ADF STAFF

As debts mount in many African countries, civil society groups are calling for greater transparency so citizens can track exactly how public money is spent.

One example of this is Kenya, where authorities are refusing to reveal the conditions of the Chinese loan that funded the country’s $4.7 billion Standard Gauge Railway (SGR) between Mombasa and Naivasha. They say confidentiality clauses block them from making loan details public.

That answer was insufficient for civil society advocates Khelef Khalifa and Wanjiru Gikonyo, who sued the government to get access to all railway project documents through the country’s Access to Information Act.

“We have a right to know the details of the project: how our money is being spent, the consequences of a loan default, and the government’s decision-making process in signing the deal,” Khalifa said in a statement issued by Okoa Mombasa, a coalition of Mombasa workers, professionals and civil society groups.

The unprofitable SGR is Kenya’s largest infrastructure project and its greatest source of foreign debt. It’s also emblematic of the ways that Kenya and nearly two dozen other African countries remain mired in debt to Chinese lenders — debts often lacking transparency and that are difficult to repay or renegotiate.

That lack of transparency has made it difficult for international agencies to help nations restructure their debts because it’s impossible to know exactly how much they owe, according to a World Bank report. The agency says African countries will need to take on even more debt to rebuild their economies as they emerge from the pandemic.

“Declining revenues and wider public-sector deficits have increased the risk that unreported liabilities will emerge and make it difficult for these countries to service or restructure their debt,” the report said.

The economic strain created by the COVID-19 pandemic has made things worse, analysts say.

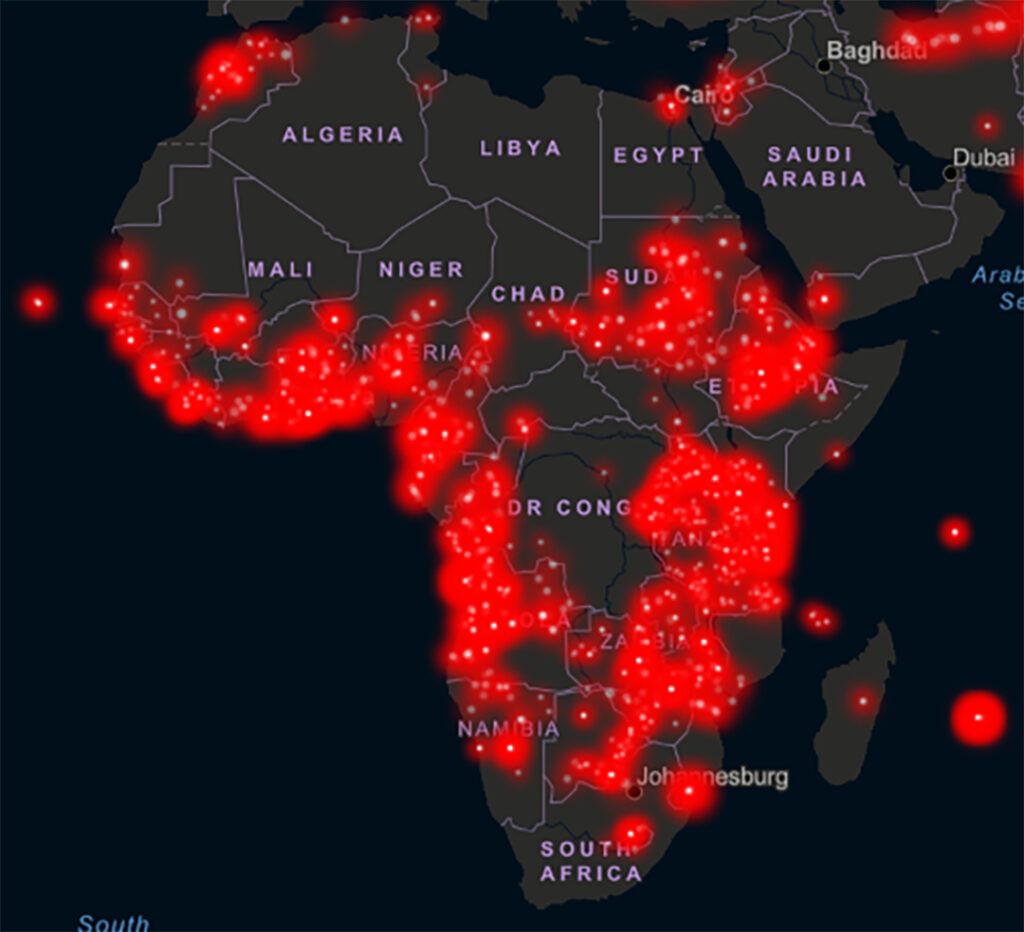

According to the International Monetary Fund (IMF), 20 low-income African countries were in financial distress in the second half of 2021, due largely to their debts to China. According to an analysis of World Bank data by the China Africa Research Initiative, China held 21% of African debt in 2021. Chinese loans accounted for 30% of African countries’ debt payments that year. Analysts say the secrecy surrounding Chinese loans means that percentage probably is much higher.

In some cases, those loans are designed to be repaid with commodities such as oil, bauxite or copper instead of cash. When commodity prices fall, as they did during the early period of the pandemic, countries find themselves without money to make their loan payments.

Since the launch of the Belt and Road Initiative, China has shifted away from lending to central governments and toward state-owned or state-backed enterprises. Those debts don’t show up on government balance sheets, even though governments often are responsible for them if the official borrower can’t pay.

“The ‘hidden debt’ problem is less about governments knowing that they will need to service undisclosed debts (with known monetary values) to China than it is about governments not knowing the monetary value of debts to China that they may or may not have to service in the future,” researchers with the AidData project said in an analysis of China’s lending to low- and middle-income countries around the world.

The struggle to repay Chinese loans raises the specter of a “debt trap” in which China could lay claim to ports, railways and other key pieces of African infrastructure to recoup its loans.

The G20 nations provided African countries with delayed repayment and other debt relief, as did the IMF and World Bank. Chinese lenders, however, refused to offer blanket relief, forcing borrowers to renegotiate their loans one by one.

The G20 ended its primary relief program, the Debt Service Suspension Initiative, last year and launched a new one called the Common Framework for Debt Treatments. China is part of that framework, which would apply to private lenders along with government and international funding.

So far only Chad, Ethiopia and Zambia have sought relief through the Common Framework, with each one experiencing “significant delays,” in the words of the IMF. Some of those delays are due to the complexity of setting up the Common Framework. Other delays are because of financial or political issues in those countries.

The IMF has called for suspending debt payments while the G20 finalizes the details of the Common Framework.

“We may see economic collapse in some countries unless G20 creditors agree to accelerate debt restructurings and suspend debt service while the restructurings are being negotiated,” the IMF wrote in a blog post. “It is also critical that private sector creditors implement debt relief on comparable terms.”

In the meantime, African countries continue to look for ways to manage their large debts to China.

In Uganda, for example, the Civil Aviation Authority (CAA) owes the China Eximbank $200 million for upgrades to Entebbe International Airport. Last October, lawmakers called on Finance Minister Matia Kasaija to explain the deal and the potential for China to lay claim to the airport should the CAA fail to keep up its payments.

“We shouldn’t have accepted some of the clauses,” Kasaija told lawmakers. “But they told you the price is either you take it or leave it.”

In the end, should the CAA fail to make its payments, the central government would be forced to step in and make them, Kasaija said.