ADF STAFF

When it comes to pandemic diseases, the African continent has been forged in fire.

History is replete with examples of deadly illnesses originating on the continent and ravaging populations in nation after nation. Some, such as Ebola, rear their heads fiercely in specific regions at different times, killing and terrorizing populations while the world looks on in fear.

Others, such as HIV/AIDS, stubbornly take root in a region and become an endemic health concern for generations, not unlike the ever-present threat of malaria or yellow fever.

A few, however, emerge elsewhere and march across the globe, infecting Africa from every direction and with methodical, relentless and increasing intensity. COVID-19 is such a disease. And although this coronavirus is new, its similarities to an infectious precursor — the 1918 Spanish flu — are instructive.

Africa has been through a catastrophic, global pandemic before. The question is, what lessons can be learned from a plague that coursed through the continent more than 100 years ago?

It Began With World War I

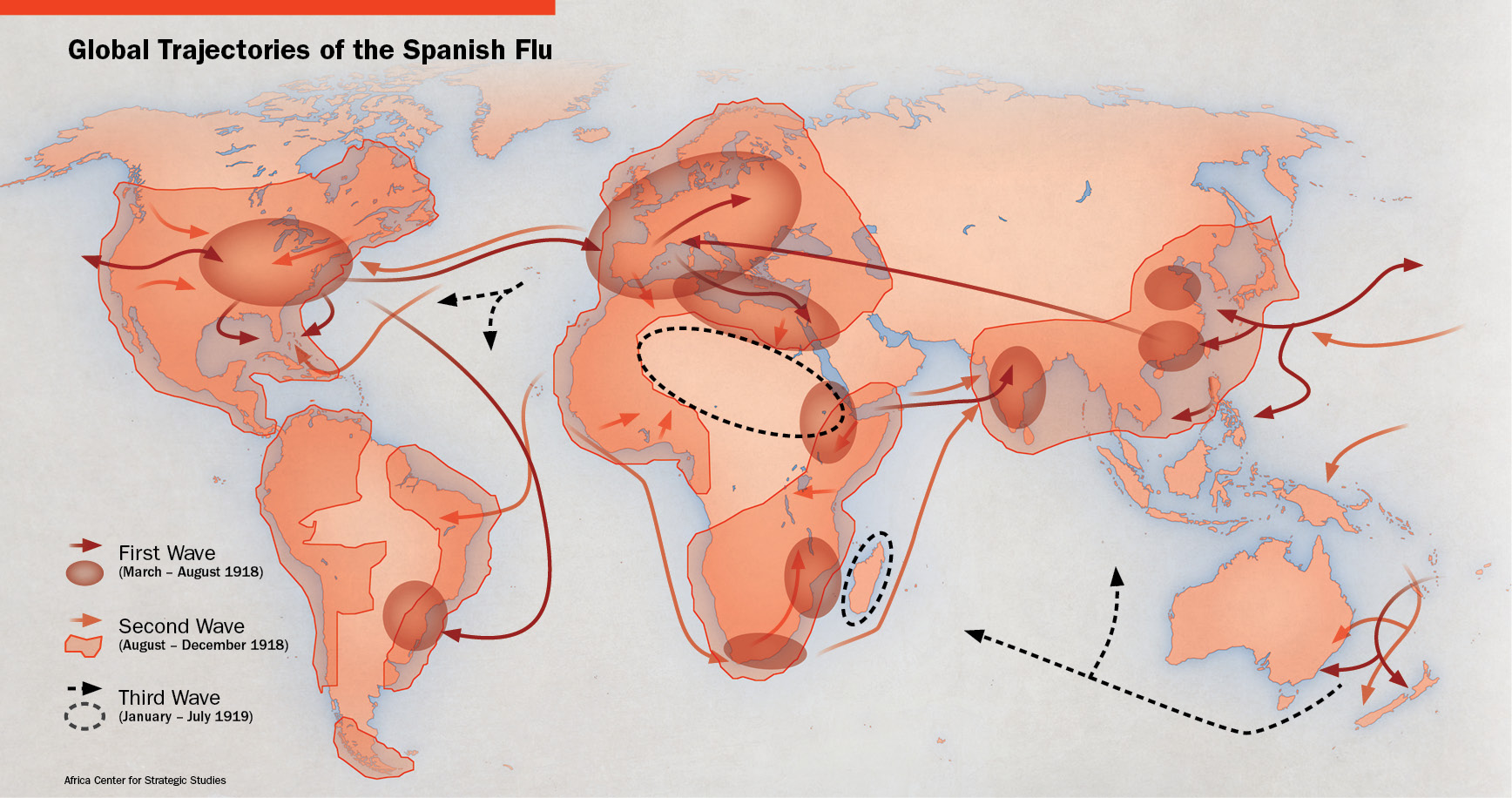

The tendrils of the world’s “Great War” had spread out from Europe to involve nations across oceans and continents since it began in 1914. By the spring of 1918, the conflict was in its final stages. Even so, troop movements in and out of countries and continents continued on a huge scale by ship and by rail. Scholars and experts agree that the troop movements gave rise to the influenza pandemic’s deadly global reach.

“World War I played a significant role in transmitting the virus rapidly and globally,” according to the May 2020 Africa Center for Strategic Studies (ACSS) paper, “Lessons from the 1918-1919 Spanish Flu Pandemic in Africa.” “Ships transporting some of the 150,000 African troops and 1.4 million laborers providing logistics support to the war in Europe brought the Spanish flu to the seaports of Freetown, Cape Town, and Mombasa.”

