ADF STAFF

The Mitchells Plain neighborhood sits along the outskirts of Cape Town, South Africa, in a section called Cape Flats.

It is a part of the city known for its notorious street gangs, who violently clash with each other and terrorize the residents. The gangs sport flashy and colorful names such as the Hustlers, Rude Boys, Ghetto Kids and Spoilt Brats. The language of graffiti marks walls, shacks and homes.

The gangs’ dealings in drugs, weapons and the shellfish abalone led to deadly turf wars. In 2018, Cape Town saw more than 2,800 murders, a rate of about 66 slayings per 100,000 people, The New York Times reported in 2019.

Gang violence was so bad that in July 2019, President Cyril Ramaphosa called in Soldiers from Cape Town-based 9 SA Infantry Battalion to help police halt the bloodshed in Cape Flats neighborhoods, defenceWeb reported. After two months, Ramaphosa ordered a second deployment of 1,322 Soldiers as part of Operation Lockdown, which was extended through March 2020, just as the COVID-19 pandemic was spreading in Africa.

The military presence sought to bring calm to the townships in Cape Town, the Times reported, while helping schools and other public services to resume operations safely.

As the pandemic spread the new coronavirus across South Africa, life began to change in the townships — and with it, the behavior of its gang members.

COVID-19 changes crime

There are many types of organized crime in Africa: drug and human trafficking, weapons smuggling, extortion and petty rackets of all sizes. Many of those unlawful enterprises were stifled due to changes and restrictions arising out of lockdowns and travel patterns associated with COVID-19. But authorities are already seeing criminals adapt to the new normal.

“The locking down of public movement and the sealing of borders have had an immediate impact on some criminal activities, which have slowed or stopped,” according to the March 2020 report “Crime and Contagion: The impact of a pandemic on organized crime” published by the Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime. “But, equally, reports are already emerging of criminal groups who have exploited confusion and uncertainty to take advantage of new demand for illicit goods and services. Criminal opportunism will emerge further as the crisis unfolds.”

The Global Initiative paper argues that the pandemic is likely to affect organized crime in four major ways:

Social distancing, travel restrictions and other constraints have limited criminals’ ability to engage in certain acts. They can be expected to adjust to these constraints.

The pandemic has redirected the attention of law enforcement and politicians, which could allow criminals to increase or redirect their activity.

With the ever-increasing need for personal protective equipment (PPE) and other medical items, criminal organizations already at work in the health sector have new chances to exploit their positions.

Cyber crime is emerging as a domain for long-term criminal growth as other avenues for lawlessness have constricted or closed.

As criminals have changed tactics, law enforcement and security forces have had to adapt with them. Below are some examples of how each of these four categories have manifested themselves on the continent.

Criminals adjust to changes

In the Manenberg township of Cape Town — a city known for its proliferation of organized crime — 10 large gangs and about 40 small ones operate in the violent enclave, according to the Global Initiative’s website.

Two weeks after a nationwide lockdown, the gangs made temporary peace with one another and began handing out food packages to residents. But Global Initiative’s interviews with Manenberg residents and others indicated that gangsters sometimes embedded drugs and weapons in the food parcels. When the food wasn’t used as cover for contraband, it became a type of currency that gangsters used for support and to build indebtedness for recruitment.

“The very gangsters who now support NGOs [nongovernmental organizations] and religious bodies during the lockdown by distributing food parcels are the same gangsters who will hound those NGOs and religious leaders for a reference letter and to testify on their behalf when they [the gangsters] get on the wrong side of the law,” a senior police official in Cape Town told the Global Initiative.

“The very gangsters who now support NGOs [nongovernmental organizations] and religious bodies during the lockdown by distributing food parcels are the same gangsters who will hound those NGOs and religious leaders for a reference letter and to testify on their behalf when they [the gangsters] get on the wrong side of the law,” a senior police official in Cape Town told the Global Initiative.

Residents said they fear gang members will keep a tab on who they help and one day exact a return on their investment. “Today, they will give me a food parcel in front of my son, but a few months later they will remind him of the food parcel and tell him to deliver ‘goods’ for them,” a Manenberg resident said in April 2020. “This is going to come back to us.”

The focus of law enforcement

Vanda Felbab-Brown, a senior fellow with the Brookings Institution and an expert on security threats, wrote that the pandemic and related restrictions are likely to change the way law enforcement assets are used.

