As the Stubborn Disease Continues in the DRC, Responders Must Build Trust to Succeed

Dr. Jean-Christophe Shako went to Butembo, Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), to fight a fierce and dangerous enemy.

But first he needed to make a friend.

Shako, Ebola response coordinator in the eastern DRC town, is a veteran of four Ebola outbreaks in Africa. He wrote of his experiences with the current disease crisis in February 2019 for The New Humanitarian, an online news outlet. He recalled his team’s experience in Guinea during the height of the West African pandemic in 2014. It was then that villagers, suspicious of the outsiders who spoke of a mysterious killer disease, came after them armed with machetes.

Nearly five years later and nearly 5,000 kilometers away, Shako faced the same threat. “It only took a few days in Butembo, responding to the current outbreak in eastern Congo, before I was surrounded by an angry mob chanting, ‘Kill him,’ after they refused to allow our surveillance team to investigate a death in their neighborhood.”

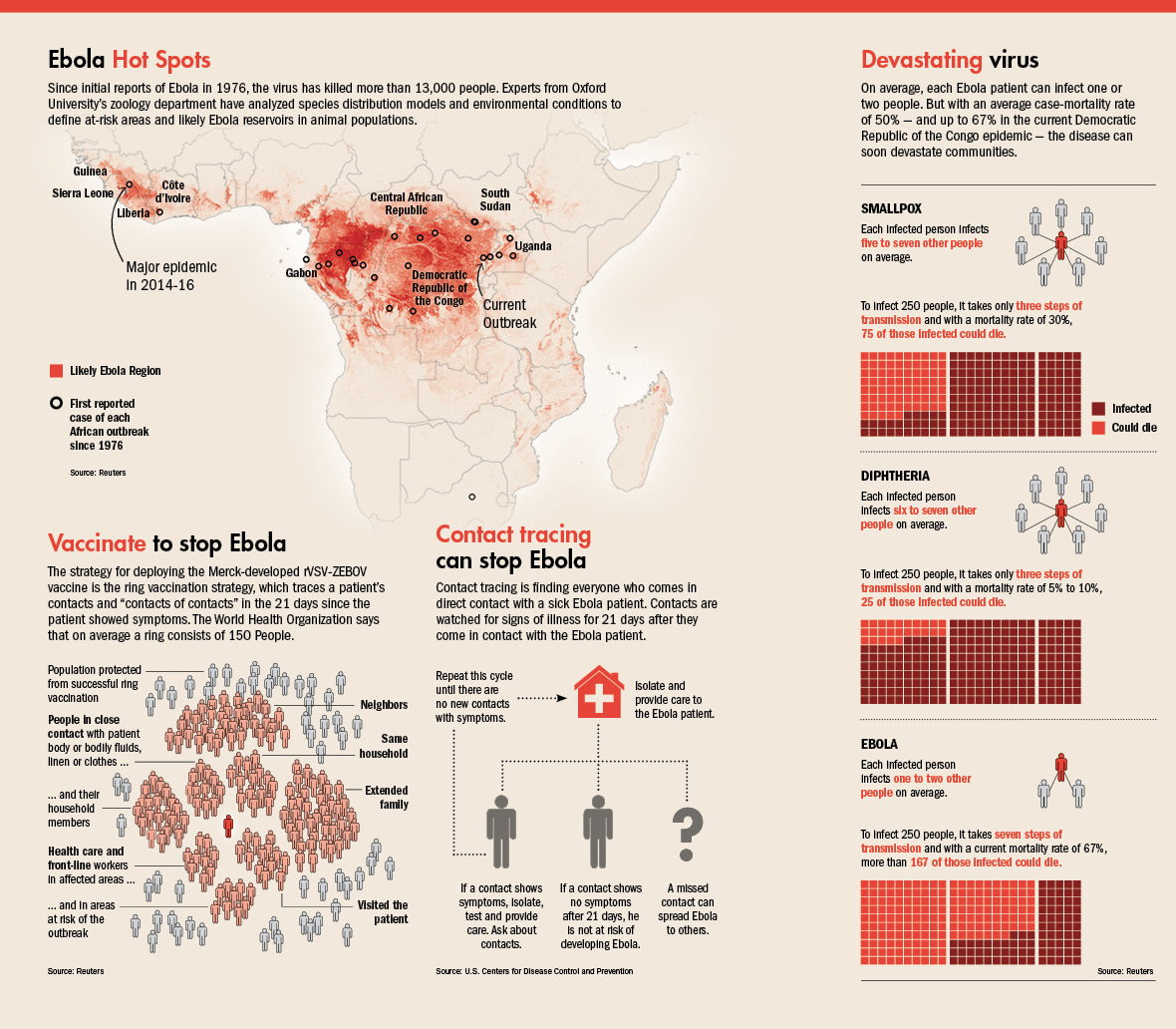

Ebola was back for the 10th time in the DRC and the second time in less than a year. An outbreak in Equateur province between May 8 and July 24, 2018, led to 54 cases and 33 deaths. By August 1, 2018, a new outbreak erupted in North Kivu and Ituri provinces in the east. It has been more deadly and intractable for those fighting it, despite new tools, such as vaccines.

By June 10, 2019, there were 2,071 confirmed and probable cases reported, and 1,396 people had died — a mortality rate of 67%. The majority of cases were women and children, and 115 health care workers caught the disease. Dozens had died. The outbreak is the second-worst since Ebola was discovered in 1976. Only the West African pandemic was more deadly.

An already fearsome disease is complicated by the remoteness of the affected provinces, their proximity to other countries such as Uganda and Rwanda, and the scores of armed groups operating in the region. Expertise and effective vaccines are helping, but as Shako knew, success would require a dose of humanity.

A DANGEROUS EPICENTER

Workers were able to vaccinate 73,298 people by January 27, 2019, according to the DRC’s Ministry of Health. That is a vital tool for blunting the spread of the highly contagious disease, which is transmitted from person to person through bodily fluids such as blood, feces and vomit. During the West African outbreak in Guinea, Liberia and Sierra Leone, the disease spread in large part because of burial and funeral traditions that had villagers touching, kissing and washing the bodies of their dead. There was no vaccine for most of that outbreak, and the disease made its way to bustling urban centers such as the Liberian capital, Monrovia.