The Sierra Leonean, South African and Kenyan ports still are major regional economic drivers today. Their importance a century ago to a continent under colonial control cannot be overstated. Each was part of a vast and far-reaching colonial infrastructure that made ingress and egress to the continent’s interior simple. Ships went to those ports tightly packed with men fresh from the infectious soil of Europe. Upon disembarking, most boarded train cars to travel deeper into the heart of Sub-Saharan Africa.

The Sierra Leonean, South African and Kenyan ports still are major regional economic drivers today. Their importance a century ago to a continent under colonial control cannot be overstated. Each was part of a vast and far-reaching colonial infrastructure that made ingress and egress to the continent’s interior simple. Ships went to those ports tightly packed with men fresh from the infectious soil of Europe. Upon disembarking, most boarded train cars to travel deeper into the heart of Sub-Saharan Africa.

With their every breath, cough, handshake and embrace, they unleashed the potential for death.

It’s easy to underestimate the power of influenza. Its seasonal resurrection and spread often present newly mutated strains that can bedevil even those who have fought off flu multiple times. Vaccines are available, but none is foolproof. Influenza can cause mild to severe symptoms, from fever and malaise to debilitating pneumonia and respiratory distress. It sickens 3 million to 5 million globally each year, killing between 290,000 and 650,000 through respiratory symptoms, according to the World Health Organization.

There was something different, though, about the 1918 flu.

