COL. DANIEL HAMPTON AFRICA CENTER FOR STRATEGIC STUDIES

Hampton, a senior military advisor at the Africa Center for Strategic Studies (ACSS), has served 29 years with the United States Army as an infantry officer and foreign area officer, including as defense attache to Lesotho, Malawi, South Africa, Swaziland and Zimbabwe. This article has been adapted from a 2014 ACSS Africa Security Brief. It has been edited to fit this format.

A state maintains a military to defend its borders, deter aggression, and fight and win wars. These are missions normally associated with conventional forces. Yet, many states are now more likely to call upon their militaries to conduct peace-support operations than conventional combat. More than 100 countries provide uniformed personnel in support of 16 ongoing United Nations peace operations. More nations train, resource and equip their armed forces to achieve proficiency in the unique military skill set required for peacekeeping. This is particularly true in Africa. Not only do 78 percent of all U.N. peacekeepers serve in Africa, but nearly half of all uniformed peacekeepers are African. More than 70,000 uniformed personnel from 39 African countries serve in peace operations worldwide. Because most peace operations are in Africa, it is in African states’ regional security interests to participate, stabilize and help shape post-conflict environments.

Participation in a peacekeeping operation (PKO) also can augment resource-constrained defense budgets. When a troop-contributing country (TCC) deploys, the accompanying U.N. payment of per-Soldier stipends, combined with reimbursement for contingent-owned equipment, provides the TCC with significant finances. For example, the provision of a standard 800-person battalion to a U.N. PKO can mean up to $7 million for a TCC in the course of a six-month rotation. External actors (i.e., Western nations) perceive an advantage in offering training and equipment to African governments over deploying their own troops to a crisis area. Providing training and equipment is viewed as a relatively low-cost endeavor to address an emerging or existing security crisis, and it strengthens security cooperation relationships with African partners.

This intersection of mutually supporting interests has resulted in an abundance of programs, activities, exercises and events aimed at increasing African peacekeeping capacity. However, the tangible effects and long-term benefits of these efforts remain open to debate. Although it is true that capability is often created or enhanced to address specific crises or missions, sustained capacity and operational readiness are short-lived. This is evidenced by the recurring cycle of donor-led training programs and the frequent inability of the African Union to rapidly respond to emerging crises. An AU study of the 2012-2013 crisis in Mali lamented “Africa’s inability, despite its political commitment to Mali, to confront the emergency.”

THE CHALLENGE OF RETAINING READINESS

The standard model of donor peacekeeping assistance is often characterized as “train and equip.” Typically, an African military pulls together a composite trainee cohort, a group that may or may not be the actual troop contingent that will deploy in an operation. Instructors providing the training typically are Western Soldiers or, more often than not, private military contractors (PMCs). An equipment package is donated that may or may not be compatible with the host nation’s inventory, spare parts and maintenance systems. The model produces at best episodic and transitory proficiency.

The United States is the predominant donor nation. Through programs such as the African Crisis Response Initiative (ACRI), Africa Contingency Operations Training and Assistance (ACOTA), and the Global Peace Operations Initiative, the U.S. government has trained more than 250,000 African Soldiers in peace support operations at a cost of about $228 million per year.

This suggests that there are a quarter of a million well-trained African peacekeepers available for deployment. This is not the case. All military skills are inherently perishable. A trained peacekeeper in the past is not a trained peacekeeper in the present, nor does a trained peacekeeper in the present indicate an available trained peacekeeper for the future. Soldiers show marked degradation of task retention after 60 days. Without practice or retraining, after 180 days there is an estimated 60 percent loss in skill retention. With respect to collective task training (team training), the rate of degradation is even more rapid.

Cohesion of the collective is a recurring constraint to sustainable peacekeeping capability. With African peacekeeping contingents, frequently the unit receiving training is a formation cobbled together from multiple organizations and rounded out with individual Soldiers who have never previously trained together. In this scenario, upon completion of training the cohort disbands, with collective task proficiency essentially lost. In instances where the trained formation deploys directly into a peace support operation, proficiency is retained longer. However, upon completion of a normal six-month rotation, the formation no longer can be termed a trained peacekeeping asset if it does not retain cohesion and receive sustainment training.

