Crisis Management Training Can Help Organize Responses and Save Lives

ADF STAFF

As the moist kusi monsoon winds blew into Nairobi from the southeast in late April 2016, they brought with them the torrential downpours of Kenya’s rainy season. Kusi winds typically usher in the “long rains,” which stretch from late April through early June.

As rain fell for several days, flooding mixed with another of the Kenyan capital’s trouble spots: poorly constructed buildings. On April 29, a six-story apartment building near a river in the city’s poor Huruma neighborhood collapsed, bringing down tons of concrete on unsuspecting residents. Rescuers followed the faint voices of those trapped inside, pulling 140 people to safety. Forty-nine others died, Reuters reported on May 8.

A Kenya Red Cross spokeswoman told the Daily Mail the scene was “complete chaos.”

Kenya is not unique in East Africa or on the continent. Flooding is a perennial threat in the eastern, western and southern regions. Building collapses — often a result of shoddy construction — are common. East Africa also is prone to periods of extreme drought, which lead to famine, migration and tribal conflict. Fires are a threat, and pandemic diseases, including Ebola, have broken out in various regions through the years.

All such disasters require the same thing: a response. Ensuring well-coordinated and timely responses can save lives. U.S. Africa Command spent years working with disaster management officials in East Africa, particularly staffers at the International Peace Support Training Centre (IPSTC) in Karen, Kenya, to fashion a six-course curriculum on disaster management. The courses are delivered through the IPSTC’s Humanitarian Peace Support School in Embakasi.

All such disasters require the same thing: a response. Ensuring well-coordinated and timely responses can save lives. U.S. Africa Command spent years working with disaster management officials in East Africa, particularly staffers at the International Peace Support Training Centre (IPSTC) in Karen, Kenya, to fashion a six-course curriculum on disaster management. The courses are delivered through the IPSTC’s Humanitarian Peace Support School in Embakasi.

A July 2014 training-needs assessment focused on disaster management capacities in Kenya, Tanzania and Uganda. The study looked at 14 capacities and found several common themes:

- Often there is limited coordination between national governments and local communities.

- There are few trained disaster managers, and those duties typically are secondary to other duties.

- Officials lack resources, money and training for disaster management at the local level.

- Formal plans and procedures also are lacking at the local level.

- No local disaster managers had a “high capacity” in any assessment area. This underscores the need for training.

Those concerns have led to the formation of a disaster management curriculum that is bolstering knowledge and capacity among officials across East Africa.

AN ‘ALL-HAZARDS APPROACH’

Working with and through a regional training center was seen as the best way to build disaster management capacity, and the IPSTC already had a curriculum to build upon. Once training needs were identified, techniques were pulled together from a number of sources and redeveloped to match the IPSTC’s instructor-led delivery system.

AFP/GETTY IMAGES

This was done in two steps. First, a curriculum review board, composed of disaster managers and subject-matter experts, examined materials page by page, giving careful attention to language and cultural elements to determine what was best for East Africa. U.S. Africa Command and the IPSTC collaborated in that process.

Second, the center conducted a pilot program so instructors could check the curriculum over time while teaching the six courses. This allowed for feedback and adjustments along the way. Once officials completed the pilot, the six courses were handed over to the IPSTC in a February 2016 ceremony. Since then, the center has been delivering the courses on its own.

Crucial throughout this process was ensuring that the program embraced an “all-hazards approach.” The thinking is that although tailored to the sensibilities and needs of East Africa, the program should be useful and effective regardless of the disaster that arises, whether it be fire, flood or something else. This helps ensure sustainability.

Dr. Adane Tesfaye Lema, an agricultural entomologist from Ethiopia, helped review and develop courses, and served as a facilitator during the pilot period. Adane told ADF in an email interview that the pilot encouraged valuable knowledge, experience and information exchanges among the countries represented. It also encouraged the sharing of human and other resources among countries as well as multiagency planning.

IPSTC

Capacities to respond to natural and manmade disasters vary widely from country to country, and even from agency to agency within individual nations, Adane said. For that reason, training and information exchanges are crucial.

SIX COMPREHENSIVE COURSES

There are six core courses in the IPSTC’s disaster management curriculum. The incident command system (ICS) course teaches a standard on-scene organizational structure for disaster response. There are disaster preparedness planning and disaster management communications and early warning courses. The emergency operations center training course shows how to properly establish and operate a center.

The last two courses, taken together over two weeks, are disaster management exercise design and development and exercise delivery and evaluation. Both are presented as tabletop exercises to help participants test and validate disaster preparedness plans.

Kenya Defence Forces Maj. Luke Nandasava told ADF that several courses have been offered since the pilot program ended. He serves as lead facilitator and coordinates training with external stakeholders, such as foreign governments that sponsor training for African countries.

Nandasava said that, as of mid-July 2016, ICS had been offered four times during the year, serving 105 participants in all. The planning course had been offered once for 25 participants, and another was set for August with 40 participants. Nandasava said other modules were scheduled later in the year, and the intention was to offer all six courses at least once before the end of 2016.