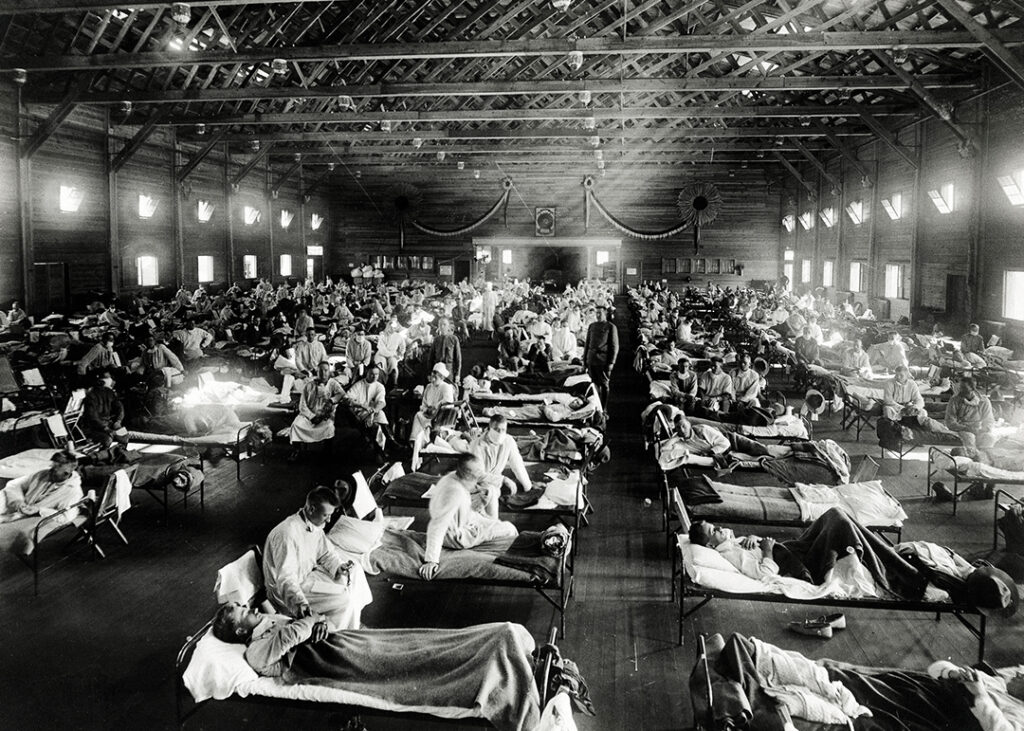

An African Killing Ground

The Spanish flu’s worldwide death toll has not been matched in the years since, and it was especially lethal in Africa.

Spanish flu infected half a billion people and killed between 20 million and 50 million. With a global population then thought to be about 1.8 billion, that marks a potential worldwide infection rate of up to 28% and a death rate of up to 2.8%. Some estimates put the global death toll at 100 million people.

Africa bore the brunt. “Nearly 2 percent of Africa’s population is estimated to have died within 6 months — 2.5 million out of an estimated 130 million,” the ACSS paper said. “The Spanish flu tore through communities, in some cases infecting up to 90 percent of the population and generating mortality rates of 15 percent.”

South Africa was one of the five-worst-hit nations on Earth, the ACSS stated. The flu also killed 4% of Freetown, Sierra Leone’s, population in three weeks. Across the continent, up to 6% of Kenya’s population perished within nine months.

Spanish flu was known for being a disease of the young. At its worst, it quickly overwhelmed the infected, causing their bodies to unleash fierce immune reactions that caused quick deaths. Historical anecdotes tell of people who went to bed well, woke up sick and were dead by nightfall.

COVID-19, in contrast, appears to be more dangerous for older people and those with underlying medical conditions. This is notable for a continent in which the median age is just under 20 years old.

