ADF STAFF

More than 4,000 years ago, the pharaohs of Egypt established a trading partnership with the prosperous Land of Punt. The Egyptians kept the location of the kingdom a secret. They would travel vast distances on land and sea to trade with the country, which they regarded as Ta Netjer — God’s Land.

The earliest known direct references to Punt come from the Palmero Stone, a tablet that contains accounts of the ancient Egyptian dynasties. The stone’s inscriptions say that during the reign of King Sahure, about 2450 B.C., traders led a profitable expedition to Punt, returning with myrrh, gold, silver, timber and slaves. It is the first record of Egyptians traveling there.

The Land of Punt mostly was hidden from the rest of the world because of its isolation. The citizens of Punt were eager to trade for the Egyptians’ tools, jewelry and weapons. In exchange, the Egyptians received ivory, ebony, gold, elephant tusks, incense and wild animals, including baboons.

But each journey to the Kingdom of Punt was long and difficult. Over the centuries, the trading partnership faded, then stopped altogether. The Egyptians lost track of Punt’s location. It faded from memory, believed to be somewhere along the Red Sea, or farther south. But no one knew for sure.

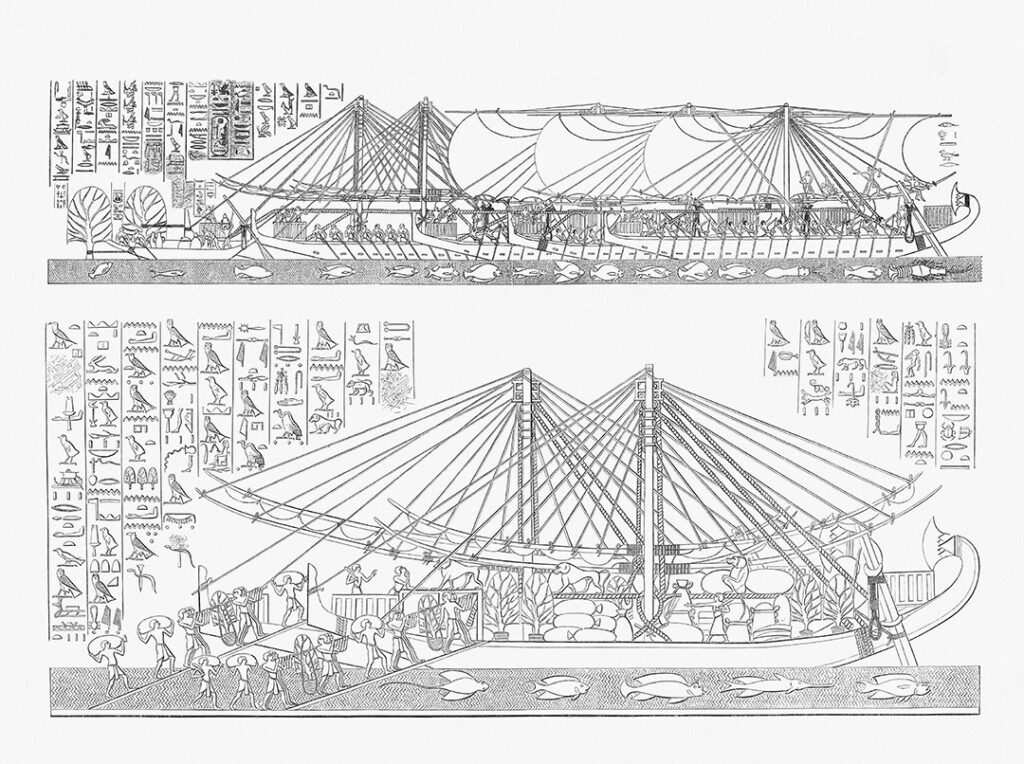

When Queen Hatshepsut became the pharaoh of Egypt about 1470 B.C., the route to Punt had been lost for decades. Hatshepsut told her subjects that the gods had directed her to find the route by sending a trade mission. The expedition began in about her ninth year as pharaoh, when she dispatched five ships, each 21 meters long. The 210 men sent on the trip included sailors and rowers.

The journey was a fantastic enterprise. The Egyptians traveled down the Nile, took apart their ships and carried them across land to the Red Sea, where they reassembled them. The portable ships were light, but they also were fragile, and had to keep to the safer shallow shores of the Red Sea. The trip at sea took about 25 days, covering 50 kilometers per day.

The successful trip thrilled the citizens of Punt, who knew how dangerous the Egyptians’ journey had been. The Egyptians returned from the trip with the expected vast wealth, but they also had 31 myrrh trees, each with its roots in a basket. Hatshepsut had the trees planted in the courts of her mortuary temple complex, where they thrived — the first time in recorded history that anyone had successfully transplanted foreign trees. The roots of the trees still can be seen to this day.

Trade with the Kingdom of Punt continued into Egypt’s New Kingdom era. But over time, regional politics and empire-building took priority over dangerous long-distance trade. By about 1100 B.C., Punt had once again become a lost land of mystery. Egyptologist Joyce Tyldesley has described Punt in the post-New Kingdom time as “an unreal and fabulous land of myths and legends.”

Over the years, historians and scientists developed theories as to the location of the lost kingdom. They came to believe that Punt was on the Horn of Africa, possibly in what is now Ethiopia. Other possibilities included Djibouti, Eritrea, Somalia, southern Sudan and even Yemen. Some researchers have theorized that Punt might have been another name for a port city the Romans called Adulis in what is now Eritrea.

In 2020, a team of researchers achieved a breakthrough when they examined radioactive isotopes in the mummified remains of baboons in Egypt dating to the New Kingdom and the Ptolemaic period, 305 to 330 B.C. The scientists discovered that some of the animals were not native to Egypt but likely were from the Horn of Africa. Because they knew the Egyptians got baboons from Punt, they were able to narrow the location.

One particular baboon, a female, had salvageable DNA, which was traced to the Adulis region. Although the study does not close the book on the location of Punt, it almost certainly puts it in what is now Eritrea. The discovery might help historians unlock secrets from this long-lost civilization.