West Africa was experiencing relative peace during the Ebola outbreak, although there were incidents of violence by skeptical and fearful villagers in more remote areas. But the eastern DRC provides a much different landscape for the disease.

Scores of armed groups roam the mostly ungoverned spaces of the DRC’s eastern expanse. Colonial structures and years of corrupt leadership after independence have left the region troubled and violent. Some of the armed groups originated in neighboring countries, such as the Allied Democratic Forces, which came out of Uganda. The Democratic Forces for the Liberation of Rwanda, Hutu rebels who oppose Tutsi rule in Rwanda, also have taken root in the eastern DRC. Other armed groups are present, and the large United Nations Organization Stabilization Mission in the DRC works to keep the peace.

Fighting Ebola in a conflict zone is dangerous for local civilians and health workers alike. “Once a village is attacked, there’s a movement of people, so the sick person moves, and the disease spreads from one village to another,” Justus Nsio Mbeta, a representative of the Ministry of Health in the village of Beni, told Vice News in February 2019.

Fighting Ebola in a conflict zone is dangerous for local civilians and health workers alike. “Once a village is attacked, there’s a movement of people, so the sick person moves, and the disease spreads from one village to another,” Justus Nsio Mbeta, a representative of the Ministry of Health in the village of Beni, told Vice News in February 2019.

One of the most common ways to approach an Ebola outbreak is through what is called “contact tracing.” This is when health officials track down everyone who has had contact with an Ebola sufferer. Those people are then watched for 21 days from the last day they were with the Ebola patient to see whether they develop symptoms. If so, they are isolated and treated, and the tracing cycle continues with other contacts until there are no new contacts with symptoms.

When armed attackers raid a village or attack an Ebola treatment center, it increases the likelihood that the disease will spread and complicates contact tracing. On February 27, 2019, unknown armed assailants attacked a treatment center in Butembo, setting a fire and trading gunfire with security forces.

Health officials said that 38 suspected Ebola patients and 12 confirmed cases were in the center when it was attacked. Four people, each with confirmed cases of Ebola, ran away. Just three days earlier in the nearby town of Katwa, assailants set fire to a treatment center, killing a nurse, Reuters reported.

