ADF STAFF

The Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) recently declared an end to the Ebola outbreak in Equateur province, ending a monthslong effort to get it under control. Public health experts say the successful campaign offers insights into Africa’s upcoming effort to vaccinate hundreds of millions of people against COVID-19.

“I’m very optimistic,” Dr. Nicaise Ndembi, senior science advisor on vaccines for the Africa Centres for Disease Control and Prevention, told ADF. “But I’ll just point in the direction that Ebola was a small scale. This is different. This is unprecedented.”

He said the Ebola vaccination effort showed that such a huge undertaking is possible.

“Overcoming one of the world’s most dangerous pathogens in remote and hard-to-access communities demonstrates what is possible when science and solidarity come together,” Dr. Matshidiso Moeti, World Health Organization (WHO) regional director for Africa, said in a statement.

The Ebola effort overcame several major hurdles: Many of the affected areas could be reached only by air or water and had limited lines of communication. A strike by health workers also hampered the effort. Added to that, the Ebola vaccine had to remain extremely cold — a temperature of minus 80 Celsius — throughout the process.

Despite those challenges, medical personnel managed to vaccinate 40,000 people and halt the outbreak that began in June and killed 130 people. But COVID-19 will require vaccinating many times more people to reach effectiveness, a process that could take years.

Moeti said the same freezer technology that played a key role in the Ebola campaign also will make it possible to distribute a COVID-19 vaccine, particularly in rural areas with limited electricity.

Vaccines under development require temperatures as low as minus 80 Celsius for storage and transport.

“Traditional vaccines don’t require such cold,” Ndembi said.

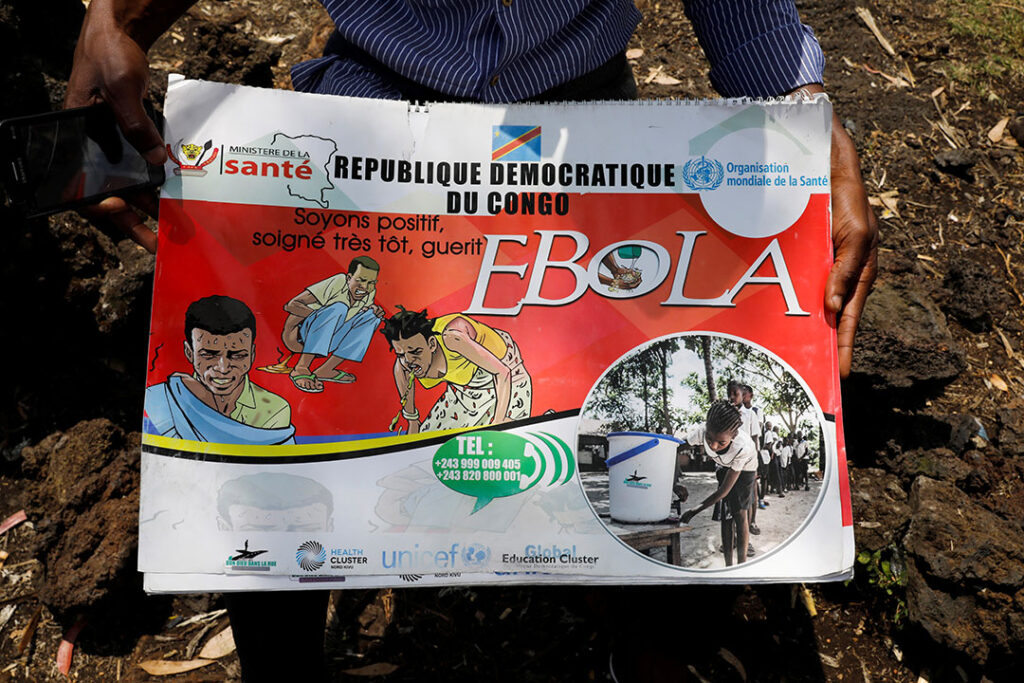

The other lesson from Ebola: Community outreach is vital to success.

The Ebola outbreak that struck West Africa from 2014 to 2016 created a stigma that caused people to avoid reporting cases and seeking treatment. Similar stigma has been connected to COVID-19 in some parts of Africa.

Ndembi said it will be important to understand what information people want about COVID-19 and then tailor public health messaging to break through barriers of misinformation and stigma.

DRC Health Minister Eteni Longondo said the Ebola campaign succeeded in part because the vaccines were readily available and technology allowed public health teams to move treatment centers within easy reach of effected communities.

Looking ahead to COVID-19, Ndembi said medical experts still are weighing their options for administering a vaccine.

“We might end up in a scenario where we have to choose whether to bring people to the vaccine or the vaccine to the people,” Ndembi said.