiations and conditions comprise the third- most-frequent theme appearing in messages Mahmood studied. “Specifically, the demand for all incarcerated Boko Haram members to be set free has been a recurrent refrain in messaging,” he wrote.

In the rampup to the Chibok abductions, Shekau referenced the wives and children of insurgent detainees no less than seven times in 2012 and 2013, and accused federal officials of kidnapping insurgents’ family members. In 2012, spokesman Qaqa stated: “We would soon start kidnapping the wives and children of all the people that have had hands in the arrest of our wives and children.”

In the rampup to the Chibok abductions, Shekau referenced the wives and children of insurgent detainees no less than seven times in 2012 and 2013, and accused federal officials of kidnapping insurgents’ family members. In 2012, spokesman Qaqa stated: “We would soon start kidnapping the wives and children of all the people that have had hands in the arrest of our wives and children.”

In October 2016, after months of negotiations, Boko Haram released 21 of the Chibok girls in exchange for a monetary ransom, Daily Trust reported. In May 2017, insurgents swapped another 82 of the girls for five militant leaders.

EXPANDING VIOLENCE, JOINING ISIS

Boko Haram grew as a local insurgency from 2009 to 2012. In 2013, a willingness to expand into regional operations emerged with the kidnapping of a French family in Cameroon, the insurgent group’s first foray across the border of Nigeria’s neighbor. The kidnapping, the group said, was a response to the arrest of Boko Haram members in Cameroon. From there, operations increased in Cameroon in 2014, and by early 2015, Shekau was openly taunting the presidents of Chad and Niger as well.

“This coincided with the first violent Boko Haram operations in both countries in February 2015, again demonstrating the close convergence between messaging and group action, and confirming the extension of its struggle to the Lake Chad region,” Mahmood wrote.

It was about this time that the insurgent group pledged its allegiance to ISIS. A new Arabic-language Twitter account claiming to be the official outlet for a new Boko Haram media group launched, called Al-Urwah al-Wuthqa, the BBC reported.

The ISIS alignment was the beginning of big changes in messaging for Boko Haram. Until then, messaging was closely associated with what the group was going through or accomplishing. Ernest Ogbozor, a Nigerian doctoral student at George Mason University in the United States, said his research points to three distinct phases of Boko Haram messaging, culminating with the ISIS alignment.

The first phase, roughly from 2009 to 2012, focused on grievances, recruitment and revenge. In 2009, Nigerian forces killed founder Mohammed Yusuf, destroyed mosques and disrupted a micro-credit lending scheme. “Now the group was left with nothing,” Ogbozor said, adding that messaging sought to parlay these grievances into popular support.

The first phase, roughly from 2009 to 2012, focused on grievances, recruitment and revenge. In 2009, Nigerian forces killed founder Mohammed Yusuf, destroyed mosques and disrupted a micro-credit lending scheme. “Now the group was left with nothing,” Ogbozor said, adding that messaging sought to parlay these grievances into popular support.

Boko Haram’s most powerful period was from 2013 to 2015, when it was capturing and holding territory, and dealing setbacks to military forces. Messages at this time focused on praise for territorial and military achievements.

By late 2015 and through 2017, Nigerian and regional military assaults began to take their toll on Boko Haram. “So instead of praising itself, the message changed to seeking relevance,” Ogbozor said. “This is when Boko Haram pledged allegiance to Islamic State.”

GROUP, MESSAGING SPLIT

In August 2016, Boko Haram split into two factions: One is led by pugnacious spokesman Shekau; the other by Abu Musab al-Barnawi, ISIS’ choice for leader. Although Shekau pledged allegiance to ISIS in 2015, the group soon grew tired of his management of the war against regional forces and his propensity for targeting civilians, Mahmood said. The al-Barnawi faction broke off, and with this change came differences in messaging.

Shekau had been featured prominently in Boko Haram messages. Soon after pledging allegiance to ISIS, that ended. Al-Barnawi’s faction started releasing themed batches of photos through social media that highlight nonmilitary aspects of the group’s struggle, such as governance, justice and services that Boko Haram can provide as part of ISIS.

The split also has left al-Barnawi’s ISIS-aligned faction the clear winner in terms of potential longevity and lethality, Mahmood said. Shekau’s wing is just trying to survive, but it still uses ISIS logos in messages.

RECOMMENDATIONS FOR ACTION

Mahmood said more research is needed to see how Boko Haram messaging resonates with local populations. It’s possible, he said, that Boko Haram messaging might not be particularly effective locally. If so, then countermessaging efforts may not work either. However, he writes: “Boko Haram messaging provides a window into a group that otherwise remains largely enigmatic and obscure. … Messaging can thus expose important insights beyond simply serving as a propaganda tool, and thus should be closely monitored.” He suggests that observers:

- Continue researching the effects of Boko Haram messaging on local populations, focusing on recruitment. Doing so will lead to more effective programs to reduce this influence.

- Analyze Boko Haram messages to see changes in group divisions or the identification of new targets.

- Continue frustrating Boko Haram messaging by detaining media operatives or removing social medial posts. Such tactics can reduce messaging or discontinue certain practices, such as social media use.

- Reduce penalties and stigmatization for those who watch Boko Haram messages to keep from enhancing its appeal. Long-winded rants may actually present the group as negative and volatile.

- Balance factual press coverage of Boko Haram messages with the need to limit its outreach. Careful reporting guidelines can keep the media from becoming a propaganda tool.

“The messaging says a lot about their strategy,” Mahmood said. “It goes hand in hand, so it’s important to really look at these aspects because they can tell you a lot about the movement.”