Retaining post-deployment unit cohesion is difficult due to reassignment, promotion, retention and replenishment. Hence, the need for institutionalized training within an established professional military education (PME) system is important to sustained peacekeeping capability. Many African states lack an effective PME system to complement training received from international partners. The result is that acquired knowledge and experience erodes, capacity is not increased and capability is not retained.

Clearly, the key to retention of peacekeeping skills is an indigenous, institutionalized training. The United States’ ACOTA program acknowledges this tenet in its mission statement, yet to date there has been limited success in creating sustainable peacekeeping training institutions within Africa. At the inception of the ACRI program in 1997, there was a stated focus on “training the trainer.” However, such a methodology has never been fully implemented. When the ACRI program transitioned to ACOTA in 2002, the desire to build institutional capacity remained, but, in practice, the program continued to provide training primarily to African Soldiers rather than creating professional instructor cadres within African militaries. The trainers standing in front of the trainees still were predominantly American and almost exclusively PMCs.

Clearly, the key to retention of peacekeeping skills is an indigenous, institutionalized training. The United States’ ACOTA program acknowledges this tenet in its mission statement, yet to date there has been limited success in creating sustainable peacekeeping training institutions within Africa. At the inception of the ACRI program in 1997, there was a stated focus on “training the trainer.” However, such a methodology has never been fully implemented. When the ACRI program transitioned to ACOTA in 2002, the desire to build institutional capacity remained, but, in practice, the program continued to provide training primarily to African Soldiers rather than creating professional instructor cadres within African militaries. The trainers standing in front of the trainees still were predominantly American and almost exclusively PMCs.

In instances where a train-the-trainer approach has been applied, too frequently the African partner nation failed to use the trained instructors for their intended purpose, and many were reassigned or deployed shortly after donor-provided training. As more African states commit part of their defense force to peace operations, several have seen the utility in establishing dedicated peacekeeping training facilities. If an international partner is willing to provide instructors, training aids and resources for a specific training event or exercise, then there is not a perceived advantage for the host nation to incur the cost of staffing and operating a full-time training facility. Although this would seem to be pragmatic in a resource-constrained defense budget, it is a model that offers little in the way of institutional longevity. So peacekeeping training centers must be incorporated into a larger PME system. This will ensure sustained capacity and create economies of scale with respect to the cost of full-time instructor cadres and operating resources.

A NEW MODEL

Peacekeeping assistance must focus on building and supporting indigenous institutions in which a professional military instructor cadre trains the Soldiers that will comprise peacekeeping contingents. In this new model, peacekeeping tactics, techniques and procedures are embedded in doctrine and reinforced throughout all levels of a PME system. Lessons learned and operational experience are captured and incorporated into curricula and training exercises. The real metric of success is not how many people receive training, but how well a country sustains capability and maintains operational readiness to respond to an AU or U.N. request.

The days of Western Soldiers standing in front of African Soldiers as primary instructors should be long gone. In fact, several African militaries could accurately be characterized as professional peacekeepers with little need for outside training. Ghana, Rwanda, Senegal and South Africa have provided troop contingents to U.N. missions almost continuously for more than a decade. Incorporating these lessons, proficiencies and experiences into African PME systems is the key to sustainable capacity and capability.

Another advantage of removing the Western face from troop training is the opportunity to empower and legitimize host-nation noncommissioned officers. When a training instructor stands in front of a formed unit, there is an understood expert-to-novice relationship.

Training a cadre of professional instructors before a troop contingent exercise ensures that the recognized expert on the subject matter is not an American contractor but a noncommissioned officer from the responsible African force.

Emergent requirements to field-trained peacekeepers for missions in areas such as the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), Mali or Somalia will naturally shape the method employed. One cannot discount the short-term impact achieved via train-and-equip missions to prepare thousands of peacekeepers for deployment into crisis areas. However, at issue is the missed opportunity for long-term gains from the millions of dollars spent. If African and partner nations adopt and adhere to a policy of building institutional capacity, the demand for reactionary training diminishes as more TCCs sustain and maintain a higher level of operational readiness. The goal must be to create the conditions where train-and-equip missions are the exception, not the rule.