That probably will manifest itself in a transfer of law enforcement from rural areas to more urban settings, where populations are denser. This shift can leave rural communities “vulnerable to crimes of opportunity and crimes of desperation,” she wrote.

In Africa, this has led to an increase in poaching for personal subsistence and for international trafficking.

Conservation experts and park rangers told the BBC in a May 2020 report that the closing of the safari tourism industry has left thousands unemployed and many turning to poaching animals such as antelope for food.

“Since this pandemic of COVID-19, the threat has gone high in terms of people wanting to do poaching,” said John Tanui of the Lewa Wildlife Conservancy, a 250-square-kilometer park in Kenya where 100 scouts and rangers patrol. “Once these guys either they don’t have a job, they want an income, they may want to try other things like maybe poaching a rhino, poaching an elephant, and sell those trophies for their living.”

Charlie Mayhew, chief executive of Tusk, an organization that supports conservation in Africa, agrees. “This is definitely the biggest threat that we’ve seen to the conservation world. We are already beginning to see significant redundancies, job losses, across the whole of the tourism and conservation sector right across Africa,” Mayhew told the BBC. “So the big concern for us really is that this may drive an upsurge in poaching for bushmeat and snaring — hunting just to put food on the table.”

Some who are out of work may turn to selling wildlife parts on the illegal market. Global Conservation Force says many anti-poaching units are funded by money raised through safari lodging revenue. With tourism halted, the rangers often do not have the money to patrol game preserves. This gives free rein to poachers who traffic in rhino horn and ivory.

Other trafficking flows also are changing because of the pandemic. Ian Ralby, CEO of I.R. Consilium and a maritime expert, told ADF that gold coming out of the Democratic Republic of the Congo is moving by trucks instead of planes because of flight reductions. “The maritime space is absorbing some of what criminal goods would have flown before,” he added, saying that authorities should give shipping more scrutiny.

Medical needs present opportunities

As COVID-19 spread globally, so did the need for medical PPE, which includes face masks, face screens, gowns, sanitizers and medicines. Ralby told ADF that he has seen counterfeit PPE emerge as a criminal trend, with networks setting up to produce and distribute the items at exorbitant prices.

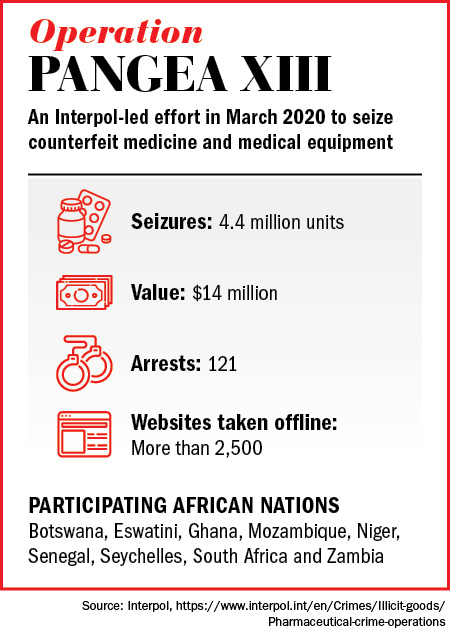

Criminals indeed wasted no time. Soon after COVID-19 began to spread across the globe, Interpol announced the results from Operation Pangea XIII, which ran March 3-10, 2020. The crackdown resulted in 121 arrests worldwide as police, customs and health regulators from 90 nations, including nine African nations, seized counterfeit face masks, bad hand sanitizers and unauthorized antiviral drugs, among other things.

In that one week, authorities inspected more than 326,000 packages and seized more than 48,000 of them, Interpol said. Pangea found 2,000 web links advertising COVID-19-related items. Authorities seized more than 34,000 bad masks, items such as “corona spray,” and other packages and medicines. Inspectors also seized unauthorized doses of chloroquine, an antimalarial medication once touted as a treatment for COVID-19.

“Once again, Operation Pangea shows that criminals will stop at nothing to make a profit,” said Jürgen Stock, Interpol’s secretary general. “The illicit trade in such counterfeit medical items during a public health crisis shows their total disregard for people’s well-being or their lives.”

“Once again, Operation Pangea shows that criminals will stop at nothing to make a profit,” said Jürgen Stock, Interpol’s secretary general. “The illicit trade in such counterfeit medical items during a public health crisis shows their total disregard for people’s well-being or their lives.”