The Flu Came In Waves

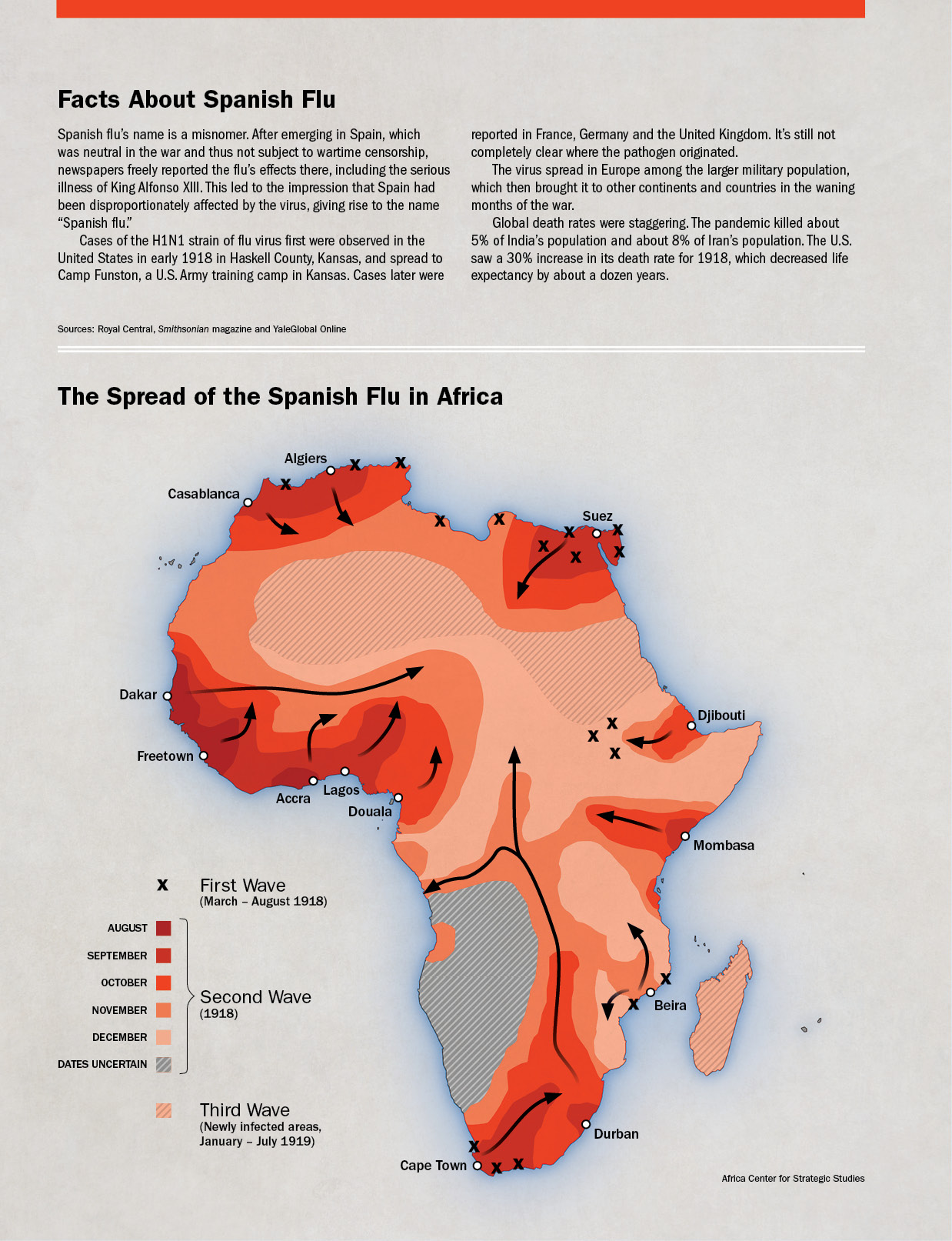

The Spanish flu came in three distinct waves. The first hit Africa in the spring of 1918 and lasted through most of the summer. This wave largely spared Sub-Saharan Africa, but it did lead to cases in North Africa, Ethiopia, and parts of East Africa and South Africa.

Then something happened.

As the virus roiled Europe during the waning months of the war, mutations transformed the strain into a deadlier pathogen.

“In late August 1918, military ships departed the English port city of Plymouth carrying troops unknowingly infected with this new, far deadlier strain of Spanish flu,” said an article by Dave Roos on History.com. “As these ships arrived in cities like Brest in France, Boston in the United States and Freetown in west Africa, the second wave of the global pandemic began.”

It was this second wave that devastated African populations. Because the initial wave did not penetrate the continent’s interior, vast Sub-Saharan populations were left without a whit of immunity to the coming onslaught. It was at this time that the three seaports played host to war returnees, and with them, the deadly flu.

A British Royal Navy warship carrying 124 sick crewmen docked in Freetown on August 14, 1918, without a proper quarantine, wrote South African historian Howard Phillips for 1914-1918-online: International Encyclopedia of the First World War. Men traipsed aboard with new loads of coal, and doctors and medics from other ships boarded to assist with those in the sick bay. Within two weeks, Phillips wrote, 70% of Freetown’s population had fallen ill.

Freetown’s infection spread south when two ships carrying South African Native Labour Corps troops home from Europe stopped at the West African port for coal. Soon after the ships left, sickness spread onboard. Cape Town authorities hospitalized the sick and sent the other Soldiers to camp for two days, where they were loosely quarantined, Phillips wrote.

“When none showed symptoms of influenza, they were formally demobilized and allowed to embark on trains for their homes all over the country,” Phillips wrote. “The next day, cases of ‘Spanish’ influenza appeared among the staff of the military camp and the transport unit that had conveyed the troops there, among the hospital staff, and among stevedores and fishermen working in the harbor.”

An Indian ship at the third major port, in Mombasa, is thought to have brought the second wave of flu into East Africa.