A CUSTOMIZABLE CURRICULUM

All six courses in the program are intended for a wide audience of military and civilian officials alike. One of the strengths, Nandasava explained, is that the individual courses can be customized to fit more specialized needs. For example, in May 2016, Nandasava presented the emergency operations center module to Kenya’s Ministry of Tourism, customizing it to meet the ministry’s needs.

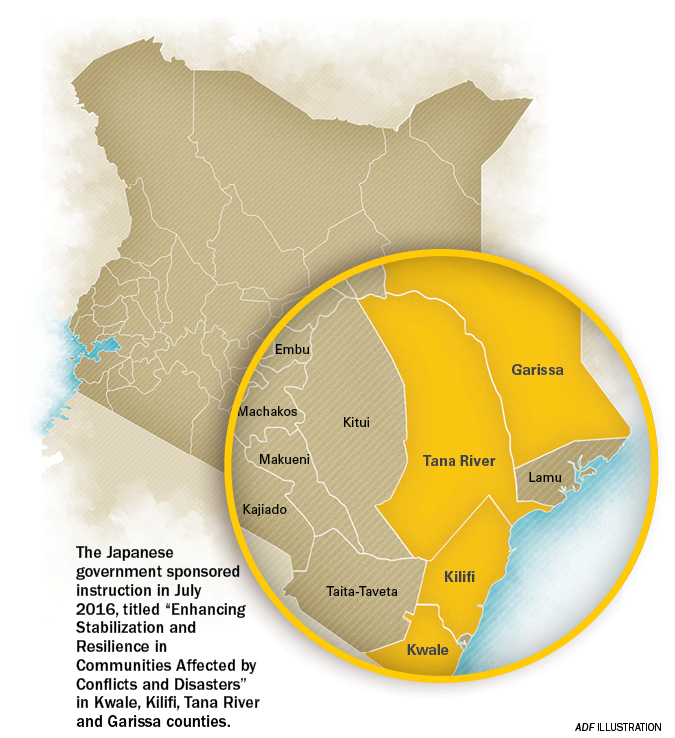

The courses also can be delivered on a more focused, local level. In July 2016, Nandasava led Japanese-sponsored instruction called “Enhancing Stabilization and Resilience in Communities Affected by Conflicts and Disasters” in Kenya’s Garissa, Kilifi, Kwale and Tana River counties. He has incorporated ICS and disaster preparedness planning into the instruction to help participants build capacity at the county level. Finally, he will help the counties develop exercises to validate their plans.

“So I’m actually using just the principles that we were taught from these six courses so that I can be able to customize them to fit the situation and … the scenario that I’m facing with the counties that I’m dealing with,” Nandasava said.

All four counties are in eastern Kenya, and Garissa borders Somalia. The instruction deals with disasters that emanate from terrorist incidents and mass casualties in the region. Garissa University College was the site of a horrific al-Shabaab terrorist attack in April 2015 that killed nearly 150 people and injured 79 others, mostly students.

The training is not likely to be limited to East Africa. Representatives from the Kofi Annan International Peacekeeping Training Centre in Accra, Ghana, have met with IPSTC leaders and have expressed interest in offering the program in West Africa.

REGIONAL SECURITY, CIVILIAN AUTHORITY

Initiatives such as the one the Japanese government is funding will help Kenya bolster its national security by spreading effective disaster response principles to the local level. Secure cities and counties contribute to secure nations. And secure nations help build regional security, which is an important goal of the program.

Every nation has its own capacity and way of doing business. With this training, however, standardized best practices can proliferate into countries across the region. This will make it easier for regional neighbors to cooperate if a particular incident requires it.

Nandasava said if a disaster involved Kenya and Uganda, for example, there could be “a unified command center close to where the incident has happened, but we have one incident commander from Kenya and another incident commander from Uganda who can be able to work together, agree on the objectives that they need to achieve, and also agree on the courses of action.”

Another component of effective disaster management, which the courses reinforce, is the importance of civilian authority over the military in disaster responses. Such matters have been a challenge in Kenya, Nandasava said. The ICS brings together all responders — police, the military and civilians — and lets them discuss and understand everyone’s responsibilities. Kenya also has a “mass casualty incident protocol,” which stipulates what agency should lead when a disaster strikes.

In Kenya, if an incident requires search and rescue, the Red Cross will take charge, Nandasava said. A Red Cross official will assign police and military forces to conduct operations. This negates any tendency by the military to take over, he said.

“And this has been informed from the incident that happened from the terrorist attack in Westgate, Nairobi, where we had a lot of issues in terms of coordination of security agencies,” Nandasava said. “But nowadays when an incident happens, we know that there will be a specific organization that will be in charge, and all other organizations that respond to that disaster will be able to report to that person.”

Nandasava said having the course principles and practices trickle down to the community level will be vital to addressing gaps in disaster management capacity moving forward.

“We are trying to sensitize people to understand that it’s not always to look at the military to provide solutions,” he said. “The military is only coming in as a support arm to that disaster, but those who are responsible for disaster response are actually the civilian and the police components.”