ADF STAFF

John Momo is a 27-year-old seventh-grade dropout struggling with drug addiction in the notorious Zimbabwe ghetto in Paynesville, Liberia, where he has lived for nine years.

Hundreds of young people — men and women, boys and girls — come and go from one broken building to another. Trash is strewn about the dusty dirt floors, the smell of marijuana thick in the air. Living in squalor, the young people say they have little to do.

“Life here is bad,” Momo told Liberian newspaper Front Page Africa. “We are here smoking drugs. Nobody is coming to help us. We [do] not understand anything for our life here. It’s difficult for everybody in this building.”

In a country where civil wars raged from 1989 to 2003 and where depression and post-traumatic stress disorders often are untreated, illegal drugs have been a scourge for years. But a number of former child soldiers are determined to fight back by sharing their stories of addiction and rehabilitation while helping young people find treatment.

The United Nations Population Fund’s Liberia office estimates one in five young people uses narcotics. Many live in impoverished neighborhoods in Liberia’s capital, Monrovia, which also is home to a charity called the Network For Empowerment & Progressive Initiatives (NEPI) that delivers cognitive behavioral therapy and other trauma therapies to at-risk youth.

NEPI counts some 500 former child soldiers among those who have completed its program. Today, some of them volunteer to help younger generations.

“Since the end of the civil war the issue of drugs started in the country,” NEPI program manager Thompson Borh told Voice of America. “At first it was actually being done by the warlords. They were giving [narcotics] to the fighters in order to get them brave on the front lines, because at that point they cannot be coming to their senses.

“Then after the war it became a major business now in Liberia.”

In its 2023 situation report, civil society organization the Global Action for Sustainable Development (GASD) estimated that there are 100,000 drug users in Monrovia alone.

Illicit drug use and trafficking have plagued West Africa since they expanded dramatically in the late 1950s and early 1960s.

The U.N. Office on Drugs and Crime’s 2023 report said Liberia is among several West African transit hubs for cocaine, heroin and marijuana coming from Latin American, South American and Asian countries and bound for Europe. Cocaine seizures in the Sahel region jumped from 13 kilograms per year in 2020 to 863 kilograms in 2022.

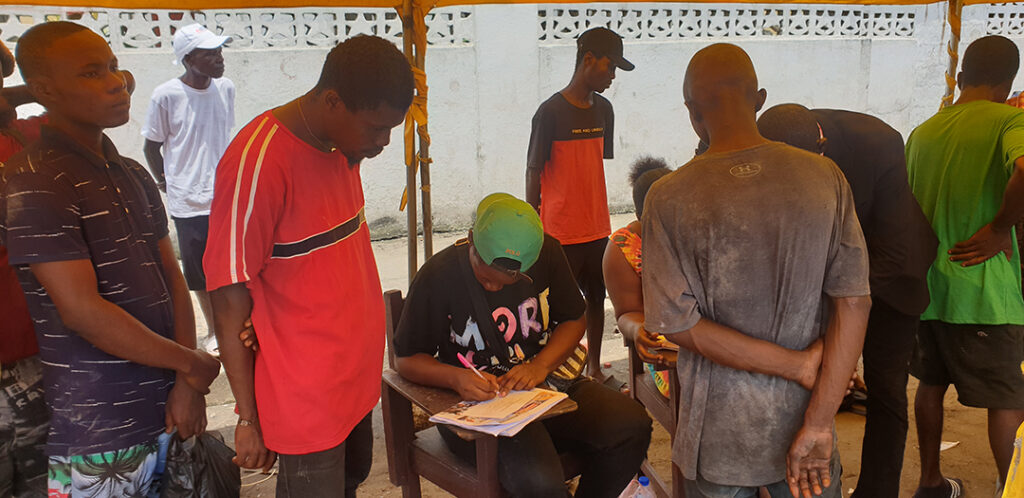

Substance abusers in NEPI’s eight-week program undergo one-on-one counseling, group sessions and life-skills training.

“There are some that carry weapons. Because of the abuse of drugs, they want to maintain that state and have become armed robbers,” Borh said. “We try to deal with those higher risks that are in the community.”

NEPI says it provides a $200 cash transfer for resettling when a participant graduates from the program. It’s part of a concerted effort to reintegrate drug users to society, NEPI chief trainer Johannson Dahn said.

“If they do not have somewhere good or safe to go, those are some of the things we get involved in,” he told VOA. “We find a family member and tell them about the importance of accepting them back in the home.”

NEPI graduated 314 participants from its cohort in August.

Illicit drug use and trafficking are behind Monrovia’s growing crime rate, according to local police and the Liberia Drug Enforcement Agency (LDEA).

LDEA Communications Director Michael Jipply said the agency doesn’t have the capacity to police all drugs coming into the country, noting its porous borders.

“There is limited capacity of security officers at the LDEA, in terms of the kind of equipment, devices, accessories we need to enhance our operations and also the issue of the limited manpower,” Jipply told Front Page Africa. “The numerical strength of the LDEA is not commensurate with our population.”

GASD pointed to a lack of sustainable drug prevention programs and warned of extreme consequences if the government fails to act.

“Liberia is losing a huge generation to drugs,” said GASD, which is based in Monrovia and Freeport, Sierra Leone. “If practical actions are not taken void of politics and donor-driven programs, we will inherit a situation more challenging than we ever imagine.”