Interpol reported that the operation shut down more than 2,500 websites, social media pages, online marketplaces and advertisements for illicit pharmaceuticals, and more were expected to be shuttered. The operation disrupted 37 organized crime groups.

Pandemic widens cyber crime arena

One of the social byproducts of COVID-19 is the proliferation of local and nationwide lockdowns and the call for social distancing. As a result, many businesses have closed or significantly altered their modes of commerce.

As fewer people congregate in public places, opportunities for street-level crime are likely to decrease in many places, wrote Felbab-Brown for the Brookings Institution. This can reduce crimes such as muggings because no one is on the streets, and burglaries may decrease because more people are at home.

However, with more people sheltering at home, the opportunity for internet-based crime increases. Homebound people are more likely to shop and conduct other activity online. In Africa, many people already conduct banking and money transfers using mobile phones.

The South African Banking Risk Information Centre (SABRIC), a nonprofit formed by major banks to help combat organized crime, indicated in March 2020 that criminals are exploiting the pandemic, according to a report at ITWeb, a South African business technology website.

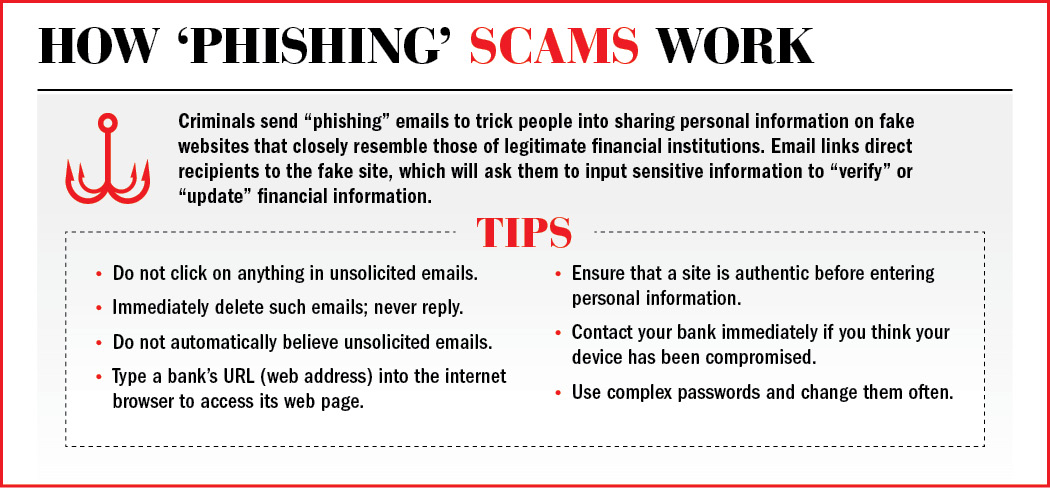

Criminals use bogus emails and text messages to fraudulently offer PPE, vaccines or other medical products by directing people to “phishing” websites. The emails often appear legitimate by using logos of reputable companies. Some phishing links seek to steal private bank information.

“Although some spoofed e-mails can be difficult to identify, we urge bank clients to think twice before clicking on any link, even if an email looks legitimate,” SABRIC acting CEO Susan Potgieter told ITWeb. “Any suspicious e-mails should not be opened and are best deleted.”

Opportunities to collaborate

Ralby told ADF that maritime authorities are seeing changes in the way criminals operate at sea. Oil prices, already trending low in the past few years, have been further degraded by falling demand as nations shut down and curtail travel worldwide. Because of this, oil theft — once pervasive in the Gulf of Guinea — has given way to the Somali style of piracy in West Africa that involves kidnapping for ransom.

Finding ways for maritime officials to continue cooperating, especially by harnessing low-cost technology, will be key moving forward, Ralby said. In the recent past, African authorities have spent hundreds of thousands of dollars to gather at large, regional meetings to discuss how they might better cooperate. Such efforts involve hotels, plane flights and venue expenses. In fact, officials from many policy and security arenas do the same.

Now the same officials can log onto Zoom or another online meeting platform and hold a meeting any time with no expenditures whatsoever. Those meetings can span oceans and continents, thus linking regions with shared interests in fighting global trafficking and other crimes.

Ralby said that in 2020 Gulf of Guinea officials conducted a number of webinars focused on maritime security during the COVID-19 pandemic.

“And importantly, it’s not external parties that are organizing these meetings,” he said. “It is African states, African NGOs, African governments getting themselves together to say, ‘Look, we’ve got a shared interest in this.’ That’s exciting.”