Several African U.N. TCCs — Nigeria and South Africa to name but two — have a dedicated peacekeeping training center and a fully developed PME system up through the defense college level. However, the link between operational experience and institutional education has not been optimized. Absent is a formal process and organization to capture lessons from the field, analyze them, and develop and adapt training curricula to sustain and improve performance and capability.

The International Peace Support Training Centre in Kenya and the Kofi Annan International Peacekeeping Training Centre in Ghana are examples that reflect successful partnerships between international actors and African states to create indigenous peacekeeping capacity. Although these centers are not designed to provide training for formed battalions, they are an excellent resource for sustainment training. They are primarily donor-funded, subregional assets that provide multinational classroom and seminar instruction at the operational and strategic level. These regional centers are not a substitute for institutional peacekeeping training capacity within a military’s PME system. However, they can be an effective complement to sustaining and maintaining critical peacekeeping skills.

SUSTAINING AFRICAN PEACEKEEPING CAPABILITY

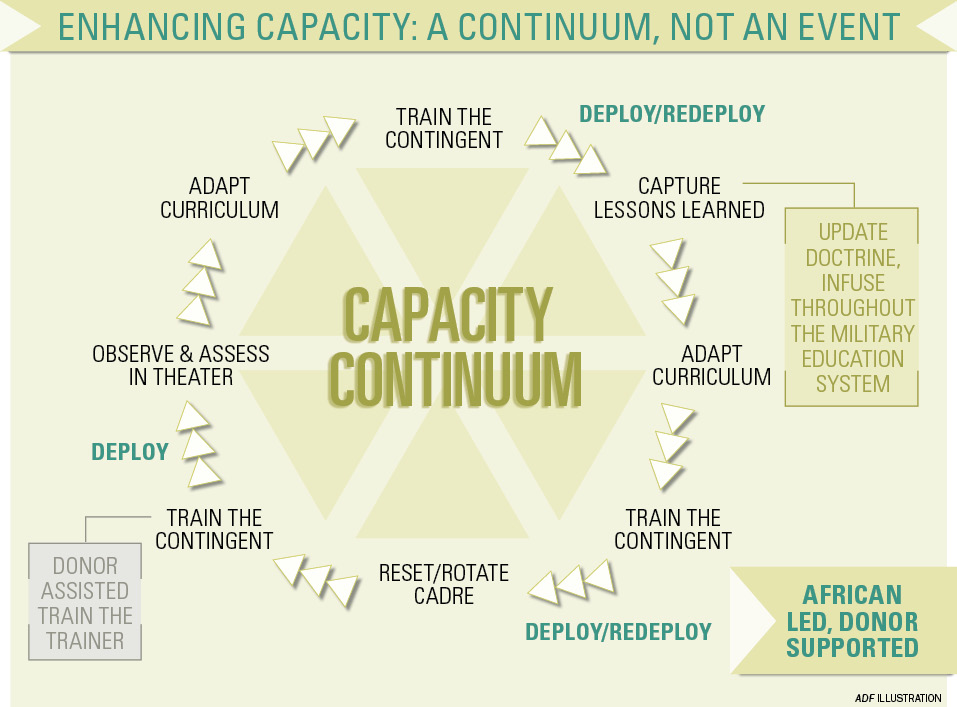

Enhancing capacity and capability is an ongoing effort, not an event. Achieving this will require changes from African governments and international partners. Both parties must ensure that resources and assistance are applied to the life cycle of a peacekeeping contingent to maximize retention of skill and experience for future units. This means that in addition to predeployment and post-deployment interaction, mentors should visit a unit in the theater to assess the suitability of the program of instruction and then modify it as necessary.