On April 20, 2019, militia members attacked a treatment center and tried to burn it down. A day earlier in Butembo, attackers killed a Cameroonian epidemiologist, The Washington Post reported.

RUMORS HINDER EFFORTS

A report from the DRC’s Ministry of Health indicates that the proportion of known contacts improved from 24% to 63% between October and December 2018, but this dropped to about 10% in mid-January 2019 because of security and political disruptions.

The ministry recommends methods to strengthen monitoring of displaced contacts for those who have been lost to follow-up. Ways include forming mobile surveillance teams to find lost contacts, bolstering psycho-social support for identified contacts to encourage participation, and training coordinators to use technology to monitor workers involved in contact tracing.

However, such efforts will be difficult without a way to counter the rampant rumors that circulate in areas affected by Ebola. In a nation beset by instability, deadly violence and mistrust of the government, news of the mysterious disease often is greeted with suspicion.

A study published in the journal Lancet Infectious Diseases surveyed 961 people in the cities of Beni and Butembo. It found that more than a quarter of people did not believe Ebola existed. More than a third — 36% — said the disease was fabricated to destabilize the DRC. Researchers questioned people in September 2018 and published results in late March 2019.

These views came as DRC officials used the Ebola outbreak as a rationale for postponing the region’s participation in national elections. The rest of the country voted in December 2018, selecting a new president who took office in January 2019. More than a million people in areas affected by Ebola couldn’t vote until March 31, 2019, and then only in parliamentary contests.

NBC News reported in mid-April 2019 that some locals believed the response was a money-making scheme called “the Ebola business.” Treatment centers are accompanied by security forces, which also raises concerns. The outbreak’s proximity to national elections had some believing it was an excuse to keep voters from the polls. After the vote, however, conditions seemed to improve.

Aid agencies also are taking extra steps to assuage fears among locals. Eva Erlach, who heads the regional community engagement program for the International Federation of the Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (IFRC), told NBC News that the organization is using transparent body bags “to show the family that it is actually their loved one that is being buried, and it’s not stones or empty coffins.”

Decisions such as that are based on information culled from 800 IFRC volunteers who have collected 150,000 comments for a database that is shared with other relief organizations. “Ultimately, if you don’t connect with communities, it doesn’t matter how efficient the treatment system is,” Tariq Reibl of the nonprofit International Rescue Committee told NBC News.

ENGAGING FACE TO FACE

As Dr. Shako found himself surrounded by the threatening mob in Butembo, his experience helped him keep his composure and respectfully deescalate tensions. Less than two months after arriving in the city, responders heard about a baby boy who died from Ebola in the village of Tinge, which was controlled by the dangerous Mai-Mai militia. Shako told his team they would have to go to Tinge to vaccinate people. He, a nurse and a driver set out on the 45-minute ride, followed by a 35-minute walk. Dozens of villagers had gathered to mourn the baby.

“We were greeted by a woman who asked what we were doing in their village,” Shako wrote. “I told her I had to see the village chief because I had something important to tell him. She pointed me to his house.”

In the house were five men, including the chief, seated at a dining table. They invited Shako to join them at the table, where they shared a meal of pondu (cassava leaves), fufu (cassava flour and water) and a piece of meat. As Shako ate, the mood lightened and a conversation began. Shako spoke of Ebola and vaccination, which the men had not heard of. He told how the virus spreads and how to prevent it.

“Without saying a word, the village chief went outside and gathered the villagers. He said a few words in their local dialect while making big gestures,” Shako wrote. “Then he allowed the [nurse] to list all those who had been in contact with the baby boy so we could follow the chain of transmission. In total, 75 people came forward.”

The next day, everyone was vaccinated. “Not a single person in that village developed the virus,” Shako wrote.

Shako’s contact with one village chief built enough goodwill that he was able to meet with more, answering questions and gaining trust. The DRC’s minister of health spoke with another Mai-Mai leader, who pledged that his fighters would not hinder Ebola efforts.

“Earning trust during such a deadly outbreak is always hard,” Shako wrote. “Which showed me yet again that respect, compassion, and humility can go a long way — even saving your life and the life of an entire community.”