Soon, demobilized Soldiers, porters, colliers, railway workers, migrants toiling at mines and others began to disperse in hopes of escaping infected workplaces and villages — what Phillips called “the ubiquity of flu-infected men on the move.”

“Thus did the influenza virus spread, to a greater or lesser extent, throughout sub-Saharan Africa in the last quarter of 1918,” Phillips wrote. “From these three ports — which had become veritable nodes of infection for the continent — the pandemic spread along the coast and far inland, engulfing community after community.”

Just as the deadly second wave began to abate in December, a more moderate third wave arrived. It persisted into the summer of 1919.

However, Mari Webel and Megan Culler Freeman of the University of Pittsburgh caution against ascribing wave-like resurgences to the current COVID-19 pandemic. In an article republished by Smithsonian.com, the two researchers said that differences rooted in the biology of the two viruses make COVID-19 less likely to adhere to influenza’s wave behavior.

Simply put, coronaviruses tend to replicate more efficiently than influenza viruses, decreasing the number of mutations that can lead to seasonal changes. It is precisely because flus do mutate more easily and frequently that people are advised to get flu vaccinations each year.

Simply put, coronaviruses tend to replicate more efficiently than influenza viruses, decreasing the number of mutations that can lead to seasonal changes. It is precisely because flus do mutate more easily and frequently that people are advised to get flu vaccinations each year.

Influenza also tends to arise most often in colder weather, corresponding to winter. COVID-19 already has spread effectively in warm, temperate and colder climates.

“All this means that oscillations in COVID-19 cases are unlikely to come with the predictability that discussions of influenza ‘waves’ in 1918-19 might suggest,” Webel and Freeman wrote. “Rather, as SARS-CoV-2 continues to circulate in nonimmune populations globally, physical distancing and mask-wearing will keep its spread in check and, ideally, keep infection and death rates steady.”

Modern Lessons From the 1918 Flu

Although the two viruses are biologically distinct, influenza and COVID-19 are similar enough that the same mitigation precautions are effective for both. The ACSS highlights some areas that will require special attention as the COVID-19 fight continues.

Promote social distancing and sanitation: Fever, malaise, cough, headache, sore throat and respiratory difficulty all are shared between the two viruses. For that reason alone, people would be well-advised to maintain good personal hygiene with frequent hand-washing, social distancing and mask-wearing, and isolate when feeling sick.

During the 1918 pandemic, closings and bans on large gatherings helped slow the flu’s spread. Zanzibar, an archipelago that is now part of Tanzania, and Nyasaland, a former British protectorate now known as Malawi, were known for quarantines and contact tracing. “The efforts of these two governments were heralded as some of the most comprehensive on the continent,” according to the ACSS paper.

Monitor food security: Multiple reports show that food prices have skyrocketed across Africa during the current pandemic. A September 2020 report in The Guardian noted that staple food prices had jumped 50% in Sudan due to COVID-19 and other factors. Lockdowns, distancing, weather and existing conflicts all have led to food insecurity. The Famine Early Warning Systems Network shows that some of the most intractable problems are in South Sudan.

Leaders will have to monitor food chains and incentivize farmers while guaranteeing their access to transportation, storage and food processing. Households will need enough money to shop in local markets.

Build communication and trust: When diseases are spreading, whether they be Ebola or COVID-19, authorities must work to build trust within communities to gain access to treat, vaccinate and educate populations about public health. The West African and Congolese Ebola outbreaks underscored the importance of this, and it will be vital going forward as the COVID-19 pandemic continues and new vaccines are used.

Authorities in 1918 used radio and telegraphs effectively to inform medical authorities about incoming ships carrying Spanish flu as well as villagers about medical treatment opportunities.

Protect health professionals: Many parts of Africa already have few doctors and nurses to cover large populations. As COVID-19 spreads, facilities and the professionals who staff them must be protected. Some countries such as Kenya, Lesotho, Malawi and Sudan are mobilizing military and security forces to support and protect health professionals. This is one of the most important things that security forces can do during a disease outbreak.

No one can reliably predict when the COVID-19 pandemic will pass, but dealing with it effectively — however long it may last — will require vigilance, cooperation and a commitment to transparency, security and good governance.