Donor programs designed to increase the capability of African peacekeepers require a collective approach. Assistance should be coordinated with other international and regional efforts. International assistance must begin with the baseline list of established U.N. and AU peacekeeping standards (the “United Nations Infantry Battalion Manual” is an excellent foundational document for the basic Soldier skills). From this baseline, a program of instruction can be adapted to the host nation’s tactics, techniques, procedures and experiences.

African policymakers also should selectively identify bilateral partnerships that can provide expertise or resources that transfer a unique or superior capability. Basic Soldier skills and traditional collective tasks associated with PKOs can be taught and proficiency achieved in a fairly straightforward and structured fashion. There are U.N.-approved programs of instruction available that any capable training cadre can adopt and apply. However, the more complex tasks and problem sets associated with peace support operations are not rote. For example, countering improvised explosive devices, explosive ordnance disposal, and intelligence surveillance and reconnaissance are capabilities the United States can offer to enhance African peacekeeping capability beyond basic Soldier skills. Although these skills were honed by the U.S. military during counterinsurgency operations, their application in the PKO environment is increasingly evident. More and more, the threats and situations faced by peacekeepers in the eastern DRC, Mali and Somalia are asymmetric in nature, involving nonstate actors possessing varying degrees of capability, equipment and technology.

Unfortunately, security assistance of this nature is too often lumped under counterterrorism programs. This is not only too limiting, but can evoke negative connotations. It is important to address the range of capabilities required in PKOs and avoid labeling certain military assistance and skill sets too narrowly.

When entering into military assistance partnerships, it is also worth examining the role of PMCs. There are several benefits for African and donor nations in using uniformed personnel rather than civilian contractors for PKO training. Although PMCs are fully capable and qualified to conduct most training to the same standards as uniformed military trainers, the issue returns to one of short-term versus long-term effects. The professional bonds formed during military-to-military interaction cannot be underestimated. At the Soldier level, the sharing of experiences and expertise during an exercise is mutually advantageous. Although there is a role for PMCs to play in augmenting a military lead during training events, the value of military-to-military interaction endures beyond training.

The cornerstone of sustainable peacekeeping capability is institutional training capacity. A generic peacekeeping training model in its simplest form is composed of three phases. In the first phase — train the trainer — international subject matter experts are used as needed to train a host-nation instructor cadre. In the second — train the peacekeepers — international trainers observe and mentor African instructors with little to no interaction with the trainees. The more challenging third phase — sustainment training — requires retention of an enduring professional cadre within the African defense force. This requires the will of senior defense and military leadership, and will often necessitate an organizational restructure within the force to create instructor billets that are permanent positions and considered career enhancing.

Ideally, a professional cadre of peacekeeping trainers would exist within a defense force’s PME system at a peacekeeping training school or center. Peacekeeping curricula should be incorporated throughout all professional development courses, such as platoon and company commander courses, staff colleges and warrant officer courses. Although this is an option for the more mature and better resourced defense forces, less endowed militaries can still institutionalize the training program without a designated facility or comprehensive PME system. A peacekeeping training cadre organized as a mobile training team can effectively prepare and train units to sustain capacity.

African states must better leverage donor assistance to increase and then maintain force readiness. African Soldiers are the best resource to train African Soldiers. African states must not let themselves become dependent on donor support to participate in U.N. or AU missions. It is in their interest to develop and sustain an indigenous capacity to generate ready peacekeepers. Likewise, donor nations must break from a seemingly perpetual cycle of training hundreds of thousands of African peacekeepers, frequently from the same handful of countries, with little sustained impact. The real shared interest of both parties is the establishment of sustainable peacekeeping capability that is institutionalized within African defense forces. It is time to move beyond the reactionary nature of train-and-equip missions and create enduring capacity.

Building Blocks for Sustained Capability

- Train the trainer: Build African noncommissioned officer capability.

- Train the contingent: Africans train Africans.

- Institutionalize: Dedicate a training facility or mobile training team concept.

- Retain expertise: Maintain a professional instructor cadre within the defense force.

- Sustain: Integrate instructor cadres and curricula within African PME systems.

- Adapt: Capture and analyze operational lessons and update training curricula.

- Optimize Resources: Coordinate donor support to ensure complementarity.