ADF STAFF

Even without adequate access to COVD-19 vaccines, there are ways African nations can mitigate the pandemic’s spread.

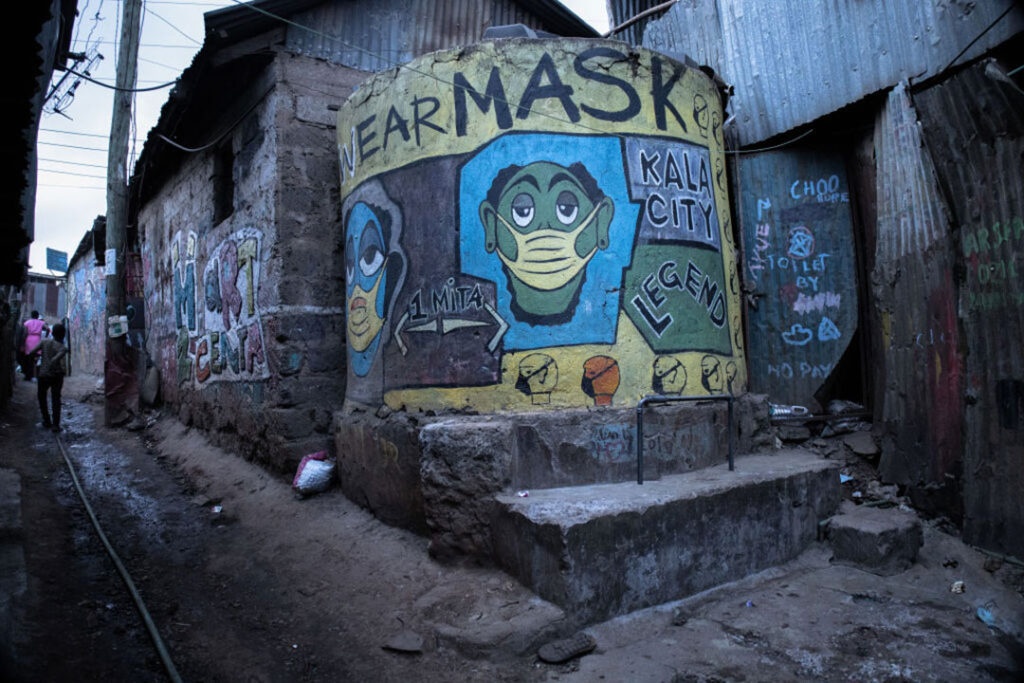

Beyond lockdowns, quarantines, mask wearing, social distancing and other preventive measures, the key to fighting COVID-19 and future disease outbreaks may lie in community education and engagement.

Writing in The Conversation Africa, epidemiologist Deoraj Caussy, a lecturer at Open University in Mauritius, said that the spread of disease can be slowed when people are motivated to spot and report clusters of cases. This community vigilance helps health care workers take early action.

“Citizens must be empowered through education and community leadership to recognise a cluster of cases before the disease has time to spread in institutions or communities,” Caussy wrote. “Citizens act responsibly when they are provided with the right information. They will feel that they are contributing towards the national good of public health protection and not just for their own self-interest.”

That community buy-in will occur only when pandemic information is shared in easy-to-grasp language and when key figures who shape public opinion are part of the effort.

“Education must be in local vernacular to target the population at risk, including frontline workers and people with medical conditions with increased vulnerabilities,” Caussy wrote. “We must dispel misinformation that negates the public health measures through classic information education and communication methods to include role model figures like artists, tribal chiefs and other community leaders.”

There is an urgent need for homegrown solutions as countries with limited vaccine access now face a third wave of the virus.

In early June, the World Health Organization (WHO) reported that 47 of Africa’s 54 countries were set to miss the September target of vaccinating 10% of their populations, unless Africa receives 225 million more COVID-19 vaccine doses. Hot spots were identified in Egypt, South Africa, Tunisia, Uganda, Zambia and nine other Sub-Saharan countries.

Africa has received about 32 million doses — less than 1% of the more than 2.1 billion doses administered globally. Only 2% of Africa’s nearly 1.3 billion people have received one dose, and only 9.4 million Africans are fully vaccinated, according to the WHO.

“As we close in on 5 million cases and a third wave in Africa looms, many of our most vulnerable people remain dangerously exposed to COVID-19,” Dr. Matshidiso Moeti, the WHO’s regional director for Africa, said in a news release. “Vaccines have been proven to prevent cases and deaths, so countries that can must urgently share COVID-19 vaccines. It’s do or die on dose sharing for Africa.”

One way African nations are taking action is by increasing production of medical-grade oxygen. Since the start of the pandemic, the number of oxygen-generating plants has grown from 68 to 119 in Africa, and the number of oxygen concentrators has more than doubled to 6,100, the WHO reported in March.

In January, Nigerian President Muhammadu Buhari approved a $17 million project to build 38 oxygen plants across the nation. The government earmarked an additional $671,000 to repair oxygen facilities in five hospitals.

Boss Mustapha, chairman of Nigeria’s Presidential Task Force on COVID-19, said at least one new oxygen plant will be built in each state and that existing ones will be upgraded to become fully functional, according to the Nigerian newspaper The Vanguard.

In April, Tanzania installed medical oxygen production plants at its seven largest national hospitals in a project backed by the World Bank. New President Samia Suluhu Hassan altered Tanzania’s COVID-19 response after the March death of President John Magufuli, a staunch COVID-19 skeptic, who had refused to seek vaccines.

Continental leaders have said the pandemic is a wakeup call for the need to create more resilient health systems. A resilient health system is defined as one that can withstand the shock of a major health event and quickly adapt to meet new challenges.

This can be done through increased technology use and strengthened public-private partnerships, a study by BMJ Global, an online peer-reviewed medical journal, concluded.

Strengthening health care systems also requires cooperation among African nations, Dr. John Nkengasong, director of the Africa Centres for Disease Control and Prevention, told Devex.com.

“We need people-centered health systems that are very inclusive and begin to disrupt the tendency of dependence of the global south on the global north,” Nkengasong said. “We have to disrupt that by regionalizing our health